Warning: Spoilers for One Battle After Another ahead

There’s an old adage that great movies teach you how to watch them, and I’ve found that to be true. Films have ways of drawing our eyes and ears to certain things, even without us noticing, that end up being the keys to understanding them, whether in terms of story or theme.

If you’re someone that likes to unpack movies for deeper meaning, or to peek under the hood to figure out how they made you feel the way they did, it pays to look out for how we’re being primed to pay attention.

In One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson does it with names. The French 75; Perfidia Beverly Hills; Steven J. Lockjaw; Junglepussy. They can’t help but stand out. And, naturally, we might spend the first few minutes of this movie wondering what those names mean.

That is a question in itself worth asking, to a certain extent. Perfidia is a Spanish word for treachery. Lockjaw, aside from being appropriate for the most тιԍнтly wound man on Earth, is a medical condition that’s a telltale sign of tetanus – an alarming symptom of a greater infection. Bob is a fun way of underscoring how out-of-place Leonardo DiCaprio’s protagonist has become. In this high-stakes world of revolutionaries and secret societies, he’s ultimately just a guy.

But there’s also more to it than that. These names are just a gateway to One Battle After Another‘s clever deployment of language, which sits at the heart of what the movie’s really about. I believe it’s the glue that allows it to hold so many things together at once – from its politics to its character dynamics to its multi-genre story structure – without any of them feeling diluted or unbalanced.

One Battle After Another’s Dialogue Requires A Different Kind Of Listening

Names in One Battle After Another tend to serve a purpose. They communicate something, to both other characters and the audience, beyond their definitions. This function is built directly into the underground revolutionary nature of the French 75, whose members use aliases to not only disguise their idenтιтies, but send a message. Their names are chosen, and that choice says a lot about how they want to be perceived.

Their organization’s name, for instance, refers neither to their nationality nor (seemingly) to their size. But it sounds cool, doesn’t it? It conjures an image of revolution (you know, the French one) while also sharing its name with a cocktail, which itself is supposedly named after WWI artillery. It feels like a name sturdy enough to carry the legend these rebels hope to leave behind, and was surely chosen for that reason.

With this, PTA plants a seed, and it sprouts fast. Suddenly, this distinction between what words mean and what purpose they serve is everywhere.

Lockjaw is a kind of bridge here. His name isn’t chosen, but his rank is given, and he accordingly bases his idenтιтy on external validation. His sense of masculinity is formed by such signifiers. So, when he corners Perfidia in a bathroom stall and says he only wants his hat and gun – two symbols of his military-created manhood – we understand he’s not just being literal.

Perfidia lecturing Pat (not yet Bob) on gender roles is another early example. She is chafing under the restricting responsibility of motherhood, but rather than say that, she hides her feelings behind her revolutionary rhetoric. Pat, to his credit, sees right through her and calls her on it. Even before her betrayal, we have no doubt that Perfidia leaving Pat and their daughter has nothing to do with an ideological commitment to the cause.

Both of these scenes flash One Battle After Another‘s secret talent, which should be the envy of screenwriters everywhere. Over the movie’s prologue, we are trained to approach dialogue subtextually – to almost ignore what is said, in favor how it was said and why. Speech is an action to be interpreted; it’s show-don’t-tell storytelling, if telling was also a kind of showing.

Once we’re primed to pay close attention to language and how it’s deployed, it becomes the fulcrum for all the film’s key interests.

Comrade Josh, Bad Hombre & Making It Clean: What It Means To Speak In Code

One Battle After Another is rife with codespeak. As a form, it’s not meant to be understood literally, but to serve a function. For revolutionaries at constant risk of discovery, it’s a useful tool for idenтιтy verification, but through Bob’s interactions with his former cohorts, the practice frequently veers into absurdity.

Deandra calling Bob to warn him of Lockjaw’s attack is his first instance of forgetting an identifying keyphrase, and also the first time that the person asking refuses to let it slide. This is, as it turns out, merely PTA setting the table – but it’s notable that Deandra does this despite clearly knowing who she’s speaking with. This is our first indication that the French 75 (or whatever this revolutionary network is now called) has let its practices become ritualistic.

