Deep inside the Rising Star cave system in South Africa, researchers have discovered what is possibly the oldest known evidence of deliberate burial by a non-human species of early hominin. The researchers, publishing in eLife, are studying Homo naledi, a small-brained species that lived more than 240,000 years ago, and they speculate that these distant human relatives may have practiced cultural mortuary activity before modern humans or Neanderthals.

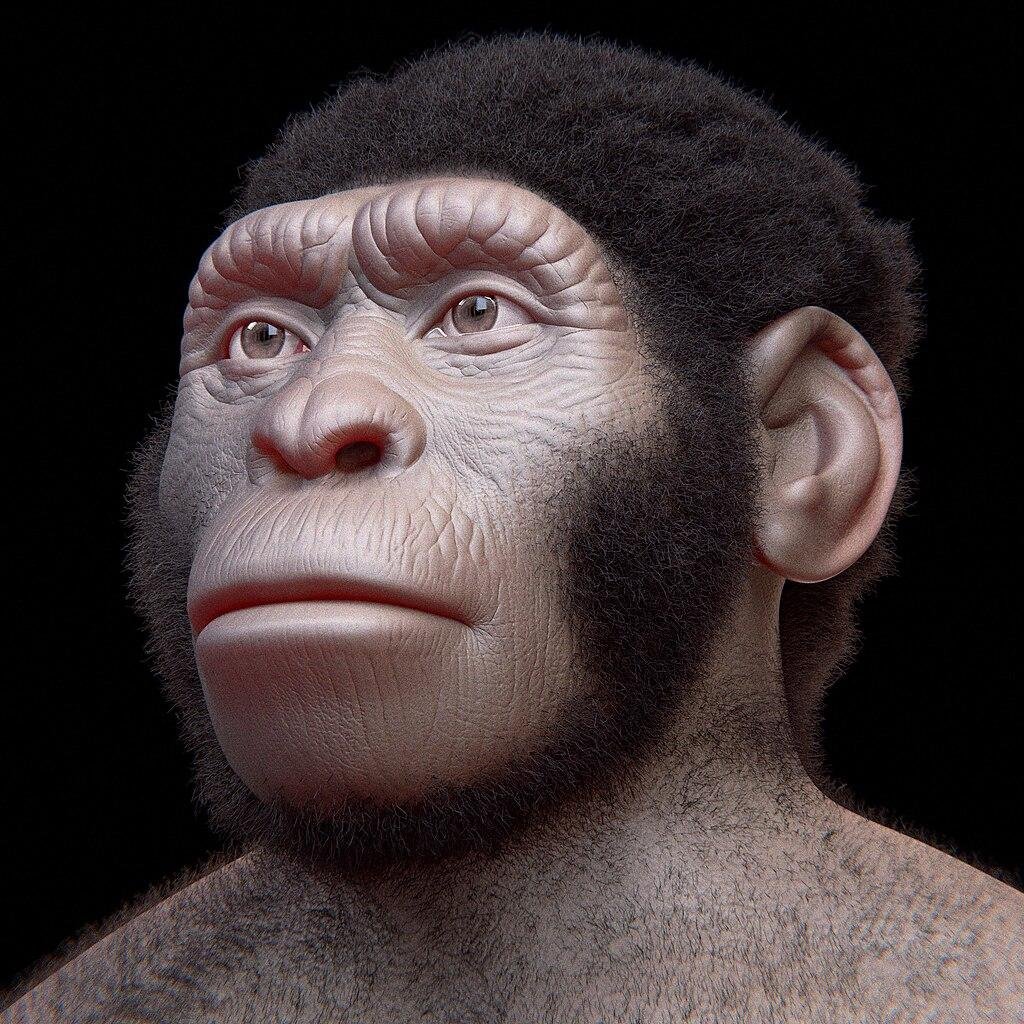

The Homo naledi facial reconstruction, performed with the coherent anatomical deformation technique. Credit: Cicero Moraes, CC BY 4.0

The Homo naledi facial reconstruction, performed with the coherent anatomical deformation technique. Credit: Cicero Moraes, CC BY 4.0

The quest began in 2013, when a team led by anthropologist Lee Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand initiated a daring excavation. Because the cave features narrow pᴀssages—entered only by descent through twisting shafts up to 30 meters deep—Berger recruited slim and highly fit researchers to navigate the dark, dangerous system. Their efforts produced one of the century’s most remarkable fossil discoveries: over 1,500 bones from at least 15 individuals of a newly recognized species, Homo naledi. The most concentrated section of the deposit, later named the “Puzzle Box,” contained unusually preserved fossils that appeared deliberately placed.

