A set of ancient stone tools found on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi has pushed back the timeline for human habitation of the region by hundreds of thousands of years, confirming that early human relatives made a major oceanic crossing to arrive on the island much earlier than previously thought.

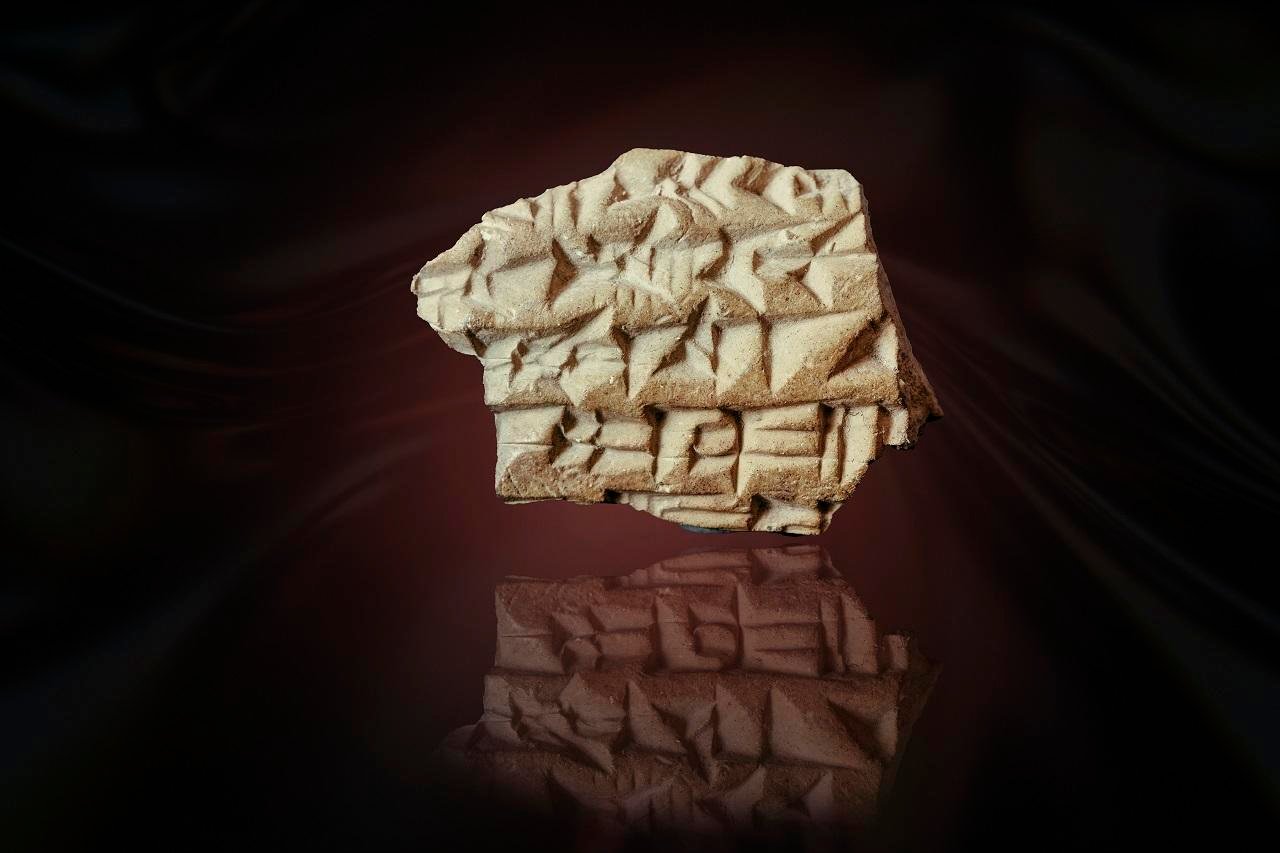

A reconstruction of Homo floresiensis. Credit: Paolo C / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

A reconstruction of Homo floresiensis. Credit: Paolo C / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The discovery, made by researchers from Griffith University in Australia and Indonesia’s National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), was published in the journal Nature. The scientists, led jointly by Griffith University’s Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution Professor Adam Brumm and Indonesian archaeologist Budianto Hakim, found seven stone artifacts at Calio, a southern Sulawesi site, during fieldwork between 2019 and 2022.

