Archaeologists in northeastern Italy have discovered a remarkable find in a well near Faenza, close to Ravenna: the highly degraded remains of an infant who lived 4,000 to 5,000 years ago and belonged to the Copper Age. Although the skeleton had been reduced to just a few dental crowns and tiny pieces of bone, a team led by researchers from the University of Bologna managed to reconstruct important aspects of the infant’s life, health, and ancestry using advanced scientific methods.

