Archaeologists have uncovered the remains of a mᴀssive stone-lined basin in the ancient Roman city of Gabii, situated about eleven miles east of Rome. The structure, partially cut into the bedrock and dating to about 250 BCE, can be described as one of the earliest examples of Roman monumental architecture beyond temples and city walls. The discovery was made by a team led by Marcello Mogetta, a professor and chair of the Department of Classics, Archaeology, and Religion at the University of Missouri.

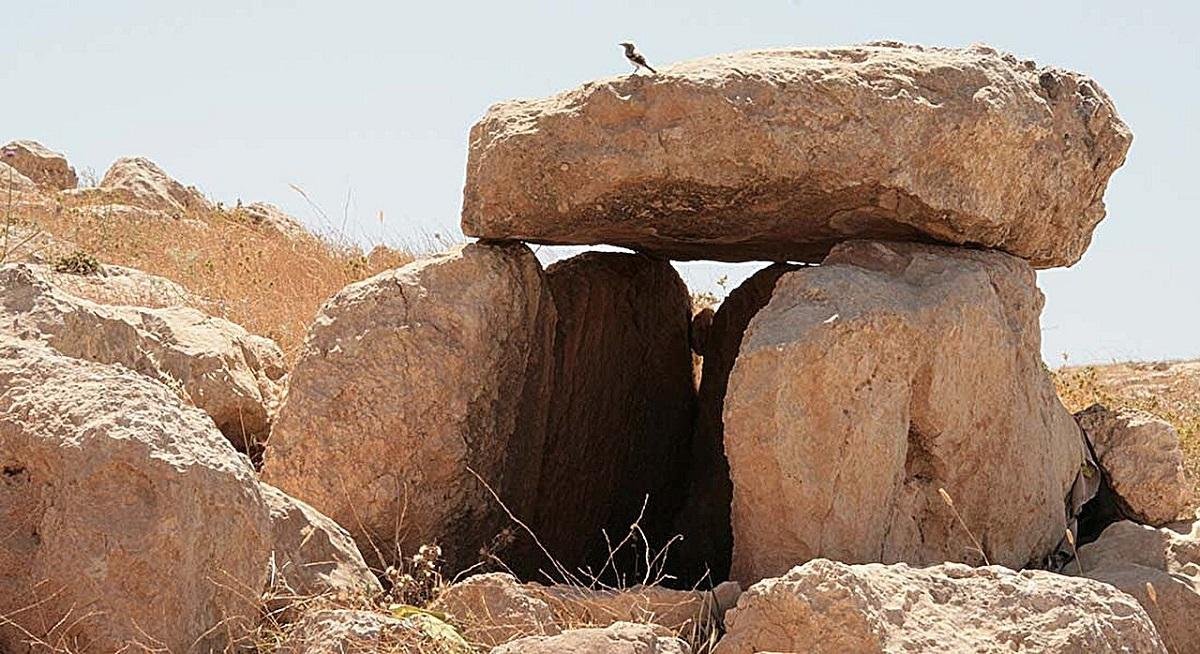

Archaeologists unearth mᴀssive ancient Roman basin in Gabii, Italy. Credit: Marcello Mogetta

Archaeologists unearth mᴀssive ancient Roman basin in Gabii, Italy. Credit: Marcello Mogetta

Researchers believe the basin served more than a practical purpose. Located near Gabii’s central crossroads, it was likely part of a monumental pool within the city’s forum—the civic and social heart of Roman urban life. Such an early example of a planned public space offers valuable insight into how the Romans began experimenting with urban design and monumental architecture as expressions of power and community idenтιтy.

Gabii’s remarkable preservation makes it an exceptional case for studying early Roman cities. Once a powerful rival to Rome, Gabii was largely abandoned by 50 BCE, leaving its original streets and buildings undisturbed beneath centuries of soil. Unlike Rome, where early layers are buried under later construction, Gabii provides a clear view of the city’s early structure and layout.

The basin adds to earlier discoveries by the same team, such as the “Area F Building,” a terraced complex carved into the slope of a volcanic crater around which the city developed. Collectively, these finds demonstrate how early Roman builders drew inspiration from Greek models, such as the Parthenon and the Agora—grand civic spaces that reflected both functionality and authority. The Romans extended these ideas to their own context, creating monumental landscapes that expressed political power as well as technical innovation.

