Archaeologists have uncovered new evidence that ancient human communities in western Iran, over 11,000 years ago, were engaging in grand feasting rituals with wild animals transported from far-off places, well before the dawn of agriculture. The research, published in Communications Earth & Environment, is centered around discoveries at the Early Neolithic site of Asiab in the Zagros Mountains.

11,000-year-old feast in Iran’s Zagros Mountains reveals long-distance animal transport and early Neolithic social rituals

11,000-year-old feast in Iran’s Zagros Mountains reveals long-distance animal transport and early Neolithic social rituals

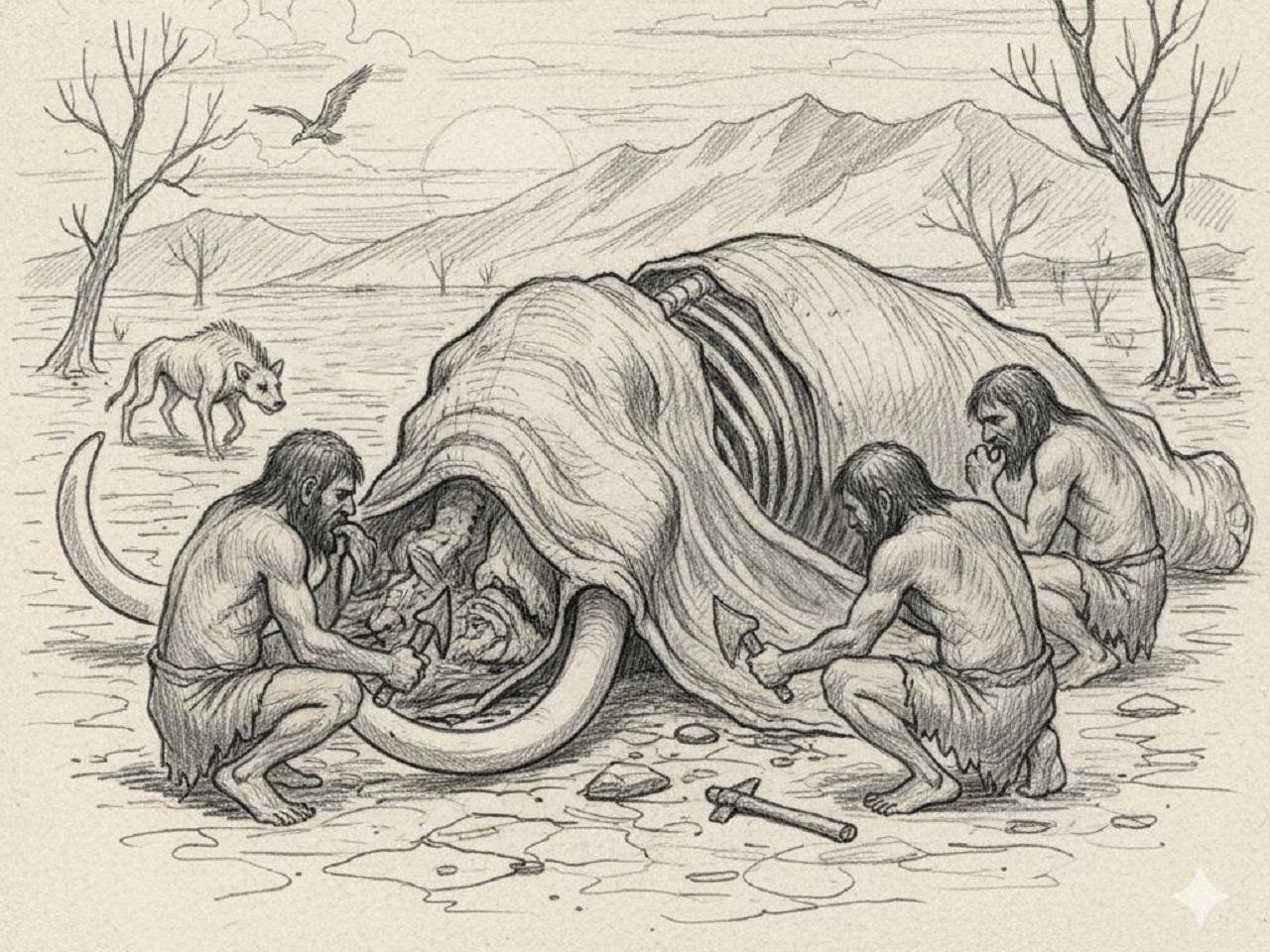

Excavations at Asiab revealed the skeletons of 19 wild boars, slaughtered and buried together in a pit within a circular semi-subterranean building approximately 20 meters in diameter. This structure, which is believed to have served as a communal gathering place, was likely the site of a single large-scale ceremonial feast. Along with the skeletons of the boars, researchers also found brown bear bones and red deer antlers, suggesting a broader ritual context.

What makes this discovery unique is the new understanding of the origin of the animals used in the feast. The researchers used microscopic analysis of tooth enamel, which forms in daily layers like tree rings, to determine where the animals came from. By combining enamel growth patterns with advanced geochemical techniques, including oxygen and strontium isotope analysis and barium mapping, they were able to trace the animals’ movements throughout their lifetimes.

