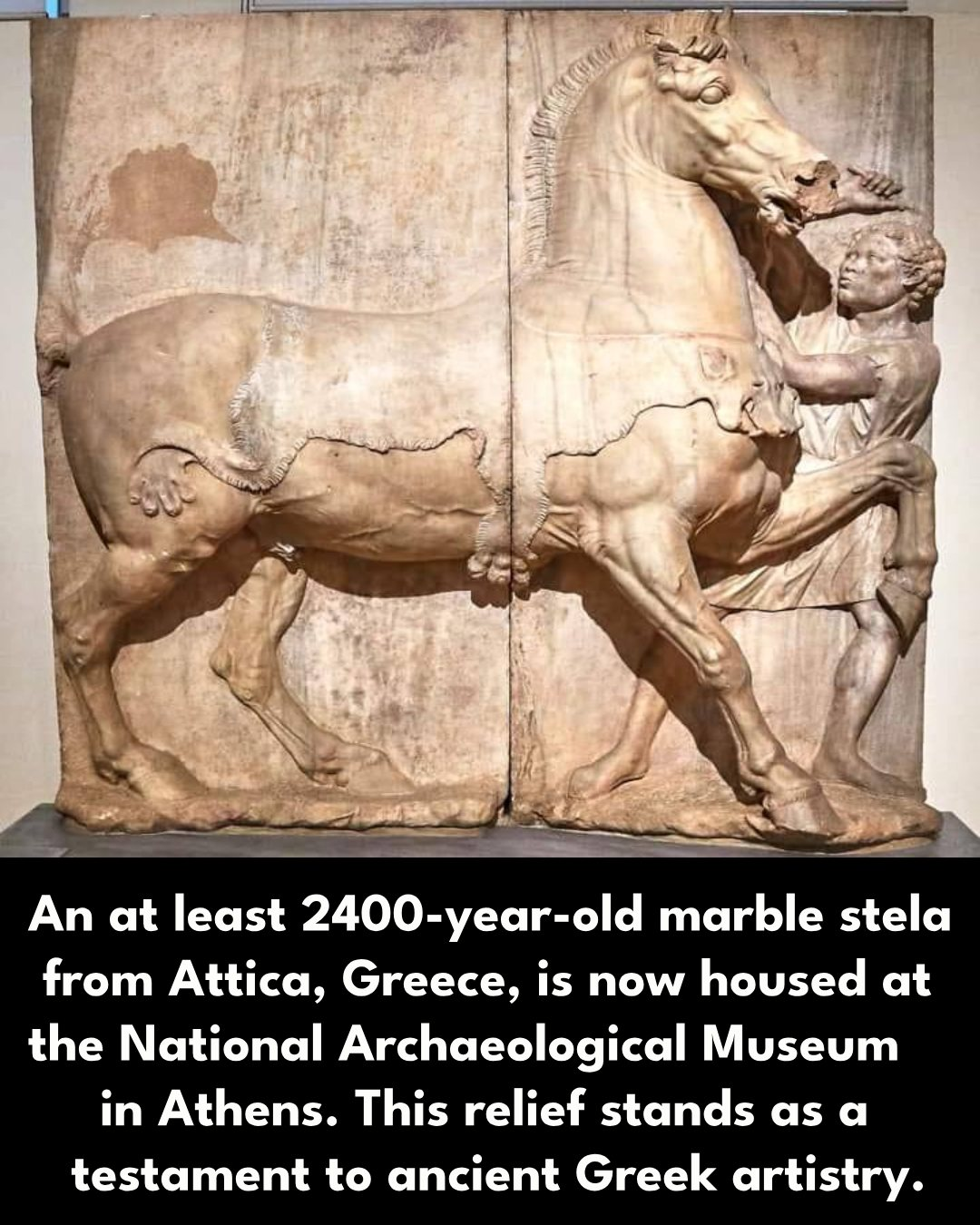

In the hushed galleries of the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, where time itself seems to slow and history whispers from every corridor, there stands a marble relief that arrests the gaze and holds it captive. At first glance, it is simply a boy and a horse—carved in pale stone, frozen in a moment older than most civilizations. But as the eyes linger, something extraordinary begins to unfold. A relationship comes to life—not between man and beast, but between soul and stone, between the living pulse of youth and the eternal stillness of marble.

This is the stele from Attica, carved more than 2400 years ago, a funerary monument from the Classical period of ancient Greece. It may have marked the grave of a noble youth, a warrior perhaps, or the cherished son of a family bound by land, honor, and memory. What remains is not his name, but his likeness—locked in this moment of delicate control, guiding a spirited horse that rears and tosses its head with astonishing vitality. The hand of the boy rests just behind the bridle, calm but firm. His gaze is soft yet resolute. He is no conqueror. He is kin.