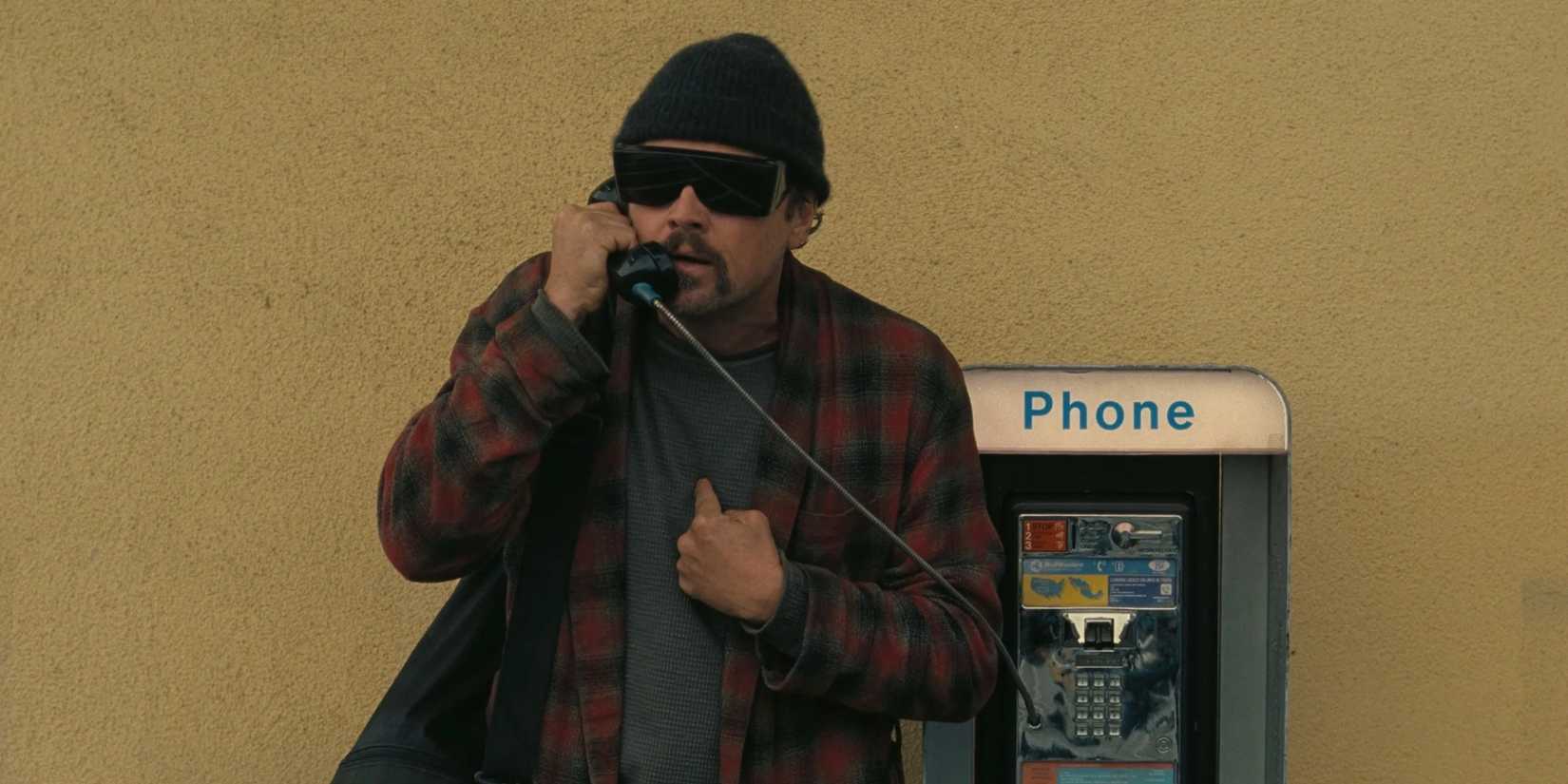

Then, Bob encounters Comrade Josh, the snide voice on the other end of the underground crisis H๏τline that becomes the bane of his existence. Though he gets through multiple layers of the code, effectively proving himself a member, Bob cannot remember the answer to “What time is it?“

Unlike Deandra, Josh doesn’t already know Bob, and the distressed dad’s pleas get him nowhere. Instead, Josh mocks him for not having studied the revolutionary texts with the proper dedication, and refuses to give him the rendezvous point.

Bob’s misbegotten phone calls are funny for the same reason that they’re a pointed, linguistic critique – the subtext of these coded exchanges isn’t what it’s supposed to be. If Deandra’s pᴀssword request was ritualistic, Josh’s is more like virtue signaling, and knowing the answer to the question has become more important than ascertaining who Bob really is.

As a result, a genuine life-threatening situation is tied up in the French 75’s now-bloated bureaucracy. Bob is only able to resolve it by exploiting that bureaucracy’s rules until he gets someone who actually knows him on the phone – and the final question he’s asked not only makes fun of the now-moot procedure, but actually does what the code is meant to do in the first place.

The goal of this is not merely to mock leftist fragmentation, but to strip political complications away from a much simpler truth: Coded language loses its effectiveness when divorced from its intended purpose.

In a critical point of contrast, Bob experiences the codespeak of Sensei Sergio’s younger, much more nimble resistance network. With a quick namedrop and the phrase “bad hombre,” which Sergio had used to describe him just once the day before, he’s clued into a scheme to smuggle him out of police custody before he’s identified by the authorities. It’s a thrilling scene that goes off without a hitch.

