In the quiet hills of Lancashire, where the wind carries whispers from another age, there stands a fortress not just of stone, but of memory. Hoghton Tower, noble and enduring, rises from the earth like a watchman of the centuries, its walls soaked in centuries of hope, rebellion, loyalty, and blood. Walk through its gates, and you are no longer in the present. You have crossed into a world where history breathes beneath your feet.

The year was 1643. England was cleaved in two. Brother against brother, Parliament against Crown. The English Civil War had torn across the land like a storm of fire and steel, and Hoghton Tower, with its elevated vantage and impenetrable gatehouse, stood not just as a home—but as a stronghold. Its owners, proud Royalists, had thrown in their lot with King Charles I. And so the tower, with its thick curtain walls and battlements, became a garrison, a last bastion for the King’s men in a county fiercely contested.

But Hoghton Tower’s tale begins long before muskets and war cries echoed across its cobbled courtyard.

Built in the late 16th century by Thomas Hoghton, the manor was more than a house—it was a statement. A declaration of ambition. Rising over 560 feet above sea level, it commanded views across the Ribble Valley to the Irish Sea. Its placement was strategic. But its purpose was grandeur. Here, amidst the Lancashire moors, the Hoghton family declared their status not just to neighbors, but to the Crown itself.

In August 1617, King James I came to stay. The visit was legendary, and so, it is said, was the feast. At Hoghton, the king dined so lavishly that when presented with a loin of beef, he is believed to have drawn his sword and knighted it, declaring it “Sir Loin”—a tale that would ripple through English folklore for centuries.

But the glory would be fleeting. Within a generation, England would collapse into war. And Hoghton Tower, once a home of royal celebration, would become a fortress of royal defiance.

It was fortified quickly—too quickly. There were no vast arsenals or trained troops. Just loyal men, a few cannon, and the resolve of a family not ready to yield. But the Parliamentarian forces were strong, ruthless, and better equipped. In 1643, they came for the tower.

The siege was brutal. Gunpowder shook the hillside. Shattered stone and splintered wood rained down like confetti at a funeral. And then silence. When the smoke cleared, the tower lay broken—its upper works destroyed, its walls scorched, its defenders either slain or scattered. For nearly 150 years after, Hoghton Tower would remain a ruin, hollowed like a ribcage stripped of its heart.

But still, it endured. Because stones, unlike men, do not die easily.

