Archaeologists from the University of Copenhagen have uncovered a vast Early Bronze Age ritual landscape at Murayghat in central Jordan, offering fresh insights into how early communities responded to major social and environmental changes more than 5,000 years ago.

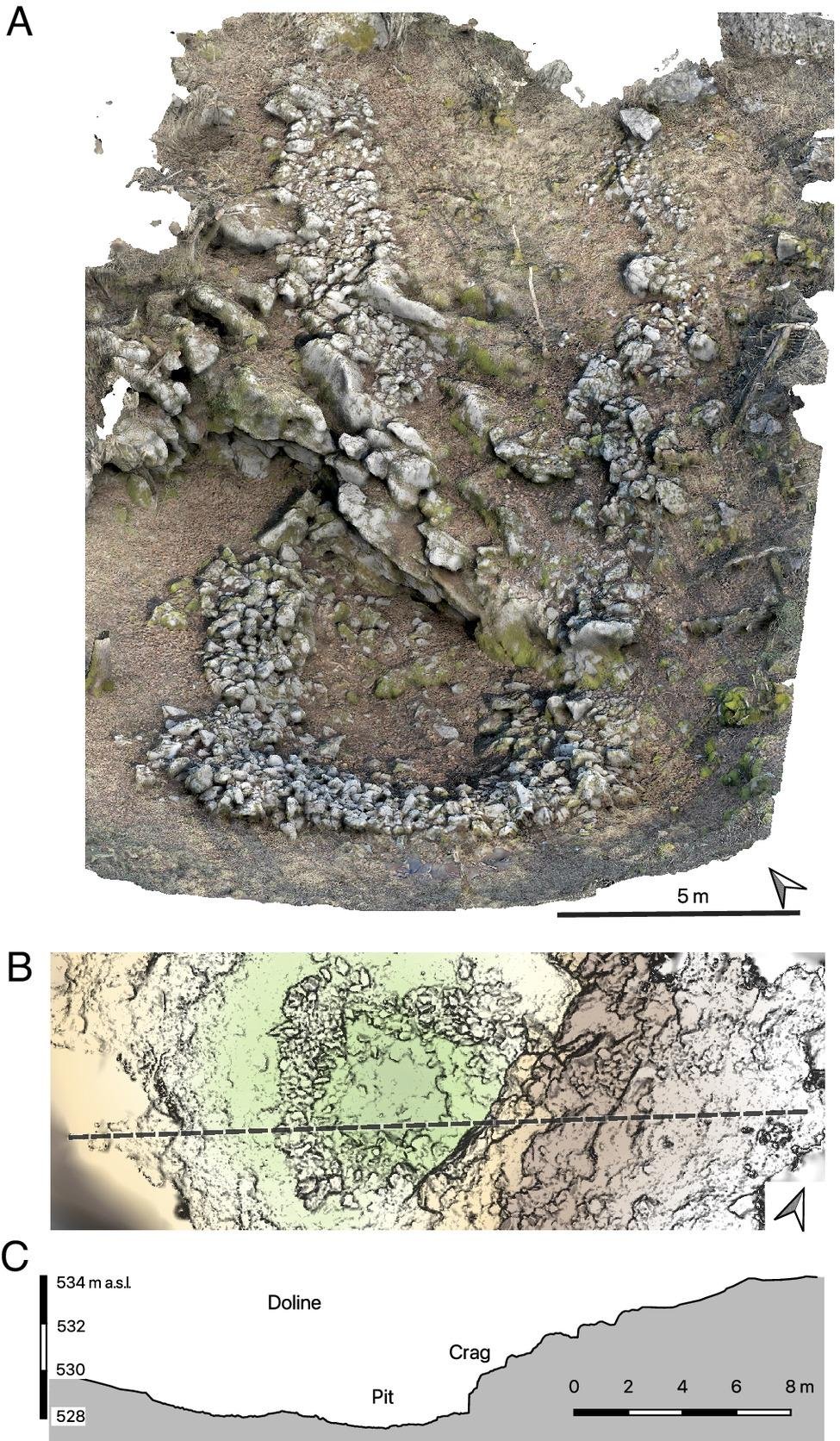

Dolmen found at Murayghat in Jordan. Credit: Susanne Kerner, University of Copenhagen

Dolmen found at Murayghat in Jordan. Credit: Susanne Kerner, University of Copenhagen

Located southwest of Madaba, Murayghat is dated to Early Bronze Age I (around 3500–3000 BCE), a period after the collapse of the Chalcolithic culture. The earlier era had been distinguished by established villages and elaborate symbolic traditions, but as it fell apart—likely due to climate shifts and breakdowns in trade and political systems—new forms of social organization began to emerge. Murayghat is one such transformations: a ceremonial complex built not for living, but for ritual and remembrance.

More than 95 dolmens—stone burial chambers—have been found spread out on the hills surrounding a central knoll. These are complemented by standing stones, cairns, and circular or oval enclosures that make up a distinctive ritual landscape. The majority of the dolmens are aligned to face the central hill, suggesting a deliberate arrangement for visibility and collective participation.

