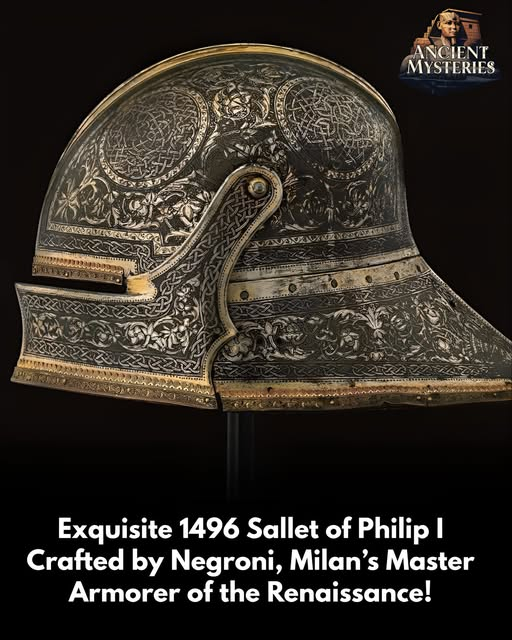

In the quiet halls of a museum, where centuries of history rest behind glᴀss and shadows, there stands a helmet that gleams not just with polished steel, but with the brilliance of human artistry, ambition, and survival. This is no ordinary piece of armor. It is the sallet of Philip I, crafted in 1496 by Negroni, Milan’s famed master armorer. More than a war-helmet, it is a jewel of the Renaissance — a crown of steel that carries the whispers of knights, the scent of battlefields, and the glory of princely courts.

To understand this piece is to step into a world where art and war intertwined, where craftsmen forged armor as beautiful as it was ᴅᴇᴀᴅly, and where rulers saw in such creations not only protection, but also power, status, and immortality.

Milan: The Beating Heart of Renaissance Armor

By the late 15th century, Milan had become Europe’s greatest forge of arms and armor. The Italian city was not just a hub of commerce and politics but also a cradle of invention. While Florence boasted of its artists and Venice of its merchants, Milan’s pride lay in its steel — a craft pᴀssed from father to son, perfected by generations of smiths who turned cold iron into something alive with strength and beauty.

Negroni, the armorer behind Philip’s sallet, was among the city’s finest. Known as a master of intricate etching and gilded steel, he was part craftsman, part artist, and part magician. His works did not merely shield a warrior’s head; they announced rank, wealth, and divine favor. When a nobleman donned Negroni’s armor, he wore both a weapon and a masterpiece — a canvas of steel etched with prayers, patterns, and symbols of authority.

The Sallet: More Than a Helmet

The sallet was the helmet of choice in Renaissance Europe, evolving from the simple war helms of the Middle Ages into something more refined. Shaped to fit the head snugly, with a visor to guard the face and a curve to deflect enemy blows, it represented the perfect balance of form and function.

But Philip’s sallet went beyond practicality. Its surface is a gallery of Renaissance artistry: vines twisting into knots of eternity, flowers blooming in eternal steel, and delicate scrollwork etched with precision. Gilded highlights shimmer along the edges, catching the light as though the helmet itself had been kissed by fire. This was no soldier’s helm — it was a prince’s crown, forged not of gold but of tempered steel.

Imagine Philip I riding into a tournament, sunlight flashing across his helm. To the crowd, he would not simply appear as a man in armor, but as a living statue, a knight made divine by the radiance of craftsmanship. His enemies, too, would see more than a fighter; they would see a man shielded by artistry, protected by symbols that suggested both earthly wealth and heavenly blessing.

War, Pageantry, and Idenтιтy

Armor like this sallet was seldom used in brutal battlefield combat, where mud, blood, and sweat wore down even the finest steel. Instead, it often belonged to the world of courts and pageants — jousts, tournaments, and ceremonies where nobles displayed not just their martial skill but also their prestige.

In such events, armor became theater. Each helmet, breastplate, and gauntlet told a story: of lineage, of alliances, of power. The patterns etched into Philip’s sallet may have carried hidden meanings — perhaps emblems of his family, prayers for victory, or symbols meant to intimidate rivals.

The Renaissance was a time when image mattered as much as swordsmanship. A prince did not simply fight; he performed. And his armor was his stage costume, crafted by masters like Negroni who understood that steel could be as expressive as marble, paint, or poetry.

The Man Behind the Helmet

Philip I, whose name is tied to this sallet, was part of a world caught between medieval traditions and Renaissance modernity. He lived in an era when knights still charged with lances, but gunpowder already roared across Europe’s battlefields. The sallet, for all its artistry, belonged to the twilight of armored chivalry.

What might Philip have felt when he first placed this helm upon his head? Pride, no doubt, in the craftsmanship. Comfort, perhaps, in the sense of security it gave. But also the weight of legacy — for armor was not only about survival, it was about memory. To wear a piece so finely crafted was to step into the role of a living legend, a man expected to live up to the magnificence of his appearance.

The Survival of a Masterpiece

That this helmet has survived more than five centuries is itself a miracle. Countless suits of armor were melted down for their steel, stripped for parts, or simply abandoned as useless relics once gunpowder rendered them obsolete. Yet Philip’s sallet endured — protected perhaps because of its beauty, cherished as a work of art even when its function faded.

Today, resting in stillness under museum lights, it no longer guards a prince in battle. Instead, it guards memory — the memory of Renaissance splendor, of Milan’s master armorers, of a world where war and art walked hand in hand.

A Crown of Steel, A Story of Humanity

To stand before this sallet is to feel the paradox of history: that something built for war can now inspire peace, that an object of defense has become a symbol of artistry, and that steel — cold, unyielding — can carry the warmth of human imagination across centuries.

It tells us that history is not only written in books but etched into metal, carved into stone, woven into cloth. It tells us that even in times of violence, humanity seeks beauty. And it reminds us that behind every artifact lies a human hand, a beating heart, and a story waiting to be told.

Final Reflection

The sallet of Philip I is more than just armor. It is a Renaissance crown, not of gold but of steel, forged by Negroni’s genius and worn by a prince who lived in a world poised between tradition and change. It is a reminder that history is not merely a record of battles and kings, but also of craftsmen, artists, and dreamers who infused even instruments of war with grace and meaning.

And as we gaze upon it now, we are invited to ask ourselves: what will survive of our age? What objects, five hundred years from now, will stand as symbols of who we were — our struggles, our ambitions, our artistry?

The sallet, in its quiet gleam, does not answer. It simply endures, a steel witness to the truth that humanity has always sought to leave beauty behind, even in the shadow of war.