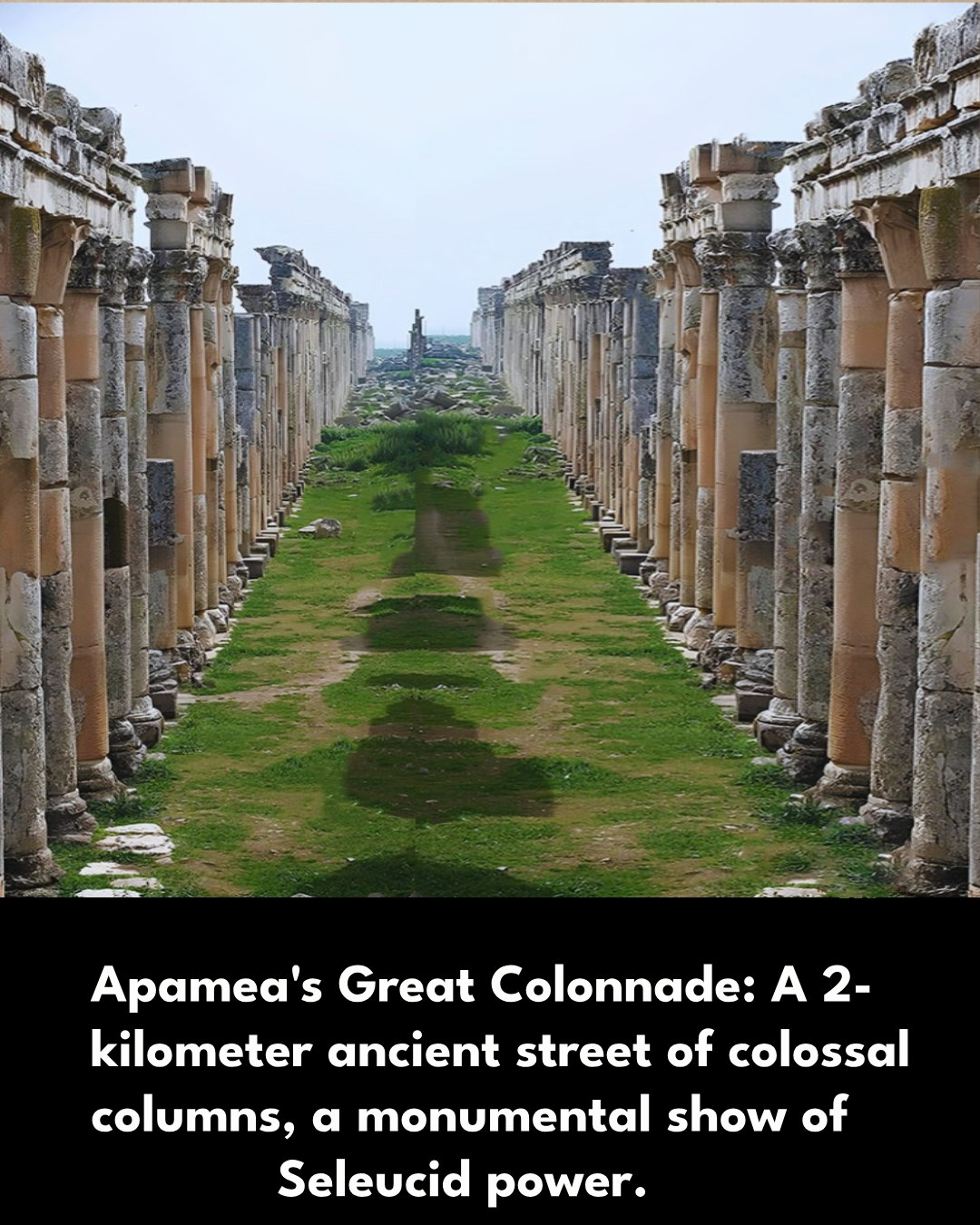

Stretching across the heart of ancient Syria like the spine of a forgotten тιтan, Apamea’s Great Colonnade lies shattered but defiant—a 2-kilometer avenue flanked by more than 1,200 colossal columns. Today, the grᴀss grows between its cracked paving stones, and silence lingers where once sandals clattered and markets roared. But look closely, and you’ll see it still: the grandeur, the ambition, the imperial pride carved into every drum of stone.

This was no ordinary street. This was a declaration.

A parade route for kings.

A forum for philosophers.

A battlefield of ideas and idenтιтy in the vast Seleucid Empire.

Apamea: Where East and West Marched as One

Founded in the 3rd century BCE by Seleucus I Nicator, one of Alexander the Great’s generals, Apamea was more than just a city—it was a statement of Hellenistic might in the Near East. Perched on the Orontes River, it became a vital military base, trade hub, and cultural melting pot, rivaling the great cities of the Mediterranean.

The colonnade was built later, during the Roman period—between the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE—an architectural masterpiece meant to impress not just locals, but gods. Measuring over 37 meters wide in places, the colonnade formed the city’s main axis, lined with shops, baths, temples, and civic buildings. It was one of the longest and most lavish colonnaded streets in the Roman world.

Each column stood as tall as a two-story building, carved from local limestone, topped with Corinthian or Ionic capitals. Together, they formed a marble forest of civilization—linear, ordered, and eternal.

Imagine the processions: imperial legates in red cloaks, Syrian merchants with caravans of incense and glᴀss, priests in white robes calling to distant deities. All beneath these towering guardians of stone.

Earthquakes, Empires, and Erosion

Time, of course, was never kind to empires or their cities.

Apamea endured wars, plagues, invasions, and a series of devastating earthquakes. It pᴀssed from the Seleucids to the Romans, from Byzantines to Islamic caliphates, and finally into ruin. By the 12th century, much of the city was abandoned. Earthquakes split the colonnade like a cracked spine. Statues fell. Marble faded beneath the desert wind.

But it never vanished.

Today, hundreds of columns still stand—or lean defiantly—along the colonnade’s path, casting long shadows over the green-streaked ruins. In some places, sections of the ancient pavement survive, their stones worn smooth by centuries of footsteps, hoofbeats, and wheeled carts.

Archaeologists from around the world come to Apamea to study, restore, and wonder. Each excavation uncovers coins, inscriptions, mosaics, fragments of gods and emperors. Each discovery adds to the puzzle: how did a city so grand fade so completely from public memory?

A Street That Still Speaks

To walk the colonnade of Apamea today is to time-travel. The columns rise like ancient sentinels. The wind moves through them like a breath from the past. There are no crowds, no traffic—only the whisper of history and the echo of ambition.

Apamea reminds us that empires are not only built on conquest, but on vision. That stone can speak louder than scrolls. And that even in ruin, a street can carry the weight of an entire civilization’s pride.

So walk it—slowly.

Let the columns watch you, as they once watched generals and poets. Let the silence tell you stories. Let the dust cling to your shoes like memory.

Because Apamea has not disappeared.

It waits.