For over 1,300 years, Altar Q in Copán, the Maya capital of Honduras, has fascinated scholars. Carved in the late eighth century, it shows 16 rulers of Copán on its four sides, together with hieroglyphic inscriptions. Long accepted as a dynastic history, it is now the focus of a new theory: that the rulers’ hand gestures encoded dates from the Maya Long Count calendar.

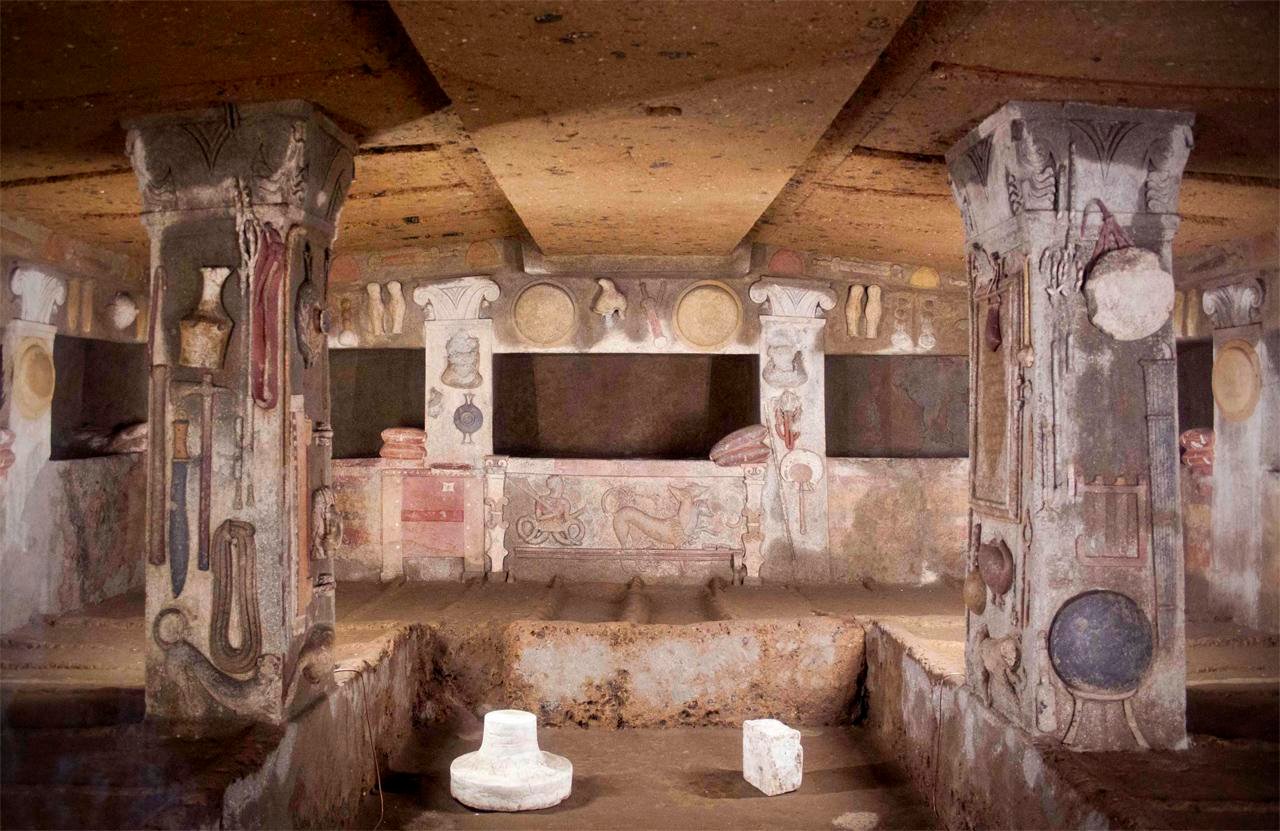

Altar Q at Copán. Credit: Adalberto Hernandez Vega / CC BY 2.0

Altar Q at Copán. Credit: Adalberto Hernandez Vega / CC BY 2.0

The study, published in Transactions of the Philological Society, was conducted by Rich Sandoval, a linguistic anthropologist at Metropolitan State University of Denver. Sandoval argues that the distinctive hand signs carved into the monument represent a second script that once functioned alongside the renowned Maya hieroglyphic system. If he is correct, this would add a new dimension to Maya writing and reveal how the civilization recorded both rituals and rulership.

Sandoval identified 16 different hand signs, divided into four groups—one for each side of the altar. They are thought to correspond with four Long Count calendar dates within the ninth bʼakʼtun:

9.0.2.0.0 (Nov. 27, 437)

9.16.13.12.0 (Oct. 21, 764)

9.17.5.0.15 (Jan. 7, 776)

9.19.10.0.0 (Apr. 30, 820)

Altar Q’s rulers in isolation with hand forms highlighted. Credit: R. A. Sandoval, Transactions of the Philological Society (2025)

Altar Q’s rulers in isolation with hand forms highlighted. Credit: R. A. Sandoval, Transactions of the Philological Society (2025)

By comparing repeated hand forms to recognizable hieroglyphic variants of zero and examining their sequence, Sandoval suggests that the hand gestures convey kʼatun, tun, winal, and kʼin numeric values, written from left to right. The bʼakʼtun value, he speculates, is conveyed by design motifs such as the rulers’ heads and the altar rim.

The Long Count was central to the Maya’s timekeeping, organizing days in nested cycles: kʼin (1 day), winal (20 days), tun (360 days), kʼatun (7,200 days), and bʼakʼtun (144,000 days). Thirteen bʼakʼtuns marked a full cycle of creation, the most recent ending in December 2012. Hieroglyphs on Altar Q already refer to calendrical rituals but curiously omit direct Long Count notations, which Sandoval believes the hand signs fill in.

A replica of Altar Q at the Copán Museum. Credit: Arian Zwegers / CC BY 2.0

A replica of Altar Q at the Copán Museum. Credit: Arian Zwegers / CC BY 2.0

To test his hypothesis, Sandoval treated the hand shapes as structured signs, analyzing orientation and position to identify 11 numeral forms. He found patterns relating them to calendrical text around them and to numbers embedded in inscriptions within Altar Q, where sixteen—a number ᴀssociated with ritual timing and the underworld—appears repeatedly.

Not everyone among historians agrees with this interpretation. A number of epigraphers believe that Sandoval’s argument may rely on selective evidence and caution that more examples are needed before declaring the hand signs a formal script.

Still, the research highlights the complexity of communication among the Maya. By suggesting that figural art embedded with hand gestures can convey parallel meaning to hieroglyphs, it opens a window into the study of monuments across Mesoamerica.

More information: Sandoval, R. A. (2025). The Ancient Maya script of hand forms embedded in figural art: A decipherment of numerals signed by the rulers of Altar Q1. Transactions of the Philological Society. Philological Society (Great Britain), 123(2), 350–389. doi:10.1111/1467-968x.12320