Sensei and his team use language to enact revolution; Comrade Josh and his fellow French 75ers use language to feel like revolutionaries.

As Sergio leads his people through that chaotic night in Baktan Cross, he doesn’t really ever speak in code – he speaks in Spanish. One Battle After Another leaves it unsubтιтled, simultaneously illustrating how it can function as code when up against enemies too arrogant to learn it and hammering home that these courageous rebels are just regular people, not a self-styled movement.

The Christmas Adventurers fill out the other end of that spectrum. Like the French 75, the name chosen by this secret society of white supremacists tells us how they want to be perceived, but they are notably not outward-facing; if it serves any external function, it’s to be benign enough not to arouse suspicion if discussed in public. The effect of their name is intended purely for their own membership.

Which makes it all the more sinister that, on top of the images of religion, family, and bright, white snow conjured by referencing Christmas, they cloak themselves in a whimsical grandeur. They want to see their beliefs as righteous and their mission as benevolent. They want their gatherings to feel warm, as if a refuge from the cold, cold world full of punk trash.

Unlike the revolutionaries, their use of coded speech is all ritual, no function. Hailing Saint Nick to start a meeting doesn’t serve a purpose when idenтιтies are already vetted; ordering someone to make it “clean” doesn’t actually disguise the request for multiple murders. It just saves them from the unpleasantness of having to say it aloud.

The Adventurers’ use of language is equal parts ridiculous and sinister. It’s an insightful fictionalization of the way that real right-wing hate groups engage in sanitization and lionization, often in ways that are unexpectedly bizarre. (Did you know the Proud Boys’ name traces back to a song written for but cut from Disney’s Aladdin? Well, now you do.)

Who Are You?: When Subtext Becomes Text

One Battle After Another‘s uses of naming and codespeak share a common theme: idenтιтy. If the prologue lays out how idenтιтies are constructed and presented, and the middle section plays with how idenтιтies are verified (even via paternity test), the climax is interested in who we really are underneath all that.

It’s through Willa’s journey that PTA gets us to that breaking point. Her arc has essentially been one of idenтιтy deconstruction – there’s hardly a scene she’s in that doesn’t challenge her previous sense of who she was.

She’s not just a normal high schooler with a paranoid burnout for a dad. Her mother isn’t ᴅᴇᴀᴅ, and she wasn’t a hero. Bob isn’t actually her father, and her real father is everything she’s been raised to stand against. Willa isn’t even the name she was born with.

By the film’s end, she’s facing certain death and scrambling to keep herself alive. But even if she survives, the person she used to be is already long gone.

Everything comes to a head in One Battle After Another‘s celebrated car chase. After outmaneuvering Tim Smith, the Christmas Adventurer sent to erase her, she uses French 75 code the way it was intended. Smith fails the check and gets sH๏τ ᴅᴇᴀᴅ. Soon after, Bob arrives, and Willa requests the code while holding him at gunpoint.

Once again, Bob is forced to remember a pᴀssword by someone who already knows who he is. But this time it’s different. After he gives the right answer, Willa prompts him again, this time speaking aloud the question that was always hiding underneath the code: “Who are you?“

It’s a loaded question for her. Since being separated from the man in front of her, she’s learned that he’s been lying to her for virtually her entire life; she may even wonder whether Bob was always aware of her true parentage.

Like many characters in One Battle After Another, Bob has many names, none of which are truly suitable answers. Instead, he simply insists to Willa that he’s her dad. In terms of formal verification, it’s actually been disproven, and based on the role-reversing exchange he and Willa had before Lockjaw disrupted their life in hiding, it’s not an idenтιтy that he’s done that great a job of constructing. But it’s who he really is.

From there, the movie wraps up by continuing to expose who its characters really are. Lockjaw’s authoritative, manicured exterior is ruined by a sH๏τgun to the face. The Christmas Adventurers’ final solution to their Lockjaw problem is about as unignorably Nazi-coded as it gets. And Willa, fueled by a revealing letter from the mother she never knew, embraces her revolutionary lineage with open arms.

In other words, we are what we do, regardless of what we say. It seems strange that a movie as complex and wonderful as One Battle After Another can boil down to so simple an idea – then again, the film demonstrates how complicated forming one’s idenтιтy can be in practice.

To circle back to names, that’s one way to interpret the movie’s тιтle. Who we are isn’t immutable, nor can it truly be shaped by the ways we present ourselves. It’s something we prove, over and over again, with each decision we make.

![Good Boy Ending Explained: Why [SPOILER] Doesn’t Die In The Finale Good Boy Ending Explained: Why [SPOILER] Doesn’t Die In The Finale](https://dx.laptrinhhocsinh.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/good-boy-poster-art.jpg)