Hey y’all – it’s Liam Crowley, ScreenRant’s film reporter and host of Coffee Chats. I’ve been covering film professionally for five years but have been obsessed with this storytelling medium for triple that time. Who I am as a person is the sum of my favorite narratives and characters, and there is no genre I see myself in more than coming of age films. Coming of age films have been a staple of cinema for as long as the storytelling medium has been around. While the genre thrived in the 1980s and 1990s with тιтles like The Breakfast Club and Clueless, none compare to the entry that hit theaters in September 2012: The Perks of Being a Wallflower. Think I’m wrong? Let’s settle it in the comments.

The phrase “coming of age” within the English language has a fairly black and white definition. It means to reach adulthood. After decades of stories that explore this path out of adolescence, Hollywood has arguably taken ownership of the phrase, and by proxy, transformed it into something far more nuanced than its dictionary explanation.

And with that comes an ever-evolving translation of what it means to reach adulthood: navigating social hierarchies and playing the all-too-confusing dating game en route to discovering a sense of self as childhood innocence fades. Early entries like Little Women and Oliver Twist established themselves as timeless classics, but they are ultimately restricted when it comes to 1:1 audience immersion due to being reflective of a bygone era.

The greatest coming of age film needs to be a story that resonates with the very crowds who are actively experiencing the middle ground between adolescence and adulthood while simultaneously still reaching multiple generations of yesteryear, and there is no picture that encapsulates that better than The Perks of Being a Wallflower.

The Perks Of Being A Wallflower Is The Perfect Coming Of Age Story

From its story structure alone, The Perks of Being a Wallflower has all the necessities for, at the very least, a successful coming of age movie.

