More than 6,000 years ago, in the Krumlov Forest of South Moravia in the Czech Republic, two sisters endured a hard life in an ancient mining settlement. Now, thanks to advanced forensic methods and archaeological research, their incredibly lifelike faces have been uncovered in new 3D reconstructions. These reconstructions give us not just a glimpse into their physical appearance but also into a society that may have exploited its most vulnerable members.

Anthropological reconstruction of the sisters. (pH๏τo by F. Fojtík). Credit: E. Vaníčková, et al., Archaeolo Anthropol Sci (2025)

Anthropological reconstruction of the sisters. (pH๏τo by F. Fojtík). Credit: E. Vaníčková, et al., Archaeolo Anthropol Sci (2025)

The remains were first discovered over 15 years ago during excavations at a Neolithic chert (flint) mine—specifically, Pit 4, one of hundreds discovered in the area, which is known for prehistoric mining activity from the Mesolithic to the Iron Age. The remains included two adult females buried one atop the other, with the older woman hugging a newborn baby on her chest. Next to them was a partially complete skeleton of a small dog. The females were likely sisters and were interred in the shaft in which they had labored, according to a paper published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

Dr. Martin Oliva, an archaeologist with the Moravian Museum and a co-author of the study, told Live Science that the location of the women’s graves within the mine suggests that the women likely labored there. The mine may have also had spiritual meaning, serving as a sacred site related to ancestral or sacrificial rituals, the researchers suggest.

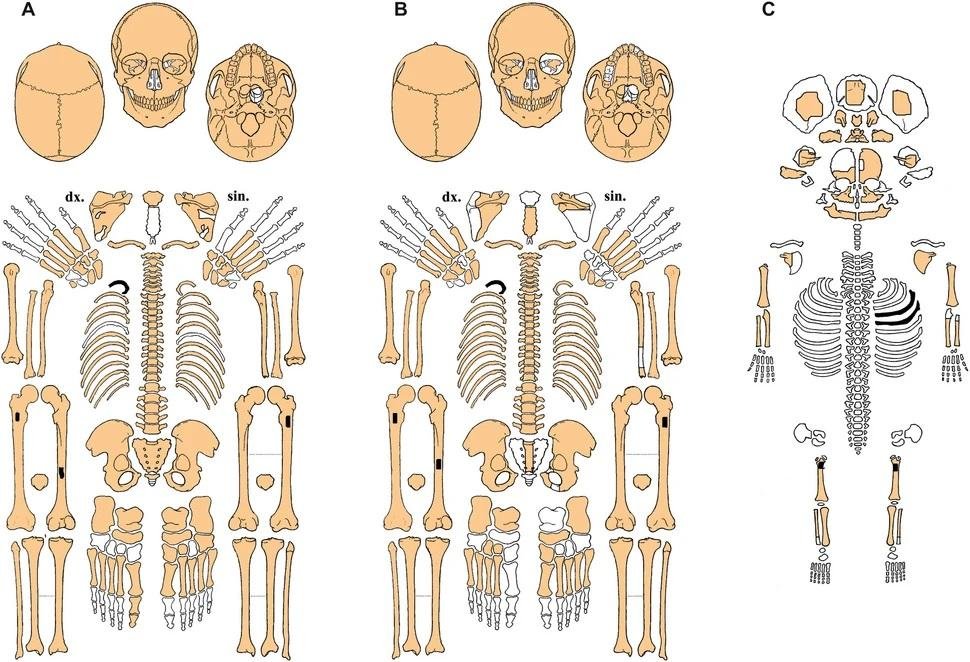

Detailed analysis, involving radiocarbon dating, genetic analysis, isotopic analysis, and bone study, paints a grim picture of physical suffering and exploitation. Both women, estimated to have been around 30 to 40 years old, were around 1.48 and 1.46 meters (approximately 4.8 feet) tall and bore signs of heavy labor. The bones exhibited worn vertebrae, early arthritis, herniated discs, and partially healed fractures—specifically, one on the older sister’s forearm—indicating that they continued to work despite severe trauma.

