Researchers have long suspected that a ᴅᴇᴀᴅly epidemic compelled the sudden abandonment of Akhetaten, the short-lived capital built by Pharaoh Akhenaten. However, a new study by Dr. Gretchen Dabbs and Dr. Anna Stevens, published in the American Journal of Archaeology, challenges this ᴀssumption, suggesting that the city was never plagued.

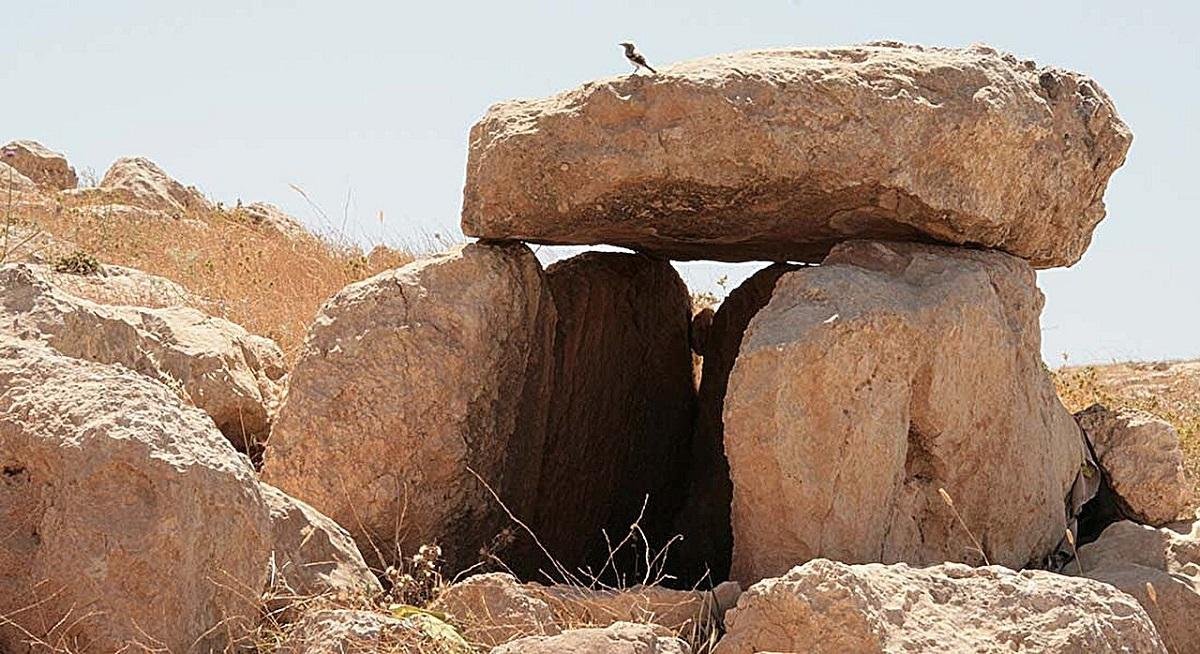

Ruins of the smaller Aten Temple at Amarna, located in the brief Egyptian capital, where archaeologists found no traces of the alleged plague. Source: Insтιтute for the Study of the Ancient World / CC BY 2.0

Ruins of the smaller Aten Temple at Amarna, located in the brief Egyptian capital, where archaeologists found no traces of the alleged plague. Source: Insтιтute for the Study of the Ancient World / CC BY 2.0

Akhetaten, today known as Amarna, was founded in the midst of Akhenaten’s radical religious reforms, when he promoted the worship of the sun god Aten over Egypt’s traditional pantheon. The city was largely abandoned within about 20 years, raising suspicions that disease had been the reason behind its people’s departure.

Much of this theory relies on external textual sources: Hitтιтe plague prayers mention an epidemic caused by Egyptian prisoners, and the Amarna Letters mention outbreaks in cities like Megiddo, Byblos, and Sumur. However, none of these texts mention Akhetaten itself.

To test the epidemic hypothesis, Dabbs and Stevens conducted a comprehensive bioarchaeological and archaeological analysis of Amarna and its cemeteries. Excavation work between 2005 and 2022 analyzed 889 burials in four large cemeteries, representing an estimated 11,350–12,950 total burials. The researchers compared patterns in burial practice, demography, and health indicators at Amarna with those found at known epidemic sites to identify evidence of crisis mortality.

Relief showing Akhenaten, Neferтιтi, and their children under the rays of the Aten, housed at the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. Credit: Lucas / CC BY 2.0

Relief showing Akhenaten, Neferтιтi, and their children under the rays of the Aten, housed at the Egyptian Museum in Berlin. Credit: Lucas / CC BY 2.0

The findings indicate that the skeletal remains predominantly reflect social and economic stress rather than disease. Stunted growth, spinal trauma, and joint degeneration were prevalent, while evidence for infectious disease was rare—only seven individuals showed signs of tuberculosis. Most of the burial contexts were orderly: the deceased were covered with textiles or placed in mat coffins and accompanied by grave goods, and no emergency interments were identified.

Whereas some communal burials occurred, demographic analysis reflected cultural patterns rather than epidemic response, such as the pairing of women and children. Paleodemographic modeling showed that death rates and life expectancy conformed with expectations for a city of Akhetaten’s size and 20-year occupation. Even the city itself shows evidence of gradual, systematic abandonment, with possessions collected and low-level occupation continuing after Akhenaten’s death.

Amarna necropolis, an ancient burial site. Credit: Olaf Tausch / CC BY 3.0

Amarna necropolis, an ancient burial site. Credit: Olaf Tausch / CC BY 3.0

Such evidence suggests that political and religious factors—instead of disease—were likely the cause of the city’s decline. The rapid desertion of Akhetaten is linked to a reaction against Akhenaten’s reforms and the restoration of traditional religious centers, not to an epidemic. Although Hitтιтe records may reflect an outbreak elsewhere, Amarna itself shows no archaeological or biological evidence of a plague.

More information: Dabbs, G. R., & Stevens, A. (2025). Mortality crisis at Akhetaten? Amarna and the bioarchaeology of the late Bronze Age Mediterranean epidemic. American Journal of Archaeology, 129(4), 455–489. doi:10.1086/736705