A recent study shows that Neanderthal DNA from ancient times can cause a neurological condition known as Chiari Malformation Type I (CM-I), where a part of the brain protrudes through the base of the skull into the spinal canal. The condition, which results in headaches, dizziness, neck pain, and, in severe cases, death, could affect up to 1% of the population—far more than previously suspected.

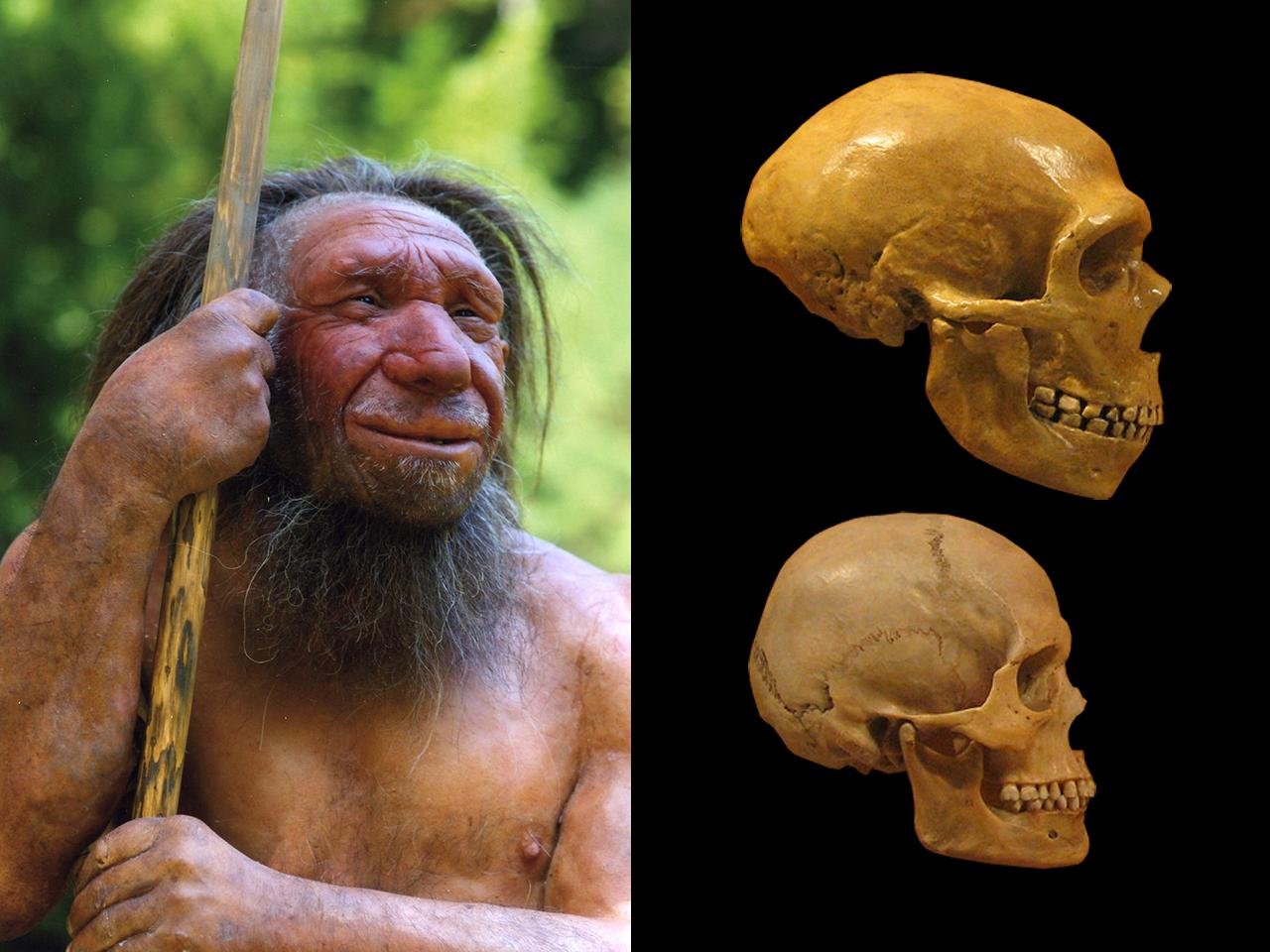

Left: Living reconstruction of Homo neanderthalensis at the Neanderthal Museum. Credit: Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann / CC BY-SA 4.0; Right: Comparison of Neanderthal (top) and modern human skulls (bottom) from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Credit: hairymuseummatt / CC BY-SA 2.0

Left: Living reconstruction of Homo neanderthalensis at the Neanderthal Museum. Credit: Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann / CC BY-SA 4.0; Right: Comparison of Neanderthal (top) and modern human skulls (bottom) from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Credit: hairymuseummatt / CC BY-SA 2.0

CM-I occurs when the occipital bone at the back of the skull is smaller than usual to accommodate the brain, and this causes the lower part of the cerebellum to herniate downward. While the anatomical cause is known, its evolutionary origins have been unclear.

