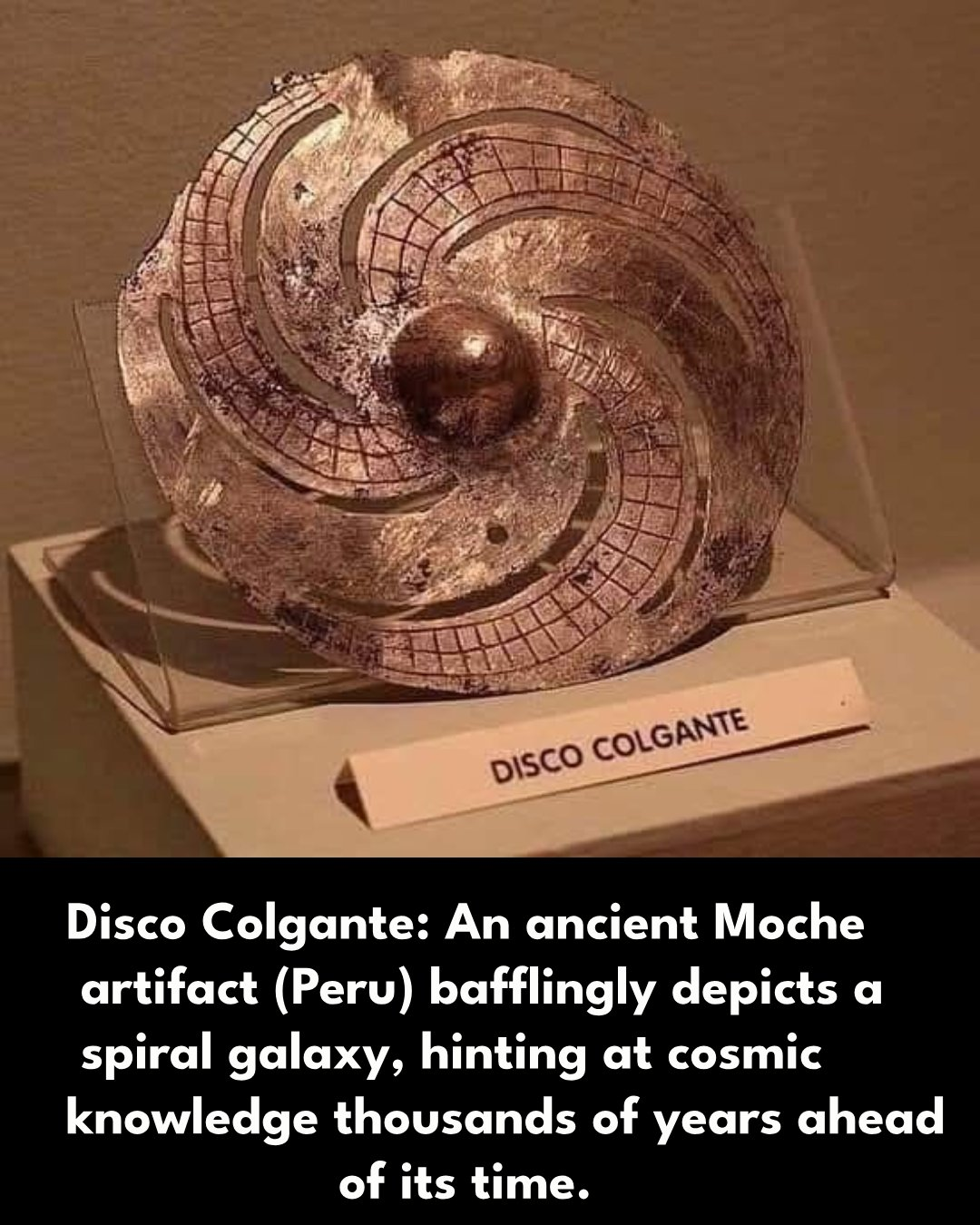

In the hushed galleries of a Peruvian museum, among the golden masks and intricate ceramics of a long-vanished culture, rests a disk that stares back at us like an ancient riddle. Labeled simply “Disco Colgante”—“Hanging Disk”—this artifact gleams with coppery age, its surface etched in a swirling design uncannily reminiscent of a spiral galaxy. With its precise curves and suggestive center, it evokes the swirling arms of the Milky Way—a symbol of cosmic structure carved millennia before Galileo peered through his telescope.

And the question echoes across time: How did they know?

The Moche civilization flourished on the northern coast of Peru between 100 and 700 CE, long before telescopic astronomy, orbital theory, or any known exposure to images of spiral galaxies. Their art is renowned for its realism and symbolism—depicting gods, warriors, ceremonies, even surgical procedures—but nothing among their thousands of documented artifacts quite matches the cosmic curiosity of the Disco Colgante.

The spiral design appears intentional. Four curved arms radiate from a central sphere, their paths traced with linear markings that suggest movement, or perhaps division—like the quantified arms of a celestial body. It resembles not only the Milky Way, but other barred-spiral galaxies discovered with modern imaging. The disk’s symmetry is almost scientific, its elegance timeless. And yet, it was created by people whose astronomy, as we understand it, was based on naked-eye observations of the sun, moon, and planets.

Was this truly a representation of the galaxy? Or does our modern gaze simply see a galaxy in its form—projecting cosmic knowledge backward through time?

It’s tempting, of course, to leap to ancient astronaut theories or advanced prehistoric science, especially in an age where mystery often blurs with myth. But such leaps often do disservice to the true genius of ancient civilizations. The Moche, like many Andean peoples, held a deep relationship with the cosmos. Their rituals aligned with solstices and lunar phases. Their pyramid structures mirrored celestial cycles. Spirals in their iconography symbolized life, death, water, fertility, and time. The whirlpool of the heavens, after all, has always been visible to the naked eye as the band of the Milky Way twisting across the night sky.

Perhaps what we call “cosmic knowledge” was, to them, spiritual memory.

The central dome of the disk may symbolize a sun, a black hole, or even the navel of the universe—the axis mundi around which life spins. The spiral, a sacred motif in cultures from Celtic to Polynesian, often represents a pathway to the divine. Seen this way, the Disco Colgante is not a scientific diagram, but a spiritual cosmogram. A map of metaphysical order. A wearable testament to the interconnectedness of all things.

Its name—Colgante—suggests it was worn, perhaps by a priest, a shaman, or a ruler, its power not just aesthetic but symbolic. Imagine a figure standing at the heart of a Moche temple, sunlight glinting off this disk as chants filled the air. It wasn’t just decoration. It was declaration—of harmony between earth and stars, between knowledge and mystery.

Even so, the allure remains. The disk whispers of a greater understanding, hinting at truths our own civilization still struggles to grasp. Whether metaphor or map, the Disco Colgante reminds us that the ancients did not look up with ignorance—but with wonder. With questions. With visions.

And perhaps that’s the real lesson. That human beings, regardless of era, have always yearned to understand their place in the vast spiral of existence.

Was it a galaxy? A symbol? A miracle of intuition?

Or was it—like all great art—something more?

A mirror. Reflecting back the mystery of the cosmos in the language of metal and myth.