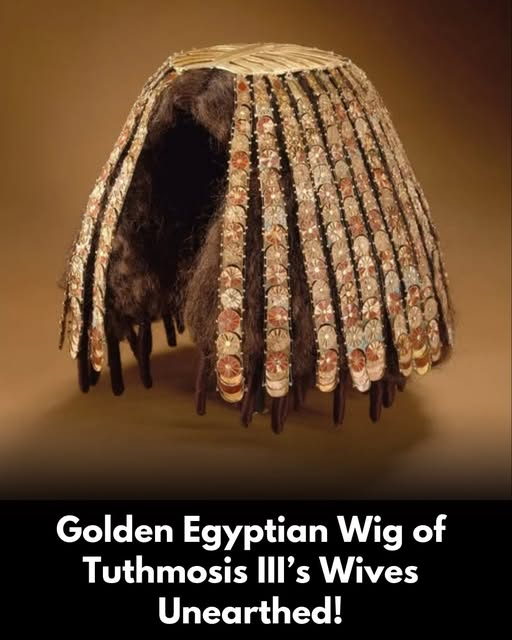

In the dry sands of Egypt, where the winds carry whispers of forgotten dynasties, a team of archaeologists brushed away grains of dust to reveal an artifact that seemed more a vision than reality—a golden wig once worn by the wives of Pharaoh Tuthmosis III. The object shimmered faintly under the desert sun, each strand of its ornate design reflecting not only gold but the weight of three thousand years of silence. What had been hidden beneath layers of sand was more than a relic—it was a window into a world of power, love, and intrigue.

The Pharaoh and His World

Tuthmosis III, often called the “Napoleon of Egypt,” ruled during the 18th Dynasty, a time when the Egyptian empire expanded beyond its borders, stretching deep into the Levant and south into Nubia. He was a warrior king, a visionary, and a ruler whose reign brought unprecedented wealth to the Nile Valley. But behind the grandeur of his military triumphs stood the women of his court, adorned with the finest jewels, silks, and gold that Egypt could offer.

The golden wig belonged to one of them—or perhaps it was a shared ceremonial adornment for many. Unlike wigs of simple reeds or human hair worn by commoners, this creation was reserved for the elite. Each strip of inlaid decoration glowed with lapis lazuli, carnelian, and turquoise—stones traded from the far corners of the empire, tokens of Egypt’s reach and dominance.

The First Glimpse

The excavation team found it in a tomb chamber near Thebes, a burial place that had remained untouched since the shifting sands had sealed its entrance. As the archaeologists’ torches lit the chamber, their eyes caught the halo-like reflection of gold resting among the decayed remains of cloth. For a moment, silence filled the chamber, each member of the team aware they were the first humans in over thirty centuries to witness this splendor.

One of the archaeologists later wrote in her journal: “It was not just an artifact. It felt like a presence, as though the woman who once wore it still lingered, proud and regal, unwilling to fade entirely into history.”

The Wig as a Symbol

To the ancient Egyptians, wigs were more than adornments. They were symbols of idenтιтy, power, and divine ᴀssociation. Pharaohs, priests, and nobility wore them not only for beauty but to embody a kind of sacred image. The golden wig unearthed here was not meant for daily use but for ceremonies—festivals where wives of the Pharaoh would stand beside him, shimmering embodiments of Hathor, goddess of beauty, love, and fertility.

Every strand carried symbolism. The gold represented eternity, incorruptible and divine. The embedded stones reflected cosmic order: lapis for the heavens, turquoise for rebirth, carnelian for the power of blood and life. To wear such an item was to transcend the human form and step briefly into the role of a living deity.

Whispers of the Women

But who wore this wig? Was it Satiah, Tuthmosis’s chief queen, who stood by him during his rise to power? Was it Merytre-Hatshepsut, the powerful royal wife who bore his successors? Or was it a collective heirloom, pᴀssed between the women of the court during rituals?

History has often silenced these women, their names mentioned only in pᴀssing compared to the grand exploits of their husband. Yet here, in this golden wig, their presence is undeniable. It tells us they were more than background figures; they were embodiments of prestige, carefully adorned to mirror the wealth and stability of the empire.

The Archaeologists’ Dilemma

Uncovering such an artifact brings both wonder and responsibility. As the team carefully cataloged each detail, they debated how best to preserve it. Some argued it should remain in Egypt, as part of the living memory of its people. Others believed it should travel the world, a symbol of Egypt’s legacy for all humanity to witness.

There was also the haunting question: should it be displayed at all? For some, disturbing such a sacred object was akin to trespᴀssing upon the resting spirits of the past. Could the wives of Tuthmosis III have imagined their intimate adornments would one day lie behind glᴀss, gazed upon by millions of strangers?

A Glimpse into Ancient Court Life

The wig also provides rare insight into the intimate world of the Egyptian court. Imagine the scene: the great palace in Thebes, columns painted in vivid blues and reds, incense smoke curling through the air. The wives of the Pharaoh prepare for a festival, attendants fitting this golden wig upon the head of the queen. Musicians strike their harps, priests chant hymns to Amun-Ra, and the golden strands of the wig catch the torchlight as the queen steps forward, dazzling the crowd.

For a brief moment, she is not just the wife of Tuthmosis III—she is Egypt itself, radiant, eternal, divine.

The Emotional Impact

For the modern observer, standing before the wig is overwhelming. It is not simply an object of beauty but a reminder of human longing—for power, for immortality, for remembrance. One feels both admiration for the artistry and sorrow for the silence of the lives once lived behind it.

Archaeology often reduces lives into artifacts, but here the artifact resurrects lives. The golden wig speaks without words, whispering of love, rivalry, pride, and the desire to be remembered beyond death.

The Legacy of Discovery

As the artifact was transported to Cairo for study, news spread quickly. Scholars and enthusiasts debated its significance, while Egyptians themselves reflected on the glory of their ancestors. Some felt pride that such a treasure had been preserved beneath their land, others felt unease—was this truly a discovery, or simply a reminder that the past never truly lets go?

The wig has since inspired exhibitions, books, and films, but perhaps its true legacy lies not in fame but in what it awakens within us: the awareness that human beings, across thousands of years, have always sought the same things—beauty, recognition, and permanence.

Closing Reflections

Standing before the wig today, one cannot help but wonder: what did the wives of Tuthmosis III think as they wore it? Did they feel empowered, elevated, or burdened by the weight of gold and expectation? Did they look at themselves in polished bronze mirrors and see a queen—or a prisoner of ritual?

The golden wig reminds us that history is not only about battles and kings, but about the quieter, personal moments—how a woman felt as she adorned herself, how she dreamed of being remembered.

And in that, perhaps, lies the true magic of archaeology: to not only uncover objects but to resurrect the humanity within them.