In the dimly lit halls of a museum in Iraq, there rests a fragment of the ancient world that whispers across five thousand years of silence. To most who pᴀss by, it is just a broken slab of clay, its surface etched with symbols few can read. Yet to those who listen closely, this tablet from Uruk, the cradle of civilization, tells a story not just of kings and temples, but of humanity’s eternal longing to understand the heavens.

The city of Uruk—birthplace of writing, law, and myth—was once a teeming center of power and mystery. Around 3000 BCE, its streets echoed with the steps of priests, scribes, and merchants, and above them towered the ziggurat of Anu, the sky god. But in the quiet chambers of scholars, another pursuit consumed their days and nights: the mapping of the sky. It was here that cuneiform signs first captured not only the trade of goods and decrees of rulers, but also the movement of stars and planets.

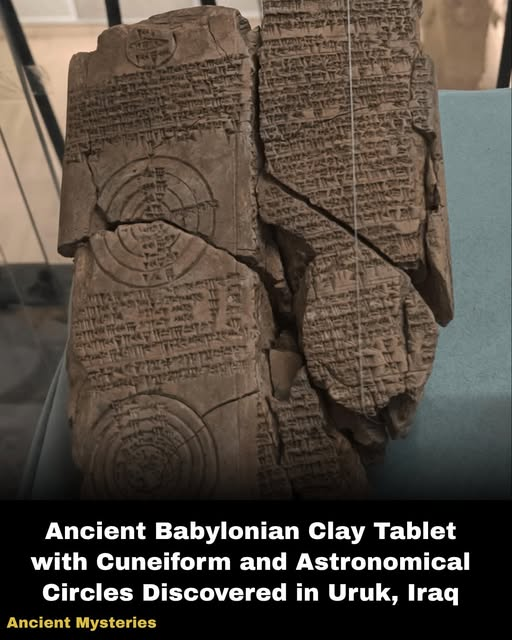

This clay tablet, though cracked and incomplete, carries a remarkable duality. Its surface is inscribed with the wedge-shaped cuneiform script of the Babylonians, chronicling celestial events. Around the text, carved circles radiate outward like ripples of water—astronomical diagrams drawn by hands that lived in a world without telescopes, yet who saw the cosmos with startling clarity. To touch this artifact is to bridge the distance between then and now, to feel the pulse of human curiosity that has never ceased.

Archaeologists who unearthed it in Uruk stood in awe. For here was not a myth, not a poem, but mathematics and observation baked into clay. The Babylonians recorded lunar eclipses, planetary alignments, and cycles of Venus with astonishing precision. Some scholars even argue that they anticipated principles of trigonometry long before the Greeks. What makes this particular tablet extraordinary are the concentric circles—perhaps maps of the heavens, perhaps symbolic diagrams of divine order. Were these sketches primitive charts of constellations, or something more esoteric, a reflection of a cosmic order they believed governed both gods and men?

Imagine, for a moment, the scribe who made this. By the flicker of oil lamps, he pressed a reed stylus into wet clay. Each stroke was a prayer, each mark a key to unlock the mysteries above. Perhaps he worked under the watchful gaze of a temple priest, tasked with recording omens from the skies. For in Babylonian thought, astronomy and astrology were inseparable. The stars were not distant fires; they were the writing of the gods themselves, and to read them was to know fate.

The circles carved into the clay may have guided the priesthood as they traced the paths of planets across the night sky. To the Babylonians, Jupiter was the star of Marduk, king of the gods; Venus was Ishtar, goddess of love and war. Their rising and setting foretold victories, plagues, and floods. Thus, this tablet was not merely scientific—it was sacred.

And yet, beneath its religious use, one cannot help but sense the raw human desire for knowledge. The same urge that led these ancient scholars to scratch circles into clay is the one that drives modern astronomers to launch telescopes into orbit. When we gaze at this tablet, cracked by time, we see ourselves reflected.

But history, like the stars, moves in cycles. When Uruk fell into ruin and its temples crumbled, tablets like this were buried beneath layers of earth, forgotten. Centuries pᴀssed. Empires rose and fell—the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans—while beneath their feet lay the records of a people who first dared to count the sky. When archaeologists finally uncovered these fragments in the 19th and 20th centuries, it was as though the voices of Babylon had spoken again.

What emotions stir when we realize that much of modern astronomy rests upon these silent beginnings? The Babylonians charted the Saros cycle, predicting eclipses with accuracy that astonished modern scholars. They invented a system of counting based on sixty—still alive in our sixty minutes and 360 degrees. This small tablet, scarred by time, is not just an artifact; it is a reminder that the roots of our science lie not only in Greece or Rome, but deep in the soil of Mesopotamia.

And yet, there remains mystery. Some researchers suggest that the tablet’s circles may depict not only astronomical cycles but also something symbolic, perhaps a cosmological vision of the universe itself. Were the Babylonians describing the heavens as a layered sphere, much like later Greek models of the cosmos? Or were they preserving an even older memory, a vision inherited from Sumerian myths of the gods descending from the stars?

For every answer it gives, the tablet raises new questions. Who first looked up at the night sky and thought to mark its order into clay? Did they sense, as we do, that we are not separate from the stars but made of the same dust? Was this artifact a tool of power, used by kings and priests to control the people with divine omens, or was it a sincere attempt to understand humanity’s place in the cosmos?

Archaeology is often thought of as the study of stones and bones, but in truth it is the study of ourselves. Each fragment we unearth reflects the eternal human struggle with time, death, and meaning. This Babylonian clay tablet is a mirror across millennia, showing that long before telescopes, long before science as we know it, human beings were already reaching outward, already daring to map the infinite.

Standing before it today, you might feel a hush within you. The museum lights gleam across its cracked surface, shadows filling the deep cuts of its cuneiform lines. Around you, the world rushes forward with technology and noise, yet here in this silent relic is the heartbeat of something eternal. The clay, once soft beneath a scribe’s hands, now hardened by centuries, carries the dreams of a civilization that believed knowledge was sacred.

We live in an age where stars are measured with satellites, where planets are pH๏τographed by probes at the edge of the solar system. And yet, the awe we feel when staring into the night sky is no different from that of a Babylonian gazing upward five thousand years ago. This tablet is proof: humanity has always been searching. Searching for meaning, for order, for our place among the stars.

Perhaps the most haunting thought of all is this: what if the knowledge we rediscover today is only a fragment of what was once known? What other tablets, still buried in sand and silence, wait to remind us of forgotten wisdom? The story of the stars is also the story of humanity—and each discovery pushes us further into that mystery.

So the Babylonian tablet remains, a broken yet powerful relic. Its circles are both maps and metaphors, its script both data and devotion. It reminds us that history is not a straight line but a great wheel, turning endlessly, carrying our questions forward. And though civilizations may fall, though time may bury even the greatest works, the human desire to reach beyond the horizon endures.

As you stand before it, you might ask yourself: what will we leave behind for the future to discover? What fragments of our knowledge, our hopes, our fears, will tell our story five thousand years from now?

The Babylonian clay tablet whispers across the ages: we have always sought the stars. And in that search, we find not only the heavens, but ourselves.