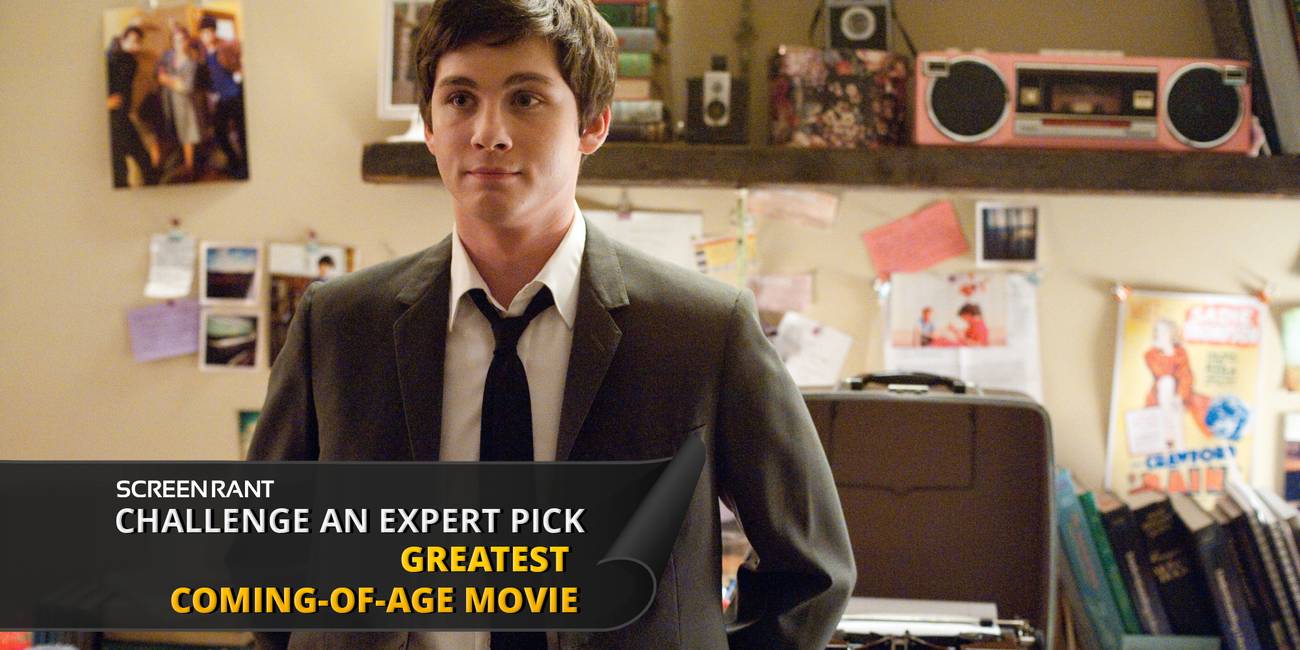

An awkward and shy yet rootable protagonist? Meet Charlie Kelmeckis (Logan Lerman). An overly intimidating setting packed with a contentious social hierarchy? Welcome to Mill Grove High School. An unattainable but oh-so-desired love interest that, in the pursuit, guides our protagonist towards self-discovery? More on that later.

What elevates The Perks of Being a Wallflower from enjoyable to elite is what’s built upon those foundational necessities. Charlie goes through the ringer as he tiptoes out of childhood, showcasing a deliberate dicH๏τomy of the highs and lows that come with his adult experiences.

His first time getting high leads to him being the life of the party, but a bad LSD trip later sends him to the hospital. His yearn for romantic connection eventually lands him a girlfriend, but it’s ultimately a one-sided relationship that he feels trapped in.

As he navigates this adolescent odyssey, Charlie’s new circumstances ultimately help guide him towards figuring out his life’s purpose. If not for Patrick (Ezra Miller) buying him a suit or Mr. Anderson (Paul Rudd) giving him book ᴀssignments, Charlie wouldn’t have embraced becoming a writer.

Like the dicH๏τomy of drugs and romance, that sense of self-discovery comes with an equal and opposite reaction, which is confronting childhood trauma, an encounter that comes with a cost.

The Perks Of Being A Wallflower’s Loss Of Innocence Exploration

The journey from adolescence to adulthood is far from a black and white exchange, but there is one key transactional piece that comes with it: loss of innocence.

A personal anecdote: when I was 8 years old, my mom raved about a new trainer at her gym, praising her for being energetic and efficient. Then one day, she told me that this trainer was suddenly fired for stealing gym equipment. I thought that to be impossible. My mom, a model citizen of humanity, declared that this trainer was nice, and nice people don’t steal!

That’s a very tame example of what it means to lose innocence. Charlie’s loss of innocence comes with the aforementioned drugs and romantic experimentations, but the deep, dark, repressed loss of innocence ultimately comes in acknowledging the truth of his past, as he is actively battling clinical depression while also being prone to PTSD-triggered anxiety attacks from the memories of his late aunt Sєxually ᴀssaulting him when he was a child.

Once audiences know the full grasp of who Charlie Kelmeckis is, you’re left yearning for the kid to simply find happiness. He doesn’t need to save the world. He doesn’t need to win the lottery. He just needs to find his smile. And in the grand scheme of life, that’s something we can all relate to. We are all fighting internal battles every day, dozens of which we tell no one but ourselves.

Logan Lerman’s Masterclass Performance

Many things have to go right for a film to work, but few are more important than a leading man’s performance. Logan Lerman is so lost in Charlie that you forget you’re even watching a movie. He nails every nuance.

The struggle to make eye contact when participating in class. The sporadic nervous breathing while confessing his feelings. The painfully awkward kiss to Sam when he dared to kiss the prettiest girl in the room. The ability to shed what are labeled as unwanted tears as he experiences a PTSD episode.

All of these subtleties are communicated behind historic coming of age lines of dialogue. Charlie’s timid question to Mr. Anderson, “Why do nice people choose the wrong people to date?” yields what is largely regarded as one of film’s most iconic lines: “We accept the love we think we deserve.”

My personal highlight of Lerman’s performance as Charlie comes in how he bowties the whole story. During the final tunnel drive with Sam and Patrick, Charlie remarks that “right now, these moments are not stories. This is happening.” That line is two-fold, as it applies to Charlie’s fictional journey but is also reflective to the adolescent audiences that are actively navigating their own coming of age stories in real time.

Chbosky’s story remains a formative film for audiences both young and old 13 years after hitting theaters, making it, as Charlie would say, “infinite.” The Perks of Being a Wallflower is the greatest coming of age story of all time, and I will defend it with my last breath.