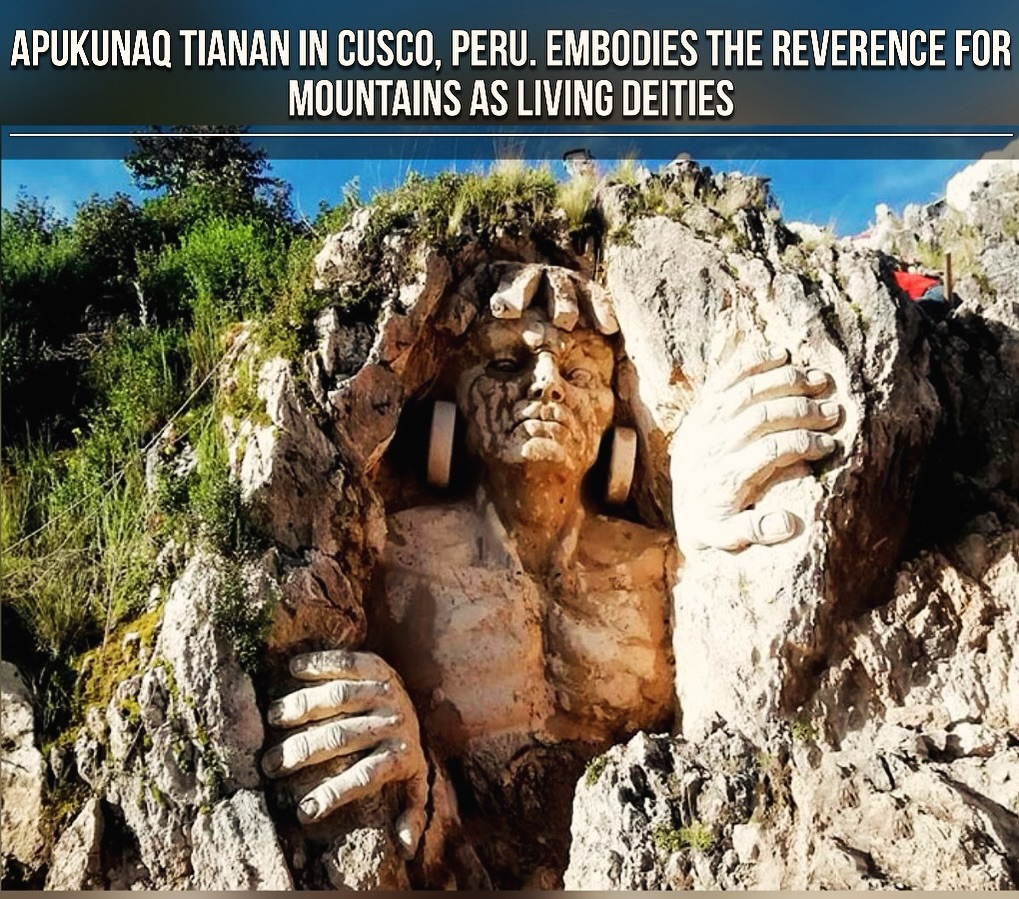

High above the Sacred Valley of the Incas, where the breath of the mountains mingles with the sky, a colossal figure emerges from the rock itself—part sculpture, part myth, wholly sacred. This is Apukunaq Tianan, “The Abode of the Gods,” a monumental tribute to the Andean belief that mountains are not simply stone—they are alive, watching, guiding, and protecting. Here in Cusco, Peru, the heart of an ancient empire, the old spirits breathe again, not in whispers but in carved majesty.

Created by Peruvian artist Michael de тιтan, the immense stone figure is not an ancient ruin but a modern homage to ancestral wisdom, completed in the early 21st century. Yet everything about Apukunaq Tianan feels timeless. The figure’s face is weathered and wise, with hands pushing through the jagged mountain as though the earth itself were birthing a god. At once emerging and eternal, the sculpture becomes a threshold—between past and present, myth and matter, human and divine.

In the Quechua tradition, “Apus” are sacred mountain spirits—sentient guardians of the land. Each peak has its own Apu, its own voice, its own personality. The Incas built shrines to these spirits, left offerings of coca leaves, chicha, and prayers, asking for protection, rain, and guidance. To walk through the Andes was never to walk alone—it was to move among living ancestors, whose bones were cliffs, whose breath was mist, whose gaze came from the stars.

Apukunaq Tianan channels this reverence into form. The stone guardian doesn’t speak, but its silence echoes louder than words. Children point. Elders nod. Tourists stand transfixed. Something in those carved eyes reflects not only ancient spirituality but our shared human yearning—for connection, for meaning, for permanence in a fleeting world. This isn’t just a sculpture. It’s a return.

Today, the site has become a pilgrimage—not just for worship, but for wonder. Modern Peruvians and international travelers alike trek the paths of their ancestors, seeking the same clarity, the same communion. The mountain receives them all with open arms, as if saying: “You were always part of this.”

What does it mean, in our fractured modern lives, to remember that the land has a soul? That the mountains are watching? That we, too, are stories written in stone?

Apukunaq Tianan doesn’t offer an answer. It offers presence.

And perhaps that is enough.

<ʙuттon class="text-token-text-secondary hover:bg-token-bg-secondary rounded-lg" aria-label="Chia sẻ" aria-selected="false" data-state="closed">