The artifacts—small, sharp stone flakes of chert—were produced by percussion flaking, a process in which larger pebbles are struck to produce sharp tools. One of the flakes even showed evidence of retouching to create a sharper cutting edge. The tools would have been used for food processing or crafting tools from wood or plant material, but no animal bones with cut marks have so far been found.

Dating techniques, including paleomagnetic analysis of the sandstone layers and uranium-series and electron spin resonance dating of a fossilized pig molar tooth, indicated that the tools were at least 1.04 million years old, and perhaps as much as 1.48 million years old. This makes them the oldest documented record of hominin presence in Wallacea—a chain of islands between the Australian and Asian continental shelves—and predating comparable discoveries on the Philippines’ Luzon Island (approximately 700,000 years ago) and Sulawesi’s own Talepu site (approximately 194,000 years ago).

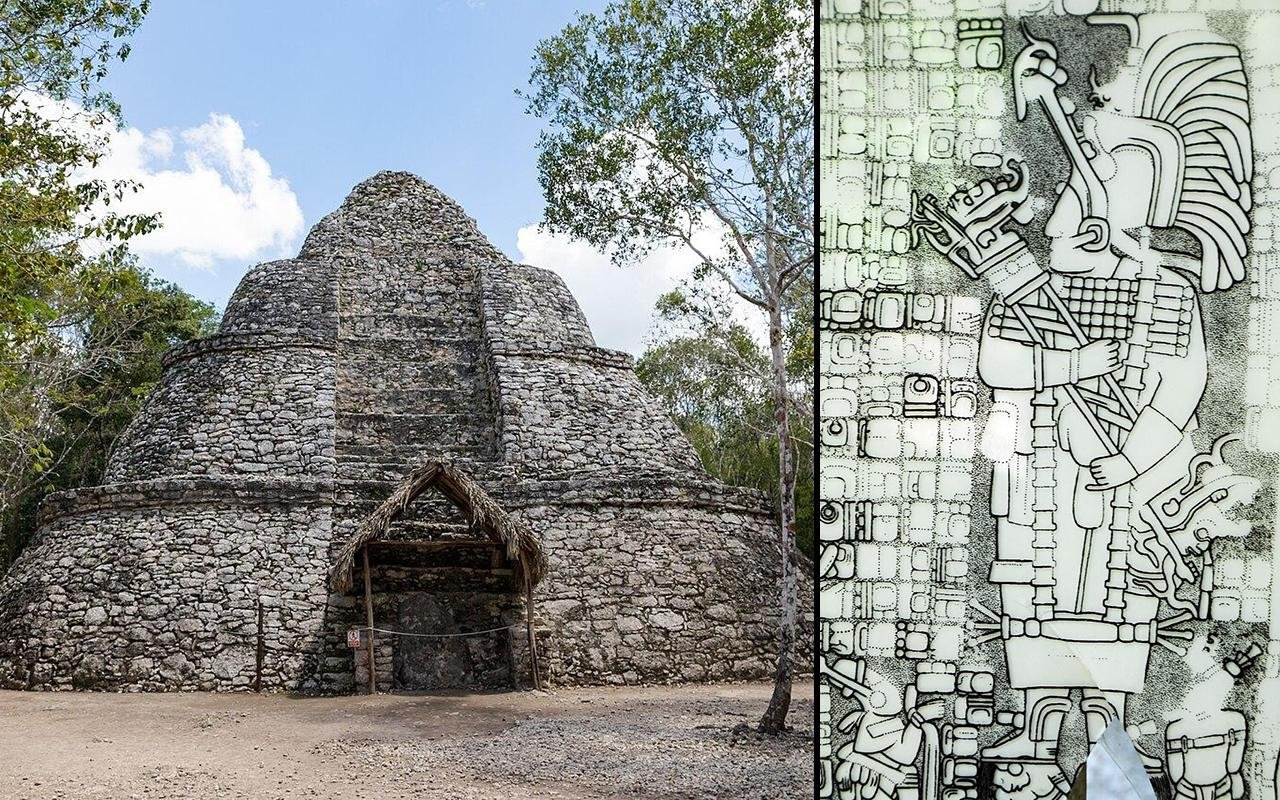

Stone tools dated to over 1.04mya, scale bars are 10mm. Credit: M W Moore / CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Stone tools dated to over 1.04mya, scale bars are 10mm. Credit: M W Moore / CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

“This discovery adds to our understanding of the movement of extinct humans across the Wallace Line, a transitional zone beyond which unique and often quite peculiar animal species evolved in isolation,” said Professor Brumm. “It’s a significant piece of the puzzle, but the Calio site has yet to yield any hominin fossils, so while we now know there were tool-makers on Sulawesi a million years ago, their idenтιтy remains a mystery.”