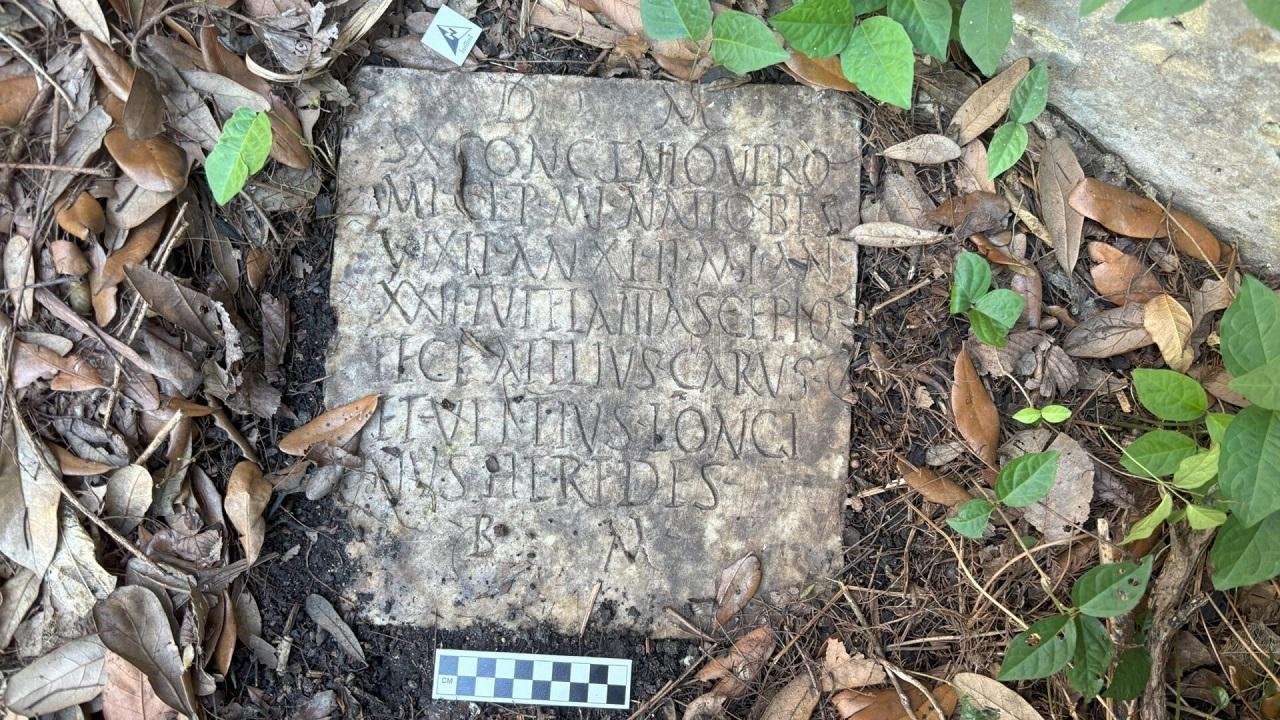

The dolmens range from two-meter-long chambers to over four meters in size, constructed of mᴀssive slabs of limestone and sometimes standing on built platforms. Human remains were absent from excavated examples, but their construction and clustering imply a highly commemorative purpose. Megalithic chambers, double-faced walls, and smoothed bedrock surfaces carved with cup-marks and rectangular depressions—presumably used for symbolic or ritual purposes and not for everyday life—were discovered by the archaeologists on the central knoll.

Artifacts found across the site validate this explanation. These include flint tools, basalt grinders, animal horn cores, and unusually large-sized pottery vessels—some of which are capable of holding up to 25 liters—suggesting communal feasting or offerings. The absence of hearths, roofing, and domestic debris indicates that Murayghat was not a settlement but a place where groups in the region gathered for ceremony and social engagement.

It is the broader context that accounts for the significance of the site. With the end of the Chalcolithic period, southern Levant communities experienced political fragmentation and environmental stress. In the absence of dominant central authorities, people turned to the construction of monuments as a means of maintaining unity and reaffirming shared idenтιтy. By marking the land with visible dolmens and standing stones, they created what scholars describe as an “anthropogenic landscape”—a human-built environment filled with symbolic meaning.

Murayghat thus contradicts traditional explanations for Early Bronze Age society. Rather than focusing on domestic settlements, the site reveals that ritual centers were independent, serving as communal spaces where alliances were reaffirmed, the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ were remembered, and a sense of belonging was rebuilt after the disintegration of society.

The study, published in Levant, is an example of how early societies adapted to crisis through ritual and the building of monuments.

More information: University of CopenhagenPublication: Kerner, S. (2025). Dolmens, standing stones and ritual in Murayghat. Levant: The Journal of the Council for British Research in the Levant, 57(2), 128–143. doi:10.1080/00758914.2025.2513829