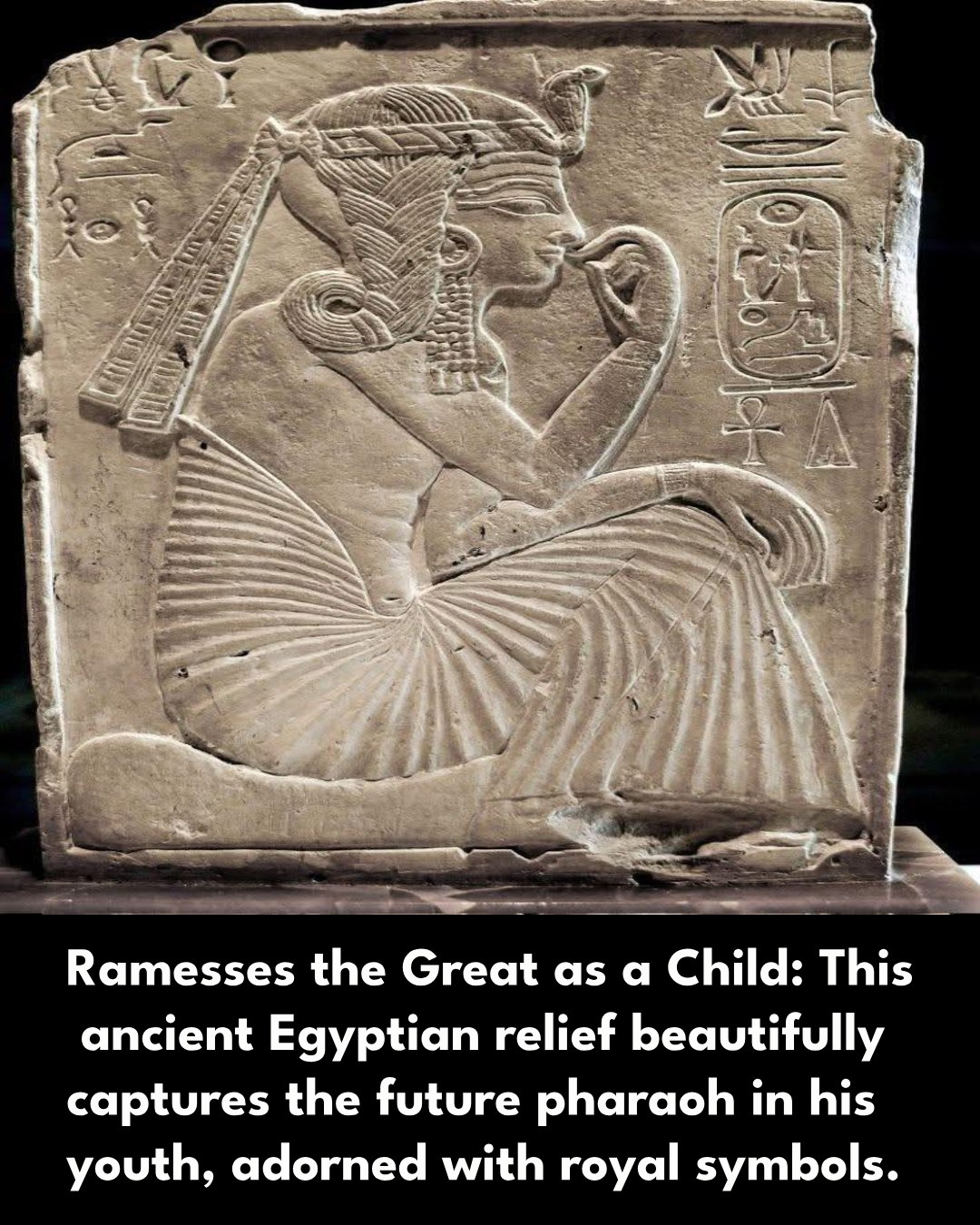

In the stillness of ancient limestone, a story unfolds—not of conquest or coronation, but of innocence. Before he would become a god-king, Ramesses II, the most celebrated pharaoh of Egypt’s long and storied past, was once a child. And here he is—immortalized in this delicate relief, seated, suckling his finger in the traditional pose of divine infancy, adorned already with symbols that would shape an empire.

The craftsmanship is precise, yet tender. The curls of his youthful locks fall with the care of a sculptor who understood not just stone, but destiny. Woven into his hair is the side-lock of youth, a signature symbol in Egyptian iconography for children—especially royal ones. And above his brow, the uraeus cobra, the living emblem of sovereignty, vigilance, and divine protection, already marks him as chosen. This child was no ordinary boy; he was born under the gaze of gods, trained not just for rule, but for eternity.

Hieroglyphs flank him like whispers from the past—his cartouche enclosing his birth name, perhaps paired with тιтles even in youth. The presence of the ankh, the symbol of life, suggests more than biological growth—it speaks of divine essence, of a breath granted by the gods themselves. The flared pleats of his garment, fanned around him like a lotus, give him the poise of a young god in repose, waiting only for time to unfold.

Ramesses the Great, who would go on to rule for 67 years during the 13th century BCE, was a тιтan among kings. He built vast temples, expanded Egypt’s borders, signed the world’s earliest known peace treaty, and carved his likeness into cliffs to defy oblivion. Yet this small relief captures something far more precious than his grandeur—it captures his humanity. A boy, perhaps no older than five or six, unaware of the weight of the crown he would someday bear.

There is something deeply moving in this depiction. We are so often taught to view pharaohs as remote тιтans, larger than life, wrapped in linen and legend. But here, in this moment of stone stillness, we see the child beneath the crown—the breath before the reign, the heartbeat before history. He is not yet a warrior. Not yet a builder of cities. He is simply becoming.

The ancient Egyptians believed that kings were divine not because they conquered, but because they were born into cosmic order, reflections of Ma’at—the harmony of the universe. This relief, then, is not just art. It is theology. It reminds the viewer that even gods must begin as children. That all greatness begins in small, sacred stillness.

And perhaps that is the most enduring lesson of this stone: that even the greatest figures in history were once vulnerable, uncertain, hopeful. That destiny starts in silence—etched quietly into the stone, waiting to be remembered.