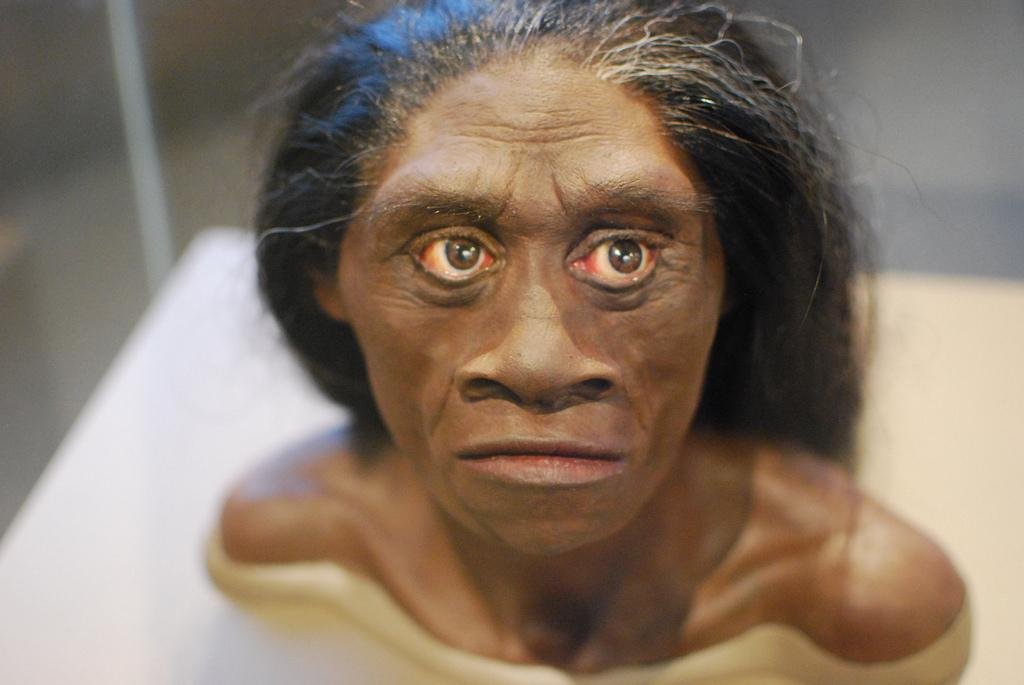

Given the age of the tools, researchers are convinced that they were either produced by Homo erectus, which is thought to have spread to nearby Java around 1.6 million years ago, or by one of their close relatives, such as the small-bodied Homo floresiensis. Brumm further said that his team believes the Flores hominins may have originated from Sulawesi before spreading south.

Reconstruction of the head of a Homo floresiensis individual, as on display at the Smithsonian’s Natural Museum of Natural History. Credit: Karen Neoh, via flickr / CC BY 2.0

Reconstruction of the head of a Homo floresiensis individual, as on display at the Smithsonian’s Natural Museum of Natural History. Credit: Karen Neoh, via flickr / CC BY 2.0

The find also raises questions about how these ancient humans adapted to Sulawesi’s vast and ecologically rich landscape. “Sulawesi is a wild card—it’s like a mini-continent in itself,” Brumm said. “If hominins were cut off on this huge island for a million years, would they have undergone the same evolutionary changes as the Flores hobbits? Or would something totally different have happened?”

Though Sulawesi is already famous for the world’s oldest known narrative cave art—more than 51,200 years old—the new discoveries suggest that the island has a history of early humans dating much earlier, when early hominins managed to perform impressive seafaring feats, crossing deep-ocean channels long before modern humans ever appeared.

More information: Griffith University

Publication: Hakim, B., Wibowo, U.P., van den Bergh, G.D. et al. (2025). Hominins on Sulawesi during the Early Pleistocene. Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09348-6