The latest round of excavations built on those discoveries with fresh work in 2017 and 2018 in the Hill Antechamber and the Dinaledi Chamber. There, scientists found additional concentrations of teeth and articulated bones, including juveniles and adults. Some skeletons even retained full anatomical connections, such as a foot and ankle still attached to a leg. Analysis of the sediment showed no evidence of water transport or slumping that might have carried bones into these chambers naturally. Instead, the fossils had apparently been placed there deliberately and then rapidly covered by sediment before the bodies had finished decomposing.

This is more a pattern of cultural burial than of natural processes. The authors of the study argue that the bones could not have been deposited by carnivores or by random geological events. Instead, the evidence indicates that Homo naledi brought their ᴅᴇᴀᴅ deliberately into the cave system and buried them. Most importantly, the caves show no evidence of occupation, further supporting the argument that they were used primarily as mortuary space.

Dinaledi Subsystem map and detail showing floor space of the Dinaledi Chamber and Hill Antechamber. Credit: L. R. Berger et al., eLife (2025)

Dinaledi Subsystem map and detail showing floor space of the Dinaledi Chamber and Hill Antechamber. Credit: L. R. Berger et al., eLife (2025)

The implications are immense. Deliberate burial was formerly considered unique to modern humans, tied to symbolic thinking, ritual, and even spiritual belief. Neanderthal burials, much debated in archaeology, had already shaken this image. Now Homo naledi, a little more than four feet high, with a brain just one-third the size of our own, could extend the date of mortuary practice back more than 100,000 years.

The Rising Star discoveries also expand our understanding of early human ancestors in new forms. Despite their small stature and primitive shoulder and hip formation, naledi had hands and feet very similar to modern humans. Carrying bodies far into deep, narrow caves would have required cooperation, planning, and possibly fire to navigate in total darkness. Whether motivated by practical considerations, such as keeping ᴅᴇᴀᴅ bodies out of sight of scavengers, or by symbolic and emotional motives, the action suggests cognitive sophistication unexpected for a species so far removed from modern humans.

Dinaledi Feature 1; (A) PH๏τogrammetric model of excavated units, including Dinaledi Feature 1 and part of Feature 2, from before the south-edge profile was cut. (B) Schematic of the excavated area, adjacent zones, and skeletal remains, showing all bones including those in unexcavated portions; exact boundaries and depth of remaining material are unknown. (C) Positions of excavated elements viewed from the east face; remaining in-feature elements are not shown. Credit: L. R. Berger et al., eLife (2025)

Dinaledi Feature 1; (A) PH๏τogrammetric model of excavated units, including Dinaledi Feature 1 and part of Feature 2, from before the south-edge profile was cut. (B) Schematic of the excavated area, adjacent zones, and skeletal remains, showing all bones including those in unexcavated portions; exact boundaries and depth of remaining material are unknown. (C) Positions of excavated elements viewed from the east face; remaining in-feature elements are not shown. Credit: L. R. Berger et al., eLife (2025)

However, there remain arguments. Archaeologists continue to struggle with the definition of evidence of cultural burial. Many prior claims, especially regarding Neanderthals, have been questioned after closer study. However, the evidence in Rising Star is characterized by the number of individuals involved, lack of disturbance by water or animals, and clear spatial separation of remains from surrounding sediments.

For now, the caves are the only known remains of Homo naledi, their daily lives and culture a mystery. But their burials—if confirmed—make us reconsider the very traits once presumed to make us human. The discovery suggests that symbolic or ritual behavior is deeper and more complex in the human lineage than ever previously thought.

More information: Berger, L. R., Makhubela, T. V., Molopyane, K., Krüger, A., Randolph-Quinney, P., Elliott, M., … Hawks, J. (2025). Evidence for deliberate burial of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ by Homo naledi. eLife, 12(RP89106). doi:10.7554/elife.89106.3