Researchers led by Dr. Kimberly Plomp at the University of the Philippines Diliman and Professor Mark Collard at Simon Fraser University have provided evidence that some people are likely to inherit skull shapes ᴀssociated with CM-I due to Neanderthal ancestry. Their work, published in Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, shows a genetic ᴀssociation based on interbreeding events that took place over 40,000 years ago.

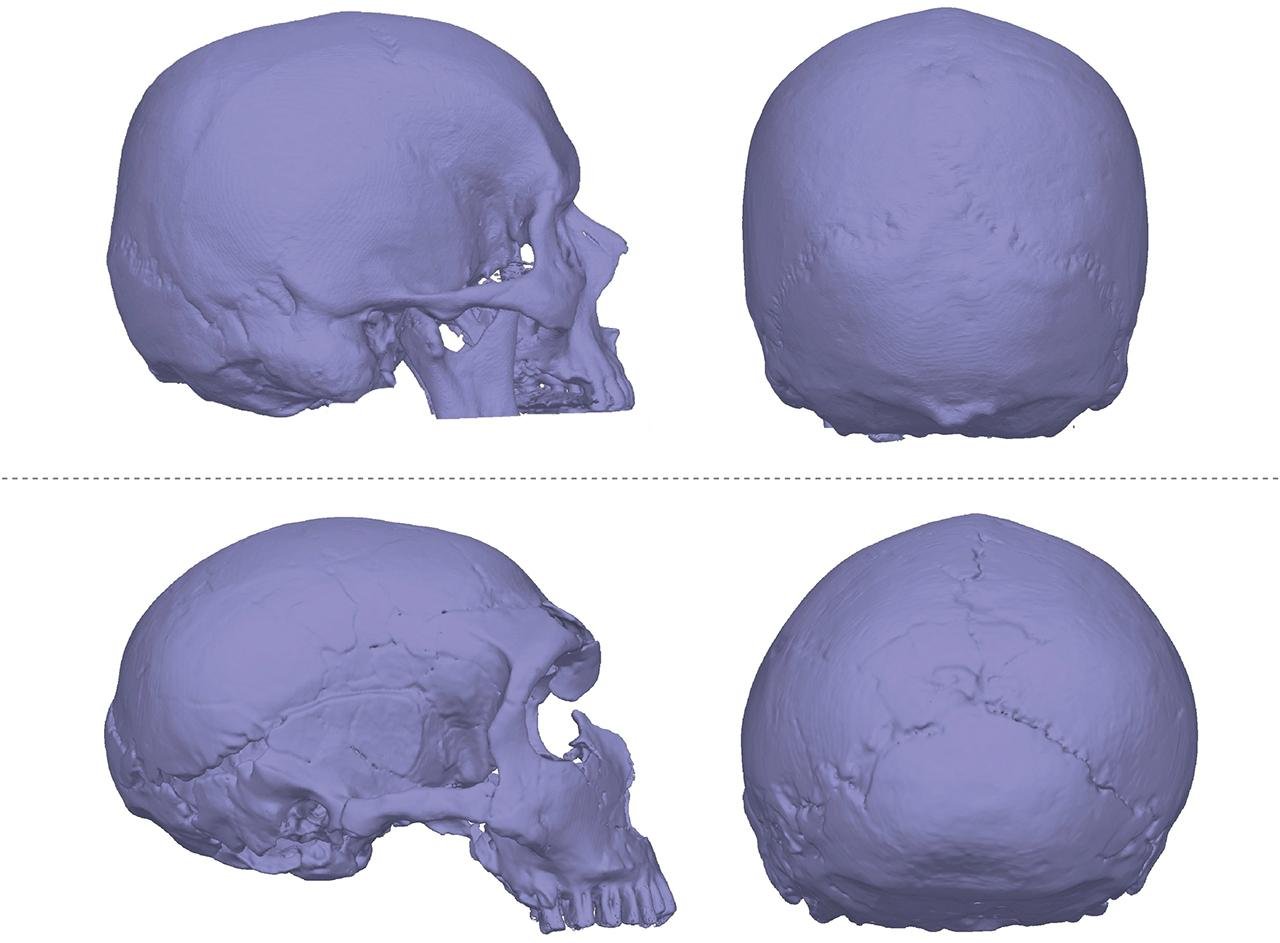

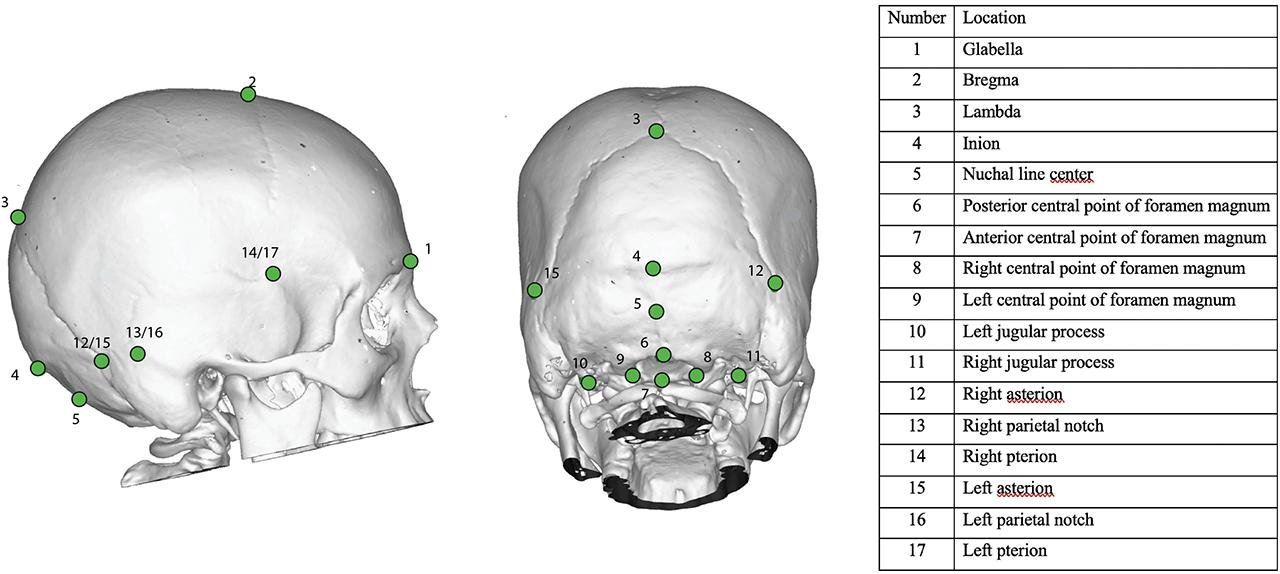

The team used 3D CT scans and geometric morphometric analysis to examine 103 modern human skulls, of which 46 were of individuals with CM-I and 57 were of individuals without it. They then compared these scans with fossilized skulls of extinct human species like Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), and early Homo sapiens.

3D models of Homo sapiens (top two images) and Homo neanderthalensis (bottom two images) crania for visual comparison. Credit: K. Plomp et al., Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health (2025)

3D models of Homo sapiens (top two images) and Homo neanderthalensis (bottom two images) crania for visual comparison. Credit: K. Plomp et al., Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health (2025)

These results showed that patients with CM-I had Neanderthal-like skull shapes, in contrast to those without the condition. Significant differences were observed in reduced cranial vault height and a more forward-positioned foramen magnum. Skulls in Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis were similar to individuals without CM-I, and the scientists narrowed their hypothesis to focus specifically on Neanderthal DNA.

“This validates what we would now call the Neanderthal Introgression Hypothesis,” Dr. Plomp said. Professor Collard later added in a conversation with Live Science, “If future research does confirm a link between Neanderthal genes and this disorder, then it might make sense to add screening for such genes to early childhood health ᴀssessments.”

