A recent study has decoded how Maya astronomers forecasted solar eclipses with astonishing accuracy more than a thousand years ago, revealing a sophisticated system of mathematics and observation that kept their predictions accurate for centuries.

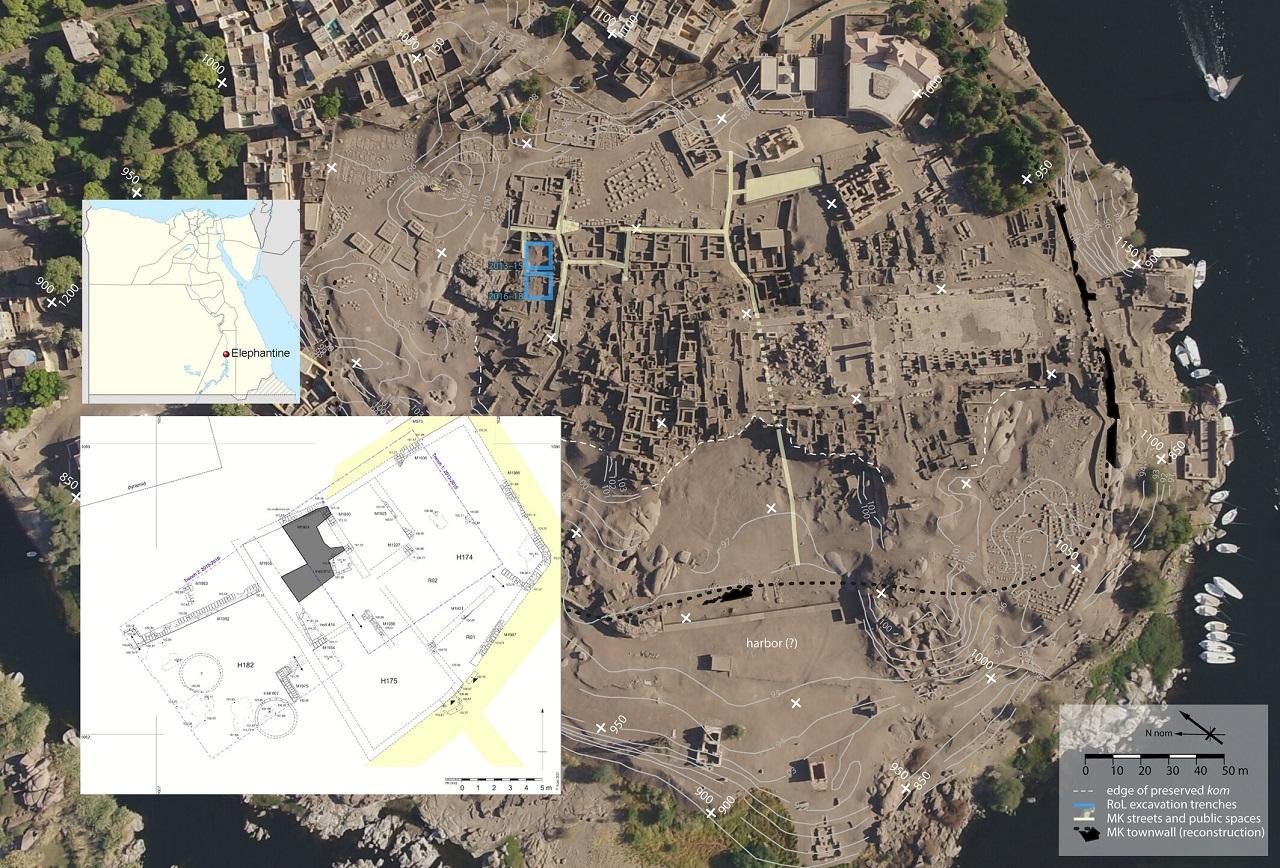

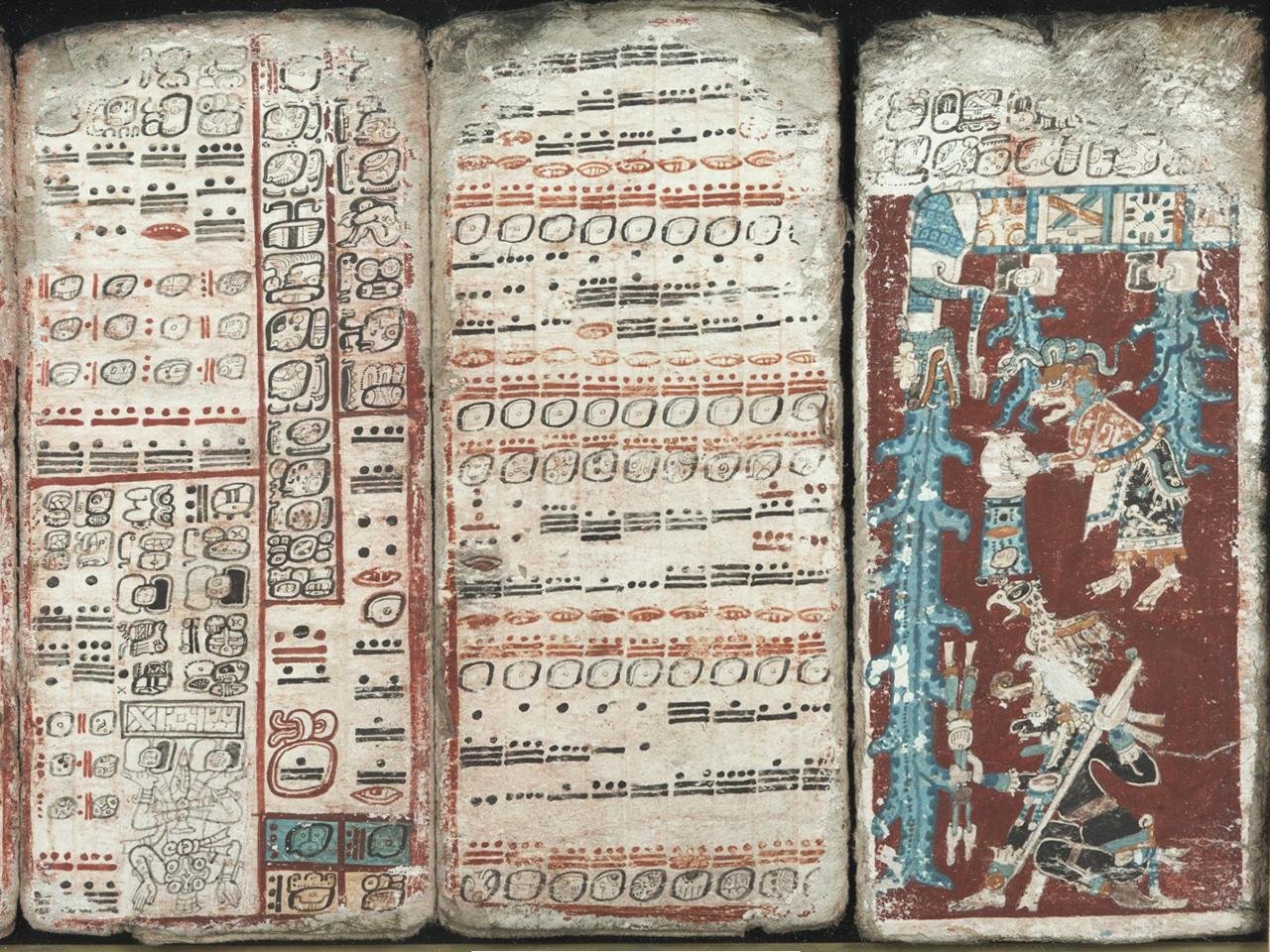

Sheets of the Dresden Codex depicting eclipses, multiplication tables, and the flood. Credit: Public Domain

Sheets of the Dresden Codex depicting eclipses, multiplication tables, and the flood. Credit: Public Domain

The research, published in Science Advances, examines the famous eclipse table of the Dresden Codex, a 12th-century CE Maya manuscript. The codex, one of the few pre-Columbian American books in existence, preserves the culmination of centuries of astronomical knowledge gathered by Maya daykeepers, priests, and scientists who watched the skies with unwavering dedication.

For decades, scholars had presumed the 405-month cycle in the codex was designed exclusively for eclipse prediction. The new study refutes that hypothesis. Scholars John Justeson and Justin Lowry found that the table was conceived as a lunar calendar, which was later adapted to track solar eclipses by aligning it with the Maya 260-day ritual calendar. That calendar, which was used for divination and prophecy, helped align celestial events with religious and social life.