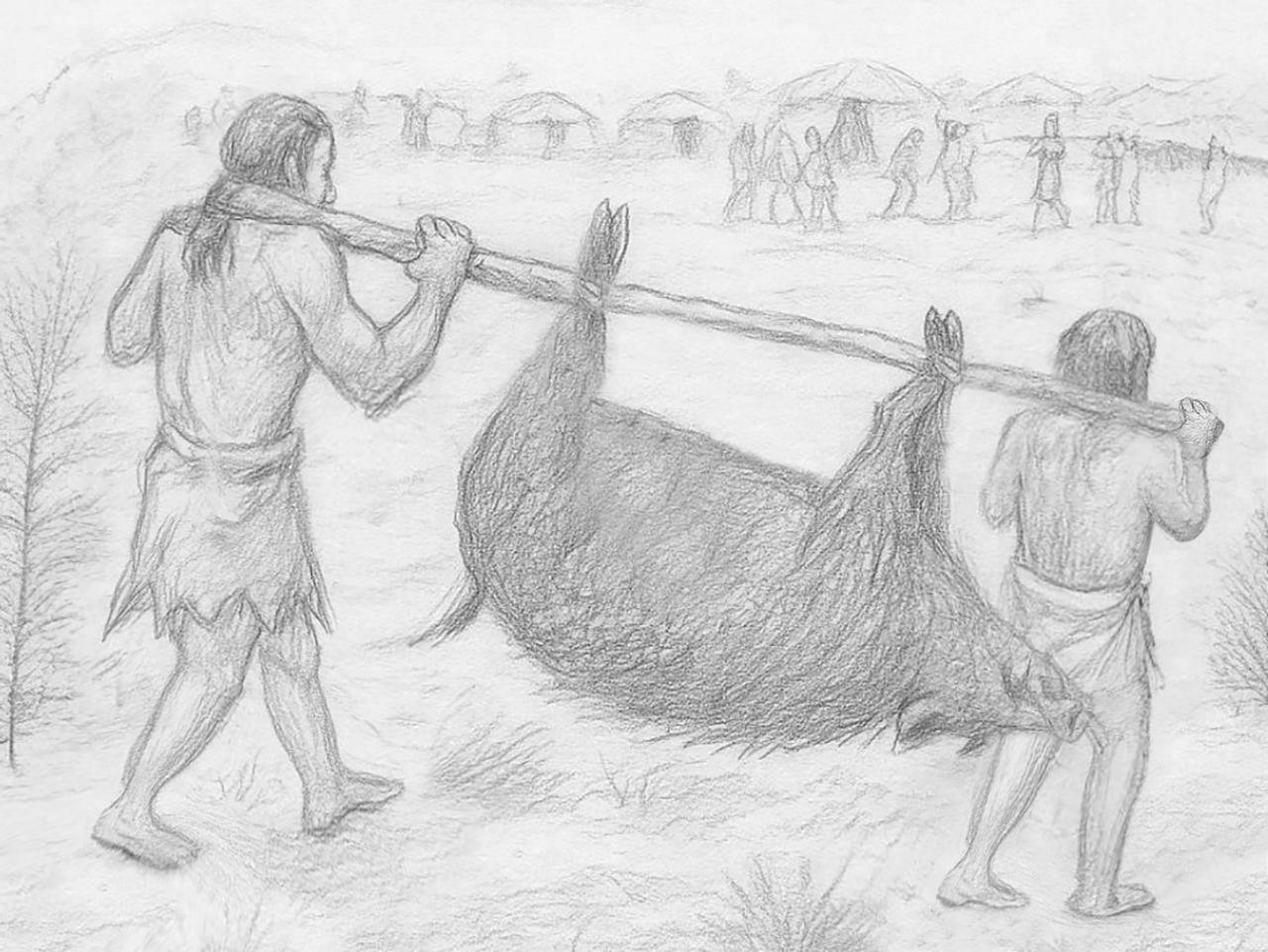

Although the region appears to be well suited to wild boars, isotopic analysis revealed that some of the animals had been moved from as far away as 70 kilometers. Transporting these animals over such hilly country would have required a deliberate and significant effort.

Clay figurine of a wild boar, Neolithic period. Found at Tepe Sarab, Iran. Credit: National Museum of Iran / CC BY-SA 4.0

Clay figurine of a wild boar, Neolithic period. Found at Tepe Sarab, Iran. Credit: National Museum of Iran / CC BY-SA 4.0

Feasting, as researchers believe, was not merely the consumption of food—rather, it was a means of forging and reaffirming social ties. The yield of meat, approximately 700 kilograms as estimated by researchers, could have fed 350 to 1,200 people, many more than a typical Epipaleolithic settlement. This suggests the potential that the event was a mᴀss gathering or that the meat was used ritually, for more than consumption, perhaps even sacrifice.

What makes the Asiab results particularly significant is that they push the date back for these sophisticated social practices to a pre-agricultural, pre-domestication period. While such extensive transport of foodstuffs has been documented at later sites such as Stonehenge, this is the first known instance from a pre-agricultural context.

The Asiab feast reflects an elaborate system of social relations and shared cultural practices that extended across landscapes. As far as the researchers can tell, the symbolic act of collecting distant animals for communal feasting might have contributed to the fostering of the kinds of reciprocal relationships that eventually supported more permanent, agricultural societies.

More information: The ConversationPublication: Vaiglova, P., Kierdorf, H., Witzel, C. et al.(2025). Transport of animals underpinned ritual feasting at the onset of the Neolithic in southwestern Asia. Commun Earth Environ 6, 519. doi:10.1038/s43247-025-02501-z