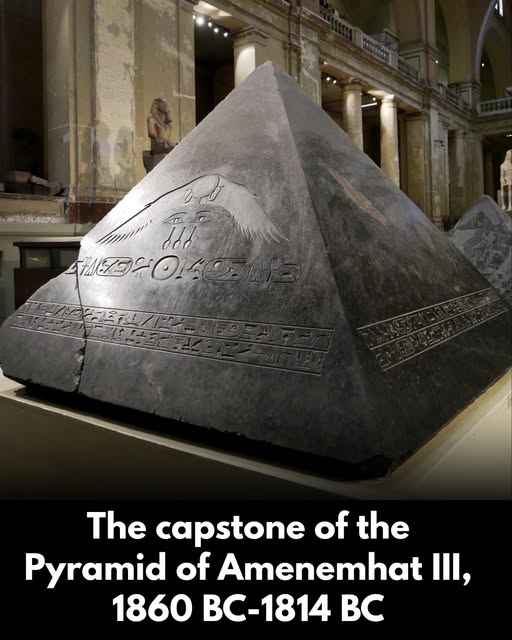

In the heart of Cairo’s Egyptian Museum, beneath the muted light of chandeliers that reflect faintly off ancient stone, rests a relic that once crowned a giant. It is not a mummy, nor a golden mask, but a pyramidion—a capstone, carved from black granite, inscribed with hieroglyphs, and once kissed by the desert sun nearly four thousand years ago. This single block of stone, modest in size compared to the colossi of Egypt, belonged to the Pyramid of Amenemhat III, a ruler whose reign was one of both brilliance and fragility.

To the untrained eye, it may seem like just another block—angular, worn by centuries, with faded carvings. But for the archaeologist, the historian, and even the poet, it is a voice. A whisper from an age when Egypt wrestled with its own mortality.

The Pharaoh Who Dreamed of Eternity

Amenemhat III, the sixth ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty, reigned during Egypt’s Middle Kingdom, a time often overshadowed by the grandeur of the Old Kingdom pyramids and the later glory of the New Kingdom pharaohs. Yet his reign, stretching from 1860 BC to 1814 BC, was marked by ambition.

He was a king who sought to tame both nature and time. The Nile, ever unpredictable, was harnessed through his ambitious irrigation projects. The Fayum Oasis, a vast depression west of the river, became fertile under his rule. He built colossal structures: two pyramids—one at Dahshur, known as the “Black Pyramid,” and another at Hawara, famed for the labyrinth that awed even Greek historians a thousand years later.

But even the might of Amenemhat III could not escape the creeping decay of stone. His Black Pyramid at Dahshur, once meant to be his eternal house, began to collapse even before his death. The ground beneath it betrayed him; cracks and fissures grew, and the structure weakened. Undeterred, he built again at Hawara, determined that his ka, his soul, would not wander without a home.

The capstone now resting in the museum once stood proudly at the apex of his pyramid—a shining point that touched the heavens. Ancient Egyptians believed the pyramidion was sacred, the stone that channeled the sun’s rays to the pharaoh’s resting place. Covered in gleaming white limestone in its day, the pyramid, with its dark granite tip, must have caught the first light of dawn and the last light of dusk, a beacon for both gods and men.

The Archaeologist’s Encounter

When modern archaeologists uncovered this capstone, they did more than find a block of granite. They rediscovered a chapter of human yearning. One archaeologist, upon brushing the dust from the carved wings of Horus spread across its face, reportedly paused longer than usual. He whispered, almost to himself, “So this is what he touched last.”

The stone carried not only inscriptions but fingerprints of ambition. Each chiseling mark, each carved hieroglyph of offering to Ra, spoke of artisans who toiled with both devotion and fear. They were not just building for their king; they were building for eternity.

And yet, eternity betrayed them.

The Human Thread

It is easy to lose ourselves in the grandeur of kings and monuments, but every block, every capstone, has a human thread. Imagine the stonemason—perhaps a man named Nebra—summoned from a village by the Nile. He had calloused hands and a son waiting at home. For months, perhaps years, he chipped away at the granite under the searing sun, his sweat soaking into the stone. Did he ever think that thousands of years later, strangers from lands he could never imagine would gaze at his work behind glᴀss?

For Nebra, the capstone was not just stone—it was a promise. A promise that the king would live forever, and in that eternity, so too would the names of those who built for him. To fail was unthinkable. To finish was a glory.

Time’s Betrayal

But time has little mercy for kings. The pyramid at Hawara, though sturdier than Dahshur’s Black Pyramid, eventually eroded. Robbers stripped it. Floodwaters damaged its chambers. The great labyrinth that once stood beside it, described by Herodotus as rivaling the pyramids themselves, crumbled into ruin.

And yet—this capstone survived.

Why? Perhaps because it was too heavy, too plain in the eyes of tomb robbers seeking gold. Perhaps because it was half-buried, shielded by sand. Or perhaps, as the priests might have whispered, because it was guarded by the falcon wings of Horus carved into its face.

Today, it is all that remains intact from the apex of Amenemhat’s vision. The pharaoh’s body may be lost, his pyramid a ruin, but his final stone rests unbroken.

A Modern Reflection

Standing before the capstone, modern visitors often feel something strange. Some describe awe, others sadness. A teacher from France once wrote in the museum’s guest book: “It feels like the top of the world has fallen to the ground.”

That sentiment captures the paradox of Egypt’s monuments: they were meant to defy time, yet they crumble. And in their ruins, they remind us of our own fragility.

Perhaps that is the true gift of Amenemhat’s capstone—not as a relic of power, but as a mirror. It asks us: What do we build that lasts? Will our cities, our machines, our digital empires endure four thousand years? Or will all that remains be a single fragment, a survivor of ambition, misunderstood but still alive?

The Silent Witness

The capstone does not speak in words, but in silence. It has witnessed the rise and fall of kingdoms, the march of armies, the sweep of empires. It saw the Persians conquer Egypt, the Greeks carve their temples, the Romans raise their banners. It was there, buried, when Napoleon’s scholars arrived with wide eyes and notebooks, when Victorian adventurers dug in the sand, when planes first flew over the Nile.

It is more than stone. It is memory.

Epilogue: The Eternal Question

As I stand before it now, I cannot help but imagine Amenemhat himself, watching. Did he succeed? Did he find eternity in the afterlife, or does his spirit hover around this capstone, waiting for someone to understand?

Perhaps eternity was never meant to be a literal preservation of body and stone. Perhaps eternity is the act of being remembered, even imperfectly, thousands of years later. If so, Amenemhat III lives on—in the granite gleam of his pyramidion, in the whispers of archaeologists, in the eyes of visitors who pause just a moment longer than expected.

And maybe that is enough.