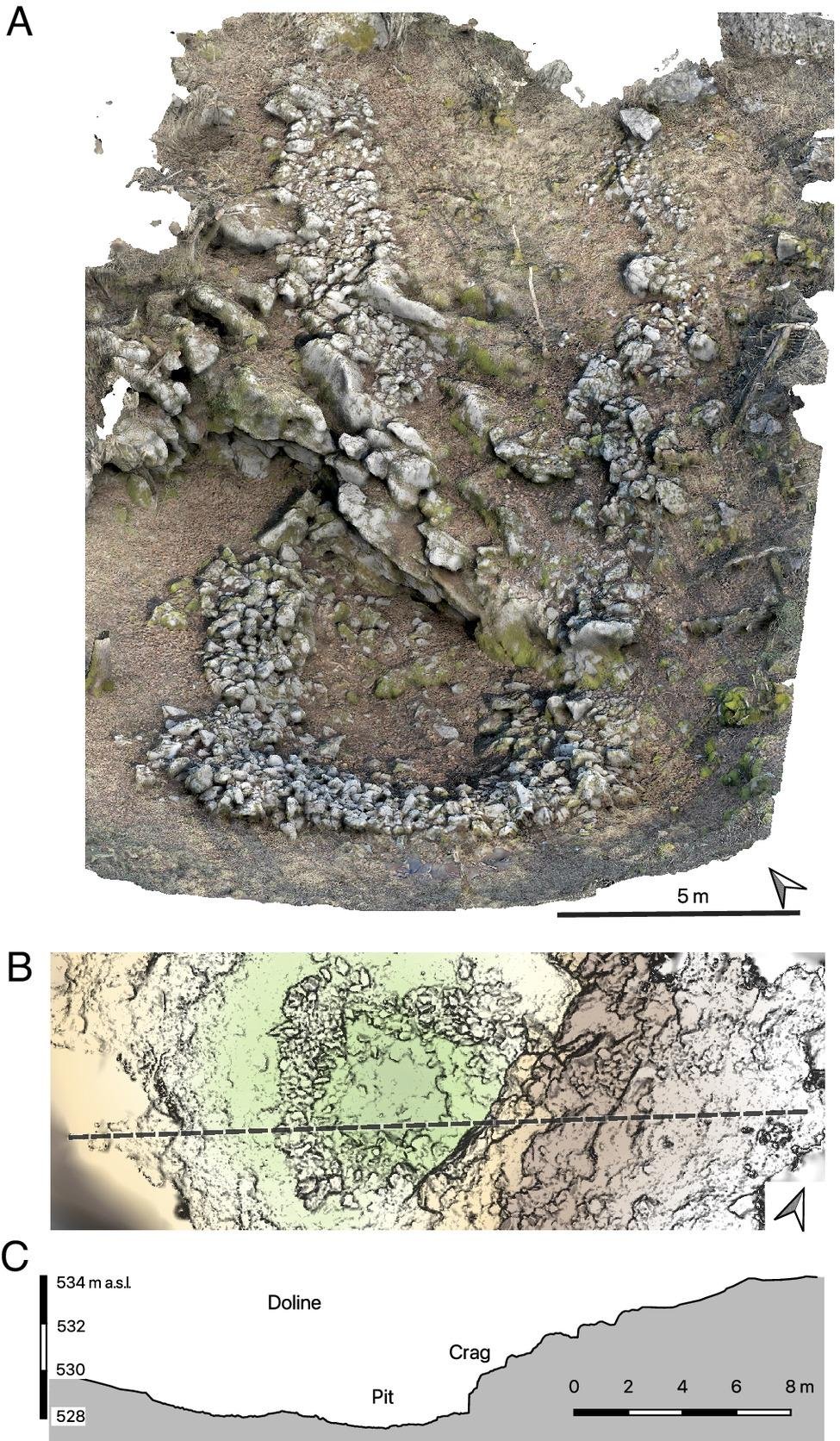

A 3D model of the ancient water basin. Credit: Marcello Mogetta

A 3D model of the ancient water basin. Credit: Marcello Mogetta

Since recognizing the cultural importance of the site, Italy’s Ministry of Culture has designated Gabii as an archaeological park, managed by the Musei e Parchi Archeologici di Praeneste e Gabii. This designation has resulted in continued excavation under the international Gabii Project, which Mogetta now leads. Supported by Italy’s General Directorate of Museums, the team plans to excavate material deposited within the basin and study the adjacent stone-paved area.

