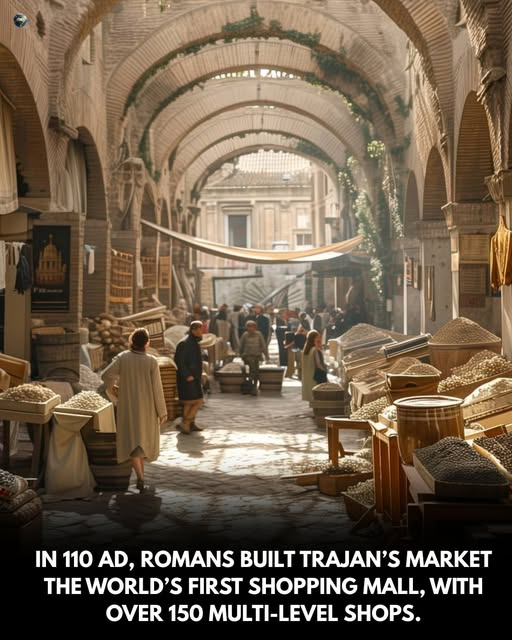

In the heart of Imperial Rome, where emperors plotted destinies and legions marched to shape the world, there once stood a place that pulsed not with war, but with commerce, chatter, and the scent of saffron and spices. It wasn’t a temple, nor a palace—it was a market. But not just any market. Built around 110 AD under the watchful eye of Emperor Trajan, this was Mercatus Traiani—Trajan’s Market—the world’s first known shopping mall. And in the shadow of Rome’s mighty forums, it offered something as revolutionary as roads or aqueducts: the organized, multi-level pleasure of browsing.

Today, its arches and vaults still whisper stories, echoing the footfalls of sandals on marble, the bark of traders hawking Syrian silk or Egyptian glᴀss, the hum of daily Roman life. Archaeologists call it an architectural marvel. Historians call it a symbol of imperial ingenuity. But if you asked a Roman citizen of the second century, they’d likely say it was where you went to find everything.

Trajan’s Market was part of a larger project—an ambitious overhaul of the Roman Forum designed to glorify the Emperor Trajan’s victories, especially over the Dacians. The project included the mᴀssive Trajan’s Column, the grand basilica, and the forum itself. But nestled against the Quirinal Hill, carved partly into the living rock, the market served a different purpose: to serve the people.

Built by the master architect Apollodorus of Damascus, the market was a vertical city of trade, carved into six tiers that curved like a half-moon. From the street-level tabernae (shops) selling wine, oils, and garum (Rome’s favorite fermented fish sauce), to the upper-level administrative offices and terrace views of the city, Trajan’s Market was a Roman dream of order, convenience, and spectacle.

Imagine walking through its great corridor, bathed in warm light filtering through high archways. Vendors called out in Latin, Greek, and Aramaic. You’d smell cumin, cinnamon, and fresh bread. Tactile textures surrounded you—soft Syrian linens, cool amphorae, rough baskets of olives. Stone pillars towered like trees in a forest of commerce. And above all, the sound: a symphony of footsteps, coin clinks, laughter, and argument.

Here, Rome came alive—not in conquest, but in connection.

It’s easy to forget that ancient people needed the same things we do: shoes, fruit, furniture, fabrics. And in this vast complex of over 150 shops, the Roman consumer found it all. But more than that, Trajan’s Market was a hub of daily life. There were legal offices, government archives, lecture spaces, and even food courts. Yes—Rome had food courts.

Bread counters served warm loaves for a sesterce or two. Taverns ladled H๏τ lentil stew. You could find mulled wine, salted fish, and fresh fruit imported from North Africa. And amid all this bustle, deals were made, gossip traded, and politics debated.

One can imagine a Roman woman, cloaked in fine wool, bartering over Phoenician dye. A former soldier limping past jars of ointments. A Greek philosopher buying scrolls from a traveling scribe. The market became not only an economic center but a cultural crossroad—an empire’s diversity in miniature.

Yet as much as it was functional, Trajan’s Market was also symbolic. It said something profound about Rome’s vision. This was not just a place to buy goods—it was an engineered statement of power, prosperity, and permanence. Built in brick and concrete, adorned with marble and stucco, it defied earthquakes and time.

It was the Empire in stone: layered, structured, expansive, and efficient. In some ways, Trajan’s Market was Rome’s quiet promise—that its golden age wasn’t only about triumph, but about sustainability, about infrastructure that served its citizens.

The genius of the market lies not only in its scale but in its layout. The semi-circular design allowed for optimal use of space and sunlight. The covered hall—now called the Great Hall—was ventilated by cleverly placed windows. Rainwater was collected and channeled. The shops were uniform in size, tiled for hygiene, and operated under imperial regulations. Even shopping, it seems, was part of Roman order.

Centuries pᴀssed. The Western Roman Empire fell. The market, once a hub of voices and footsteps, fell silent. Over time it was repurposed: a fortress in the medieval era, a monastery in the Renaissance. Layers of history accumulated like sediment, burying Trajan’s Market beneath newer cities and newer empires. Yet it remained, patient beneath the dust.

It wasn’t until the late 20th century that major restoration efforts peeled back those layers. Archaeologists walked the same hallways as the Roman shopper once did. Stone counters still bore grooves from scales and weights. Drainage systems still whispered of Roman engineering. Inscriptions emerged, naming shopkeepers long forgotten. And thus, the market came back to life—not as a commercial center, but as a testament.

What draws us to places like this? Why does a ruin of ancient brick and mortar still captivate the modern mind?

Perhaps it’s because Trajan’s Market makes the ancient intimate. While temples and theaters speak of gods and heroes, the market speaks of people. Here was where a mother bought fabric for her children. Where two old friends shared olives and laughter. Where a young trader nervously opened his first stall. It wasn’t history written in stone—it was life pressed into the dust of daily routine.

In a world that often venerates the grand and the exceptional, Trajan’s Market reminds us that civilization is built not just by emperors and armies, but by shopkeepers, merchants, and ordinary dreams exchanged in coins.

Even now, walking through its arches as a tourist, you feel time shift. Light dances across ancient stone. Footsteps echo where legionaries once lingered. You see the shadows of togas and tunics. And you feel, strangely, at home.

Because in the end, this place was always about connection. It was about people coming together—in trade, in dialogue, in the small rituals of daily life. That spirit endures, not in the goods that were bought and sold, but in the spaces that invited exchange.

Trajan’s Market is not just a relic. It is a living echo—a whisper that says:

Before you had supermarkets, we had this.

Before you filled malls with glᴀss and steel, we filled arches with life.

Before you dreamed of convenience, we built it in stone.

And still it stands, quietly alive beneath Rome’s eternal sun.