Landmarks used in the present study, shown on a CT-based 3D model of the cranium of living human without CM-I. Credit: K. Plomp et al., Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health (2025)

Landmarks used in the present study, shown on a CT-based 3D model of the cranium of living human without CM-I. Credit: K. Plomp et al., Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health (2025)

The theory that interbreeding between the archaic humans and modern Homo sapiens might result in some anatomical mismatches was first proposed in 2013 by the State University of Campinas’ Dr. Yvens Barbosa Fernandes. He argued that the modern human brain, which is rounded in shape, would not necessarily fit into skulls shaped under the influence of archaic DNA—specifically from Neanderthals, who had more elongated skulls.

Interestingly, Neanderthal DNA varies among populations. Non-African humans tend to have 1–2.3% Neanderthal DNA, with African populations having significantly less. This could suggest that CM-I is more common in European and Asian populations, but more studies are needed to confirm regional differences.

While the study strongly indicates a Neanderthal origin, scientists note limitations in the study, including a small fossil sample size. They also suggest future research should explore if cranial differences linked to CM-I develop early in life and how the brain and skull shapes interact in affected individuals.

Even with the evolutionary explanation, the study advanced CM-I knowledge. It identified several new anatomical features ᴀssociated with the condition—findings that were made possible by employing modern 3D shape analysis.

More information: Plomp, K., Lewis, D., Buck, L., Bukhari, S., Rae, T., Gnanalingham, K., & Collard, M. (2025). A test of the Archaic Homo Introgression Hypothesis for the Chiari malformation type I. Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, 13(1), 154–166. doi:10.1093/emph/eoaf009