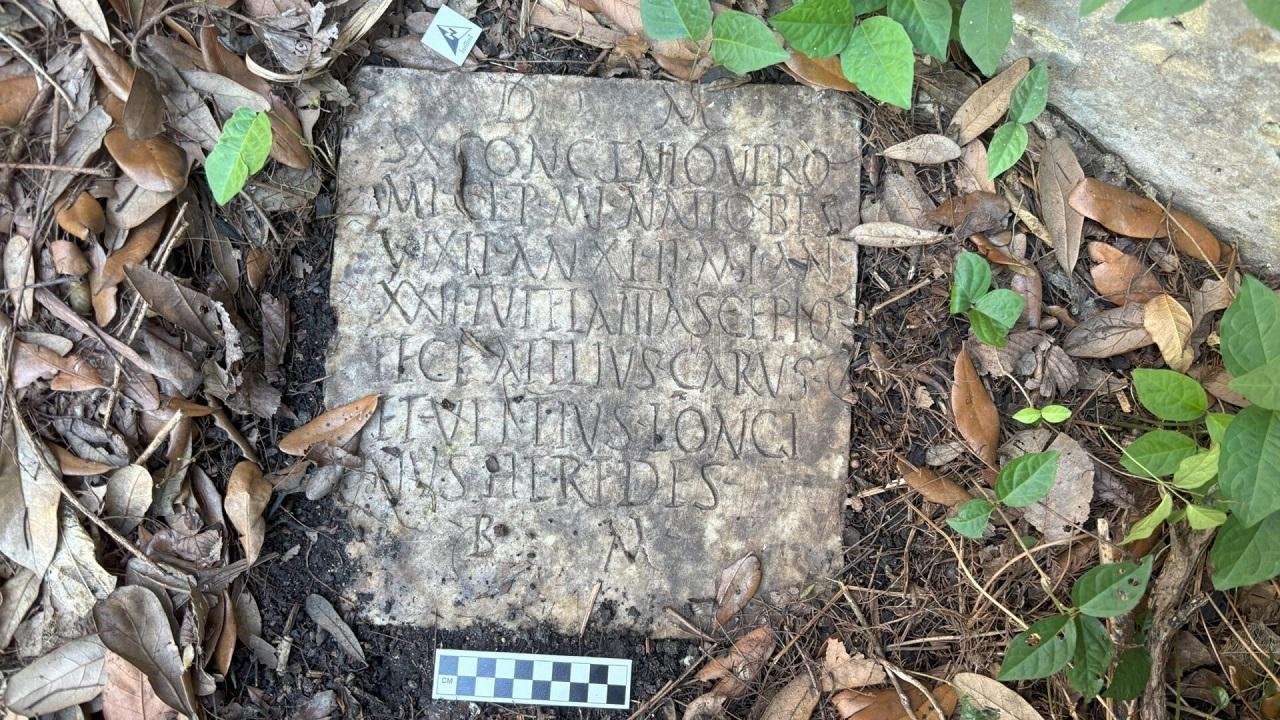

Archaeologists also intend to investigate a nearby “anomaly” detected by thermal imaging surveys. It may be a temple or another civic structure, possibly linked to the use and closure of the basin around 50 BCE. Some of the items recovered from the site include complete vessels, oil lamps, perfume containers, and cups with unusual markings. Some of these appear to have been placed there intentionally, perhaps as ritualistic offerings connected to the symbolic ᴀssociation with water.

The Gabii Project’s ongoing work is revealing how early Romans balanced religion, politics, and urban planning. One question still under debate is whether civic spaces developed before religious centers or the other way around. The answer could reshape how scholars understand the evolution of Roman cities and the role of monumental architecture in defining collective idenтιтy.

More information: University of Missouri