Mathematical modeling revealed that the 11,960-day duration of the table (which equals 405 lunar months) exactly matches 46 cycles of the 260-day calendar. This synchronization enabled Maya astronomers to predict when eclipses would coincide with particular ritual dates, blending scientific observation and spiritual significance.

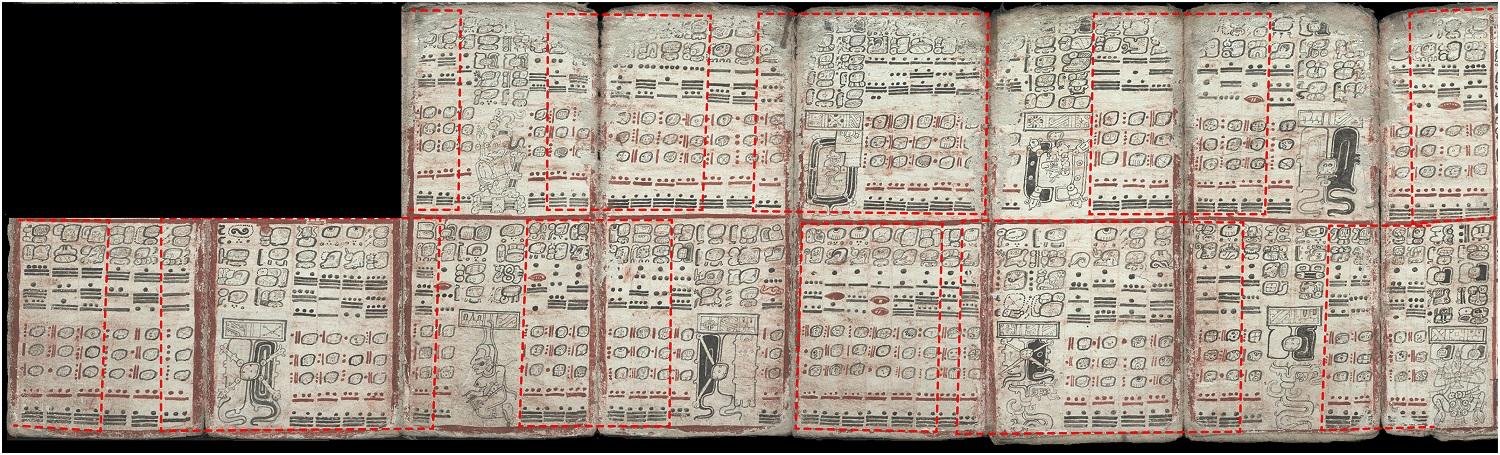

Eclipse table of the Dresden Codex. Credit: Justeson, J., & Lowry, J., Science Advances (2025)

Eclipse table of the Dresden Codex. Credit: Justeson, J., & Lowry, J., Science Advances (2025)

Each “station” in the eight-page eclipse table represents a new moon—potential moments when the Sun could be obscured. These are typically spaced six lunar months, or about 177 days, apart, which is the interval it takes for the Moon to return to the same alignment with Earth and the Sun. Keeping its accuracy over the centuries, however, was no simple task.

Earlier theories had ᴀssumed the Maya simply restarted the table when it ended, but the researchers discovered something far more precise. The Maya used overlapping cycles—resetting their tables at 223- or 358-lunar-month intervals, corresponding to the saros and inex eclipse cycles known today. The points of reset corrected tiny discrepancies that accumulated over time, allowing predictions to remain accurate for more than 700 years.

By combining four resets at 358 months for every one at 223, the Maya managed to calibrate their tables to anticipate every solar eclipse observable in their region between 350 and 1150 CE. When the researchers compared the information in the Dresden Codex with modern records of historical eclipses, the alignment was remarkably close.

To the Maya, an eclipse was not merely an astronomical event but a cosmic portent—a moment when the Sun’s light was devoured, signaling divine anger or renewal. Yet underlying these mythological explanations lay a foundation of data collection and mathematical reasoning that rivaled that of ancient Babylon or Greece.

The study concludes that the codex’s method, if continuously updated, would still be capable of predicting modern-day eclipses over Mexico today. This achievement, attained without telescopes or advanced instruments, is a testament to the Maya civilization’s intellectual depth.

More information: Justeson, J., & Lowry, J. (2025). The design and reconstructible history of the Mayan eclipse table of the Dresden Codex. Science Advances, 11(43), eadt9039. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adt9039