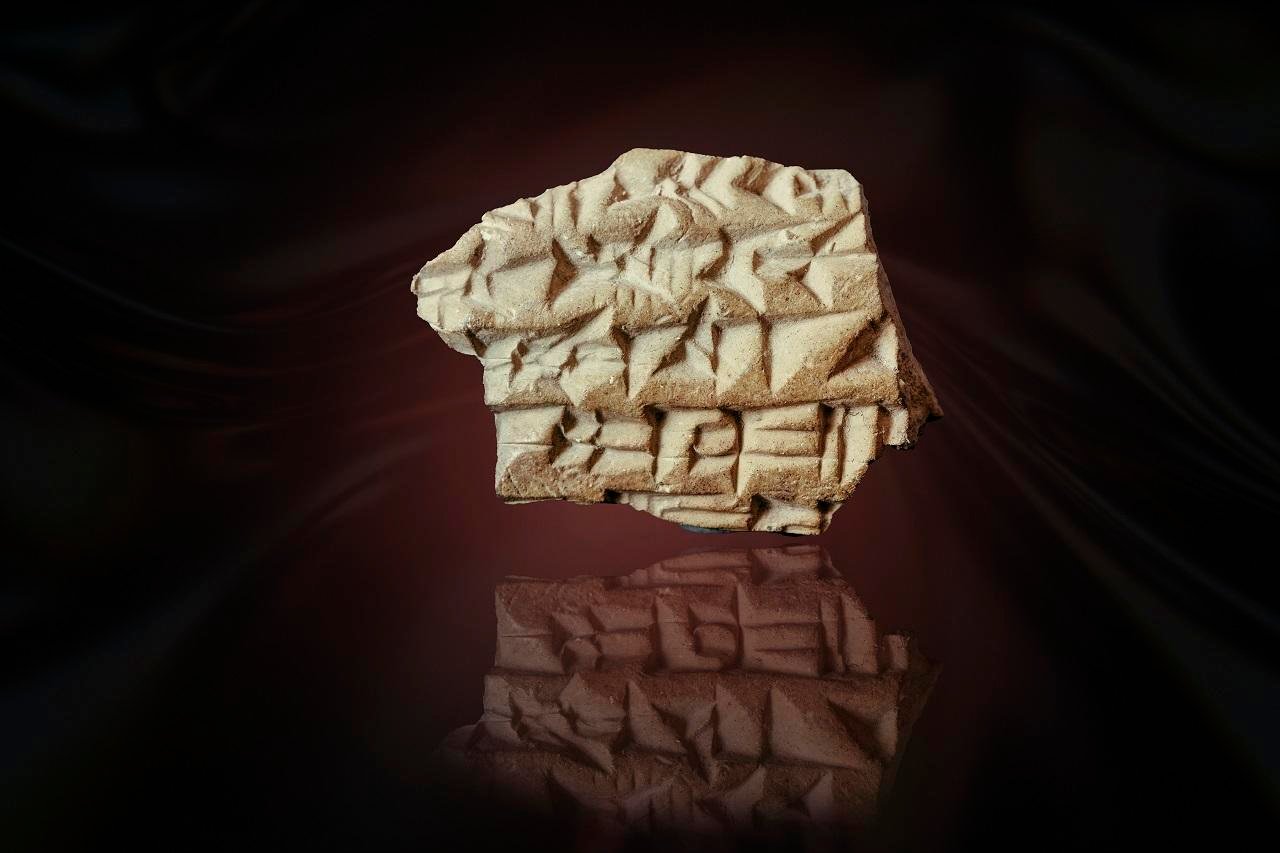

Preservation scheme, skeleton H1 (A), H2a (B), H2b (C) (drawing by I. Jarošová and M. Fojtová). Credit: E. Vaníčková, et al., Archaeolo Anthropol Sci (2025)

Preservation scheme, skeleton H1 (A), H2a (B), H2b (C) (drawing by I. Jarošová and M. Fojtová). Credit: E. Vaníčková, et al., Archaeolo Anthropol Sci (2025)

Interestingly, isotopic analysis of nitrogen and carbon levels indicated that although the sisters had grown up malnourished and ill, in adulthood, they had consumed a high-meat diet. This was unusual for European Neolithic populations, which may have been due to better access to wild game in the densely forested region or a nutritional strategy to fuel their hard labor.

DNA testing confirmed the sibling relationship and even determined some physical features. The younger sister likely had dark hair and green or hazel eyes, while the older may have had blue eyes and blonde hair. These features were utilized for the lifelike facial reconstructions—on display today at the Moravian Museum in Brno—created using plaster, silicone, prosthetic eyes, and implanted hair. The skulls were in a good state and allowed for detailed facial modeling.

Skull of female H2a enface (A) and skull of female H1 enface (B) (pH๏τo byF. Fojtík). Credit: E. Vaníčková, et al., Archaeolo Anthropol Sci (2025)

Skull of female H2a enface (A) and skull of female H1 enface (B) (pH๏τo byF. Fojtík). Credit: E. Vaníčková, et al., Archaeolo Anthropol Sci (2025)

The reconstructions also depict clothing derived from Neolithic-era archaeological textile finds, made entirely of plant fibers like flax and nettles. The older woman wears a simple blouse and plant-fiber wrap, and a hairnet. The younger one wears a linen blouse with braided fabric strips woven through her hair.

But questions remain. The infant that was buried was genetically not related to either woman, and the positioning of the dog’s remains adds another question mark to the burial. Scientists have not ruled out that the women and infant could have been victims of ritual sacrifice or symbolic appeasement to the earth, as mining shafts could have had spiritual significance to Neolithic peoples.

In the broader social context, the authors point to a possible reorganization of work in the Neolithic period. The article contends that as soon as hierarchical societies began to emerge, “the hardest labour may no longer have been done by the strongest, but by those who could most easily be forced to do it.” This is a hint that even in early agricultural societies, labor might have been distributed in unequal forms, possibly on the basis of gender, age, or social status.

More information: Vaníčková, E., Vymazalová, K., Vargová, L. et al. (2025). Ritual Burials in a Prehistoric Mining Shaft in the Krumlov Forest (Czechia). Archaeol Anthropol Sci 17, 146. doi:10.1007/s12520-025-02251-1