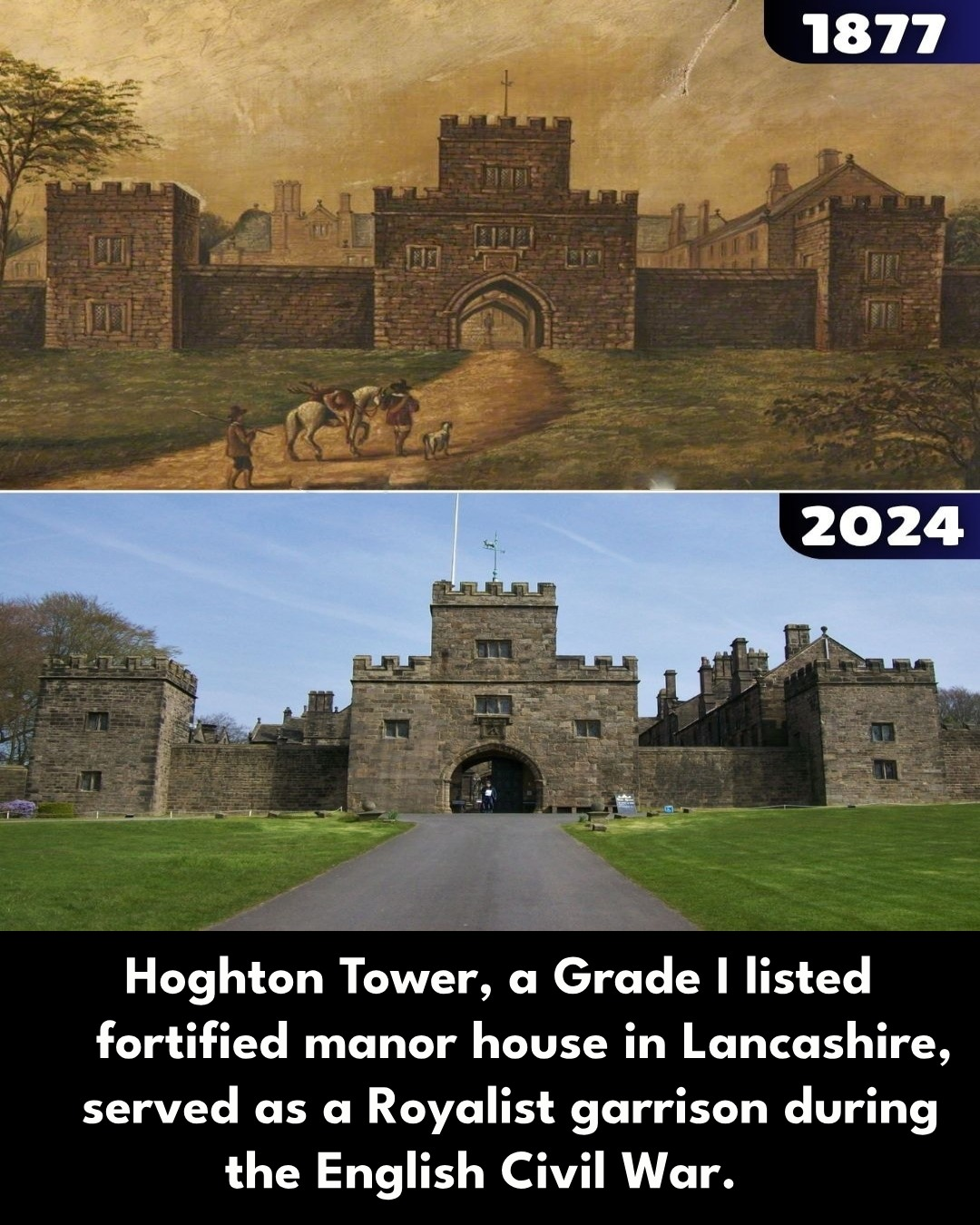

In the 19th century, the ruins stirred. Sir Henry de Hoghton, descendant of the proud Royalist line, began a slow, deliberate resurrection. The Victorian era, with all its romantic longing for the chivalry of ages past, breathed new life into the old tower. Gothic elements were restored, the courtyard repaved, the grand halls reimagined. By 1877, artists had captured its restored majesty in oils—its battlements once again bold, its archways like mouths holding secrets.

Then came modernity. Electricity. Motorcars. Wars that dwarfed the civil conflict of centuries before. Through it all, Hoghton Tower stood—never again a battleground, but always a witness.

Archaeologists have probed its grounds, brushing centuries of soil from pottery shards, cannon fragments, and musket balls. In the cellars, vaults once used to store wine or grain are now historical touchstones—echo chambers of ghostly whispers. Beneath the gatehouse, ancient pᴀssages twist through the stone like veins. Some say they were escape routes; others claim they were used to hide priests during the Reformation’s dark days. Whatever the truth, each corridor adds another thread to the tapestry of this place.

And yet, Hoghton Tower is no museum of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ. It is alive.

Today, its halls host weddings, its grounds echo with laughter, and its chambers welcome guests once more. Children run where soldiers once fell. Tourists dine where kings once feasted. It is history not behind glᴀss, but under your fingertips.

The de Hoghton family still resides within these walls—the same blood that stood for the Crown, that watched from the ramparts as Parliament’s troops stormed the gates. That lineage has not broken. It has bent, evolved, survived. As has the tower.

There is something about Hoghton Tower that defies time. Look at the old painting from 1877: the same stone, the same defiant gatehouse, a little weathered but proud. Now look at the pH๏τograph from 2024. It has not changed. Or perhaps we are the ones who have.

The path leading up is smoother now, flanked by manicured lawns instead of trodden earth. But the tower’s silhouette—those castellated turrets and central archway—remains untouched. Like a guardian standing against the ever-turning tide of history.

It is a paradox. A place once shattered by war now embodies peace. A site of bloodshed now echoes with music. A home that once armed itself against change now welcomes it.

And still, the stones remember.

They remember the thunder of hooves on dirt. The solemn tread of soldiers into the great hall. The trembling hands lighting torches in secret corridors. The cheers of a banquet and the sobs of surrender. They remember the crack of musket fire, the prayers before battle, and the silence after loss.

In a way, Hoghton Tower is not just a relic. It is a survivor. Like a scar turned beautiful with age. It teaches us that history is not a straight line, but a spiral—forever returning, revisiting, reminding.

And so when you stand before it today, whether in mist or sunshine, you do not just see a building. You see the English Civil War’s smoke curling into the sky. You hear King James’s laughter over roasted venison. You feel the ghosts of servants, of rebels, of lovers who met beneath the moonlit parapets.

More than anything, you realize this: Hoghton Tower is not only a monument to what was. It is proof that some things—dignity, legacy, memory—do not perish with time. They are built stone by stone, day by day, soul by soul.

And they endure.