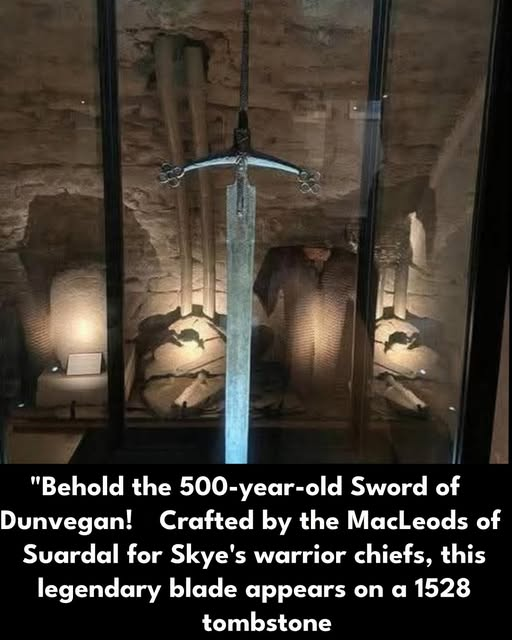

The Isle of Skye is not merely a land—it is a legend. Shrouded in the mists of the Hebrides, its rugged cliffs and brooding skies speak of old gods, of sea-worn stones, and of warriors who once carved their names into time with steel and fire. Among Skye’s many relics, none resonates quite like the ancient Sword of Dunvegan—a 500-year-old Highland blade, tall as a man and weighty with myth, still gleaming faintly beneath the dim lights of a museum vault.

It is not just a sword. It is a survivor.

Forged in the early 16th century, this greatsword belonged to the MacLeods of Suardal, a powerful branch of Clan MacLeod—chieftains of the Isle of Skye. Their stronghold, Dunvegan Castle, is the oldest continuously inhabited castle in Scotland. It is a place where memory clings to the stone walls like the scent of peat smoke, and the echoes of clan battles still seem to stir in the heather.

The Sword and the Stone

The blade first reveals itself not in battle, but in death. It appears etched into a sandstone tomb slab dated 1528—a solemn outline above the figure of a warrior chief, hands clasped in prayer, armor dulled by centuries of time. The tomb lies in the ruined church of Trumpan, not far from the MacLeod lands. There, among weather-worn gravestones and sea-lashed ruins, the sword’s silhouette offers the earliest known image of this very weapon.

Archaeologists studying the tomb were struck not just by the sword’s depiction, but by its scale and design. It is a true Highland claymore—broad-bladed, cross-hilted, with quillons turned slightly downward and a rounded pommel. Such swords were symbols of power, wielded by clan leaders during the turbulent years when the Highlands were a land apart—untamed, Gaelic-speaking, and fiercely loyal to kin.

When the real sword was rediscovered centuries later in the armory of Dunvegan Castle, historians realized something rare had happened: an object once immortalized in stone had physically endured the centuries. It was no mere ceremonial replica. This was the blade.

Forged in a Fractured World

To understand the sword, one must understand the world that gave birth to it. In the early 1500s, Scotland was a land divided—not only between Highlands and Lowlands, but between kings and clans, crown and croft. The MacLeods of Skye stood among the most powerful families in the Hebrides, ruling vast tracts of sea and land, where Norse and Celtic traditions still held sway.

It was an age of betrayal and blood-oaths. Clans warred over pastureland, fishing rights, and old feuds handed down like heirlooms. Swords were not ornamental—they were law, status, survival. When a MacLeod chief raised this sword, it was not only to defend territory—it was to invoke centuries of ancestry, to remind enemies and allies alike that he was a descendant of kings.

The MacLeods’ forge at Suardal was a sacred place, said to be built near a Viking smithy. Local legend claims that the swordsmith who made this blade had once been a hostage in Norway and returned to Skye with secrets of Norse ironwork. The steel he used was folded and quenched with bog water—a Highland tradition that infused the blade with strength, and, some whispered, a ghost of the land itself.

The sword bore no inscriptions, no runes or names. It didn’t need them. Its weight spoke for itself. Its presence was language.

The Hands That Held It

Though no single warrior can be confirmed as its first master, clan records suggest it likely belonged to Alasdair Crotach MacLeod, the 8th Chief of Dunvegan, whose reign spanned the turbulent early 1500s. Alasdair was a warrior, but also a patron of the church and the arts—his tomb is the very slab where the sword is carved.

His nickname, Crotach, meaning “humpbacked,” came after he was wounded in battle, possibly fighting the rival MacDonalds of Uist. His back curved, but his spirit did not. He commissioned churches, protected poets, and held fiercely to his land even as clan power began to wane in the face of growing royal authority from Edinburgh.

If the sword was indeed his, it would have witnessed raids on the Isle of Harris, defenses of Dunvegan’s stone walls, and perhaps even the savage Battle of the Spoiling Dyke, when MacLeod women and children were mᴀssacred by MacDonald raiders at Trumpan Church. Legend says the MacLeods took brutal vengeance the next day, slaughtering every MacDonald on the island. The sword may have sung then—its steel wet with the salt of Skye’s storms and the blood of its enemies.

From War to Reverence

By the 17th century, muskets and pikes had begun to replace broadswords in Highland warfare. The claymore became ceremonial—a relic of a proud but fading warrior code. Still, the Sword of Dunvegan was preserved, pᴀssed from chief to chief like a sacred relic.

In time, it moved from the battlefield to the banquet hall, hung behind the great fireplace of Dunvegan Castle’s drawing room, where visiting nobles and poets would ask its history. To touch the sword was to be blessed by old honor. To carry it in processions was to walk in the shadow of giants.

But as centuries pᴀssed, even the castle walls could not stop time. The Highlands were pacified. The clans, broken by the Jacobite uprisings and the clearances that followed, faded into memory. Gaelic gave way to English. The sword was no longer a weapon—it was a question: Who were we?

The Ghost in the Glᴀss

Today, the sword rests in a climate-controlled display case—cold and still, but never silent. Visitors to the museum stand before it, struck by its size and simplicity. There are no jewels, no filigree. Just iron, leather, and the quiet weight of history.

Some see only a sword. Others see something more: the hands that gripped it, the arms that swung it, the breathless seconds before battle when death hung between two men like a prayer. They see the land—Skye’s black cliffs, its storm-lashed beaches, its heather-burning winters—and the people who carved meaning into their lives through struggle, survival, and steel.

For those who listen closely, the blade still hums. Not with violence, but with memory.

What Remains

The Sword of Dunvegan is more than an artifact. It is a mirror held up to the Highland soul. It speaks of loyalty and vengeance, of clan pride and human frailty, of warriors who were not just fighters, but fathers, builders, dreamers. It reminds us that history is not only written in books, but etched into the objects we leave behind.

You might wonder: how can something forged to kill now live on to inspire?

Perhaps because in its silence, it tells us something enduring—that even in a world of fleeting lives and lost battles, the things we hold with honor can outlive us.

And when we gaze upon it, standing tall beneath the flickering museum light, we are not just looking at a sword. We are looking at the last breath of a world that once believed courage could be held in the hand.

Would you lift it, if you could?

Would your heart know how to carry what it once meant?