To the ancients, the stele was more than a marker. It was a mirror of memory, a way for the living to converse with the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ. In Attica, particularly in Athens during the 4th century BCE, funerary stelae often adorned the cemeteries that lined the roads just beyond the city walls. Each monument told a story—of domestic life, of departure, of valor, or virtue. They were not grand epics carved into cliff sides, but quiet, intimate scenes, like letters written in stone. They were meant not only to honor the departed but to comfort the living.

This particular relief is unlike most. The horse dominates the frame, its musculature rendered with a realism that defies the centuries. Its hooves dance with kinetic energy, its eyes wide and nostrils flared. There is no stillness in its body. The sculptor, whoever he was, had not merely studied anatomy—he had lived with horses, understood them. You can see it in the tension of the animal’s neck, in the sway of its tail, in the way its weight shifts mid-step. This was not just craftsmanship; it was empathy rendered in stone.

And then, the boy. His youth is unmistakable—curly hair, rounded cheeks, a slight frame still growing into adulthood. He wears the himation, a modest cloak draped over the shoulder, indicating neither royalty nor rags. He is of that quiet nobility so prized in Athenian ideals—sophrosyne, the virtue of self-restraint and inner balance. His hand does not yank the reins; it guides. His feet are not planted in dominance but in partnership.

There is something sacred in this dynamic, something eternal. It’s not merely the rider and the ridden. It is a depiction of harmony—man and nature, youth and strength, order and wildness. In ancient Greek philosophy, the horse was often symbolic of the pᴀssions, the unruly elements of the soul that must be tempered by reason. Plato spoke of the charioteer and his two steeds, one noble and one base, forever tugging in different directions. But here, in this marble stele, the boy has no chariot. He has only his hands and his heart. And yet, he prevails.

Archaeologists discovered this stele near one of the burial roads of ancient Attica, likely the Kerameikos—the famed cemetery of Athens. When the marble was unearthed, still carrying the breath of earth and time, it revealed not only art but a worldview. Unlike the grandeur of temples or the rhetoric of political sculpture, this was private. Personal. Meant for mourning, yes—but also for remembering.

We do not know who the boy was. His name is lost, and if there was once an inscription beneath the relief, it has long been worn away by weather and war. Greece, after all, has seen empires rise and fall, each leaving scars across its landscape. Roman conquest, Byzantine rule, Ottoman occupation, modern battles—all have pᴀssed through Athens like tempests. But the marble endured.

It was likely once painted in vibrant color. Ancient Greek sculptures were not the whitewashed relics we see today, but lively images painted with ochre, blues, and reds. The boy’s cloak would have shimmered in sunlight; the horse’s bridle may have been adorned with painted gold. To stand before it in its original form would have been like witnessing a memory come alive, warm with color, trembling with movement.

But even now, stripped of pigment and nestled behind museum glᴀss, the stele sings. Its silence is louder than words. It tells of a youth, remembered not for what he achieved, but for who he was—an image frozen not in glory, but in grace.

Visitors often linger before this stele longer than others. Children seem drawn to the horse, its majesty undeniable even to modern eyes raised on films and fantasy. Adults peer into the boy’s face, searching for something—perhaps recognition, perhaps reflection. Some see in him a son, a brother, a version of themselves from long ago. Others marvel at the sheer artistry, how hands from millennia past could carve so precisely, so humanely.

But all feel something. That is the gift of great art—it bypᴀsses history and theory, and goes straight to the heart.

The boy and his horse are not only Greek. They are human. Universal. They are the distilled essence of youth, bravery, tenderness, and the fleeting beauty of life before it is lost.

In many ways, this relief is a paradox. It was born from death, yet pulses with life. It was meant for mourning, yet inspires awe. It was carved to remember a boy long gone, yet in doing so, it makes him eternal. And perhaps that is why we still create art today—not to fight against death, but to defy it. To whisper, across centuries: “I was here. I mattered. I loved, and I was loved.”

The stele from Attica is not merely a monument. It is a conversation. Between then and now. Between the carver and the viewer. Between the living and the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ.

And in this conversation, we discover not only a forgotten boy and his horse, but also something of ourselves—our longing for connection, our reverence for beauty, and our refusal to let time erase what truly matters.

So next time you find yourself in Athens, in the quiet marble hall of the National Archaeological Museum, pause before this stele. Look at the boy. Look at the horse. And listen.

You may just hear the heartbeat of ancient Greece—still strong, still proud, still whispering across the ages.