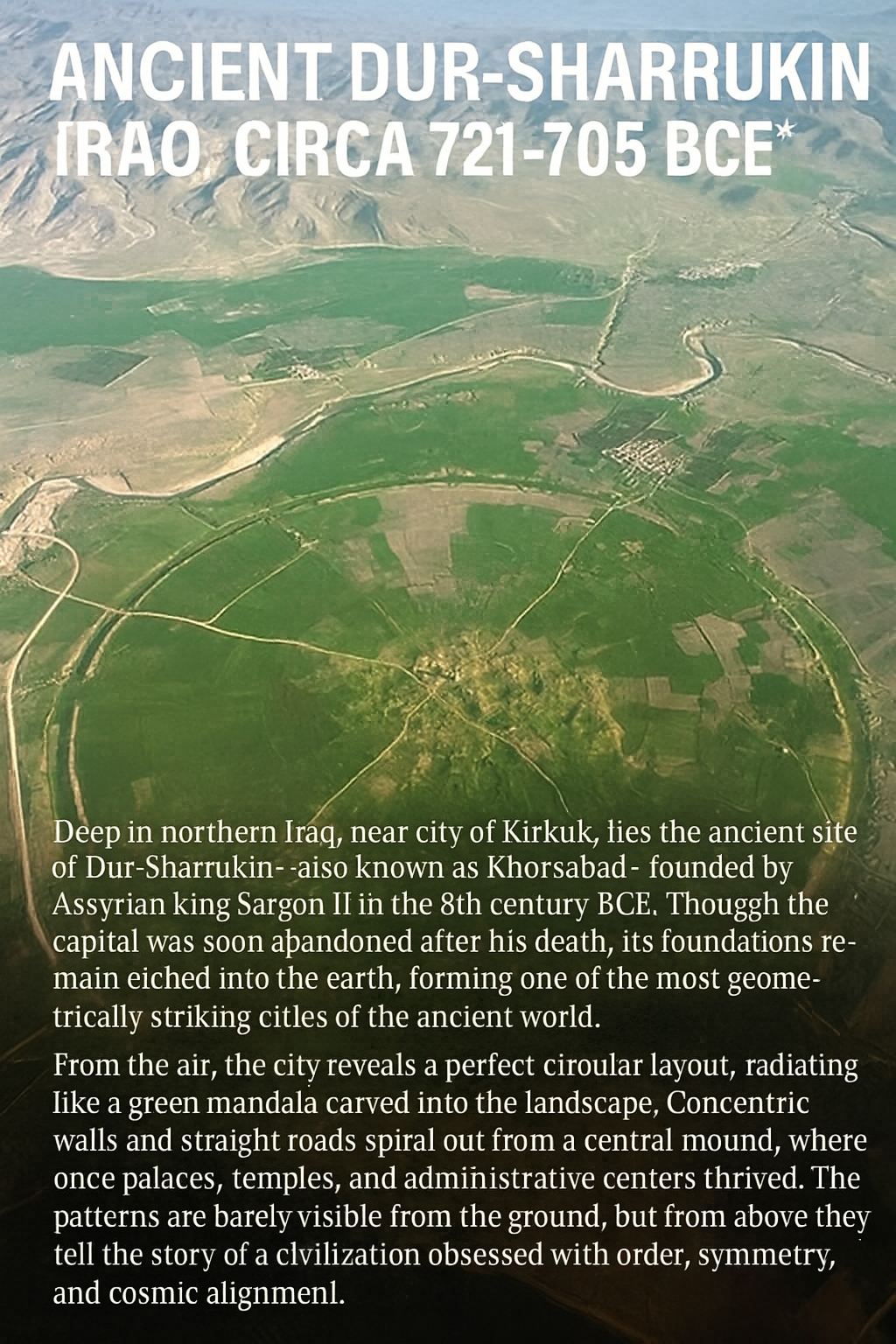

In the arid heart of northern Iraq, not far from modern-day Kirkuk, lie the remnants of Dur-Sharrukin—“Fortress of Sargon”—a city carved from ambition by the ᴀssyrian king Sargon II in the 8th century BCE. Though the city was abandoned shortly after the king’s death, its immense geometric imprint remains etched into the land, a fossil of imperial vision scorched into the soil by time itself.

From the sky, the city reveals itself in haunting clarity: a perfect circle laid like a green mandala across the plains. Concentric walls once rose from this design, with wide roads spiraling outward from a central mound—believed to be the site of palaces, temples, and command centers. Like the blueprint of a forgotten order, this urban geometry speaks of a people who worshipped symmetry as much as gods.

How strange, that the higher we rise above the earth, the more clearly ancient intent is seen. What once appeared as scattered stone becomes a celestial diagram—a glimpse into a civilization obsessed with precision, divine alignment, and the quiet permanence of shape. Was it a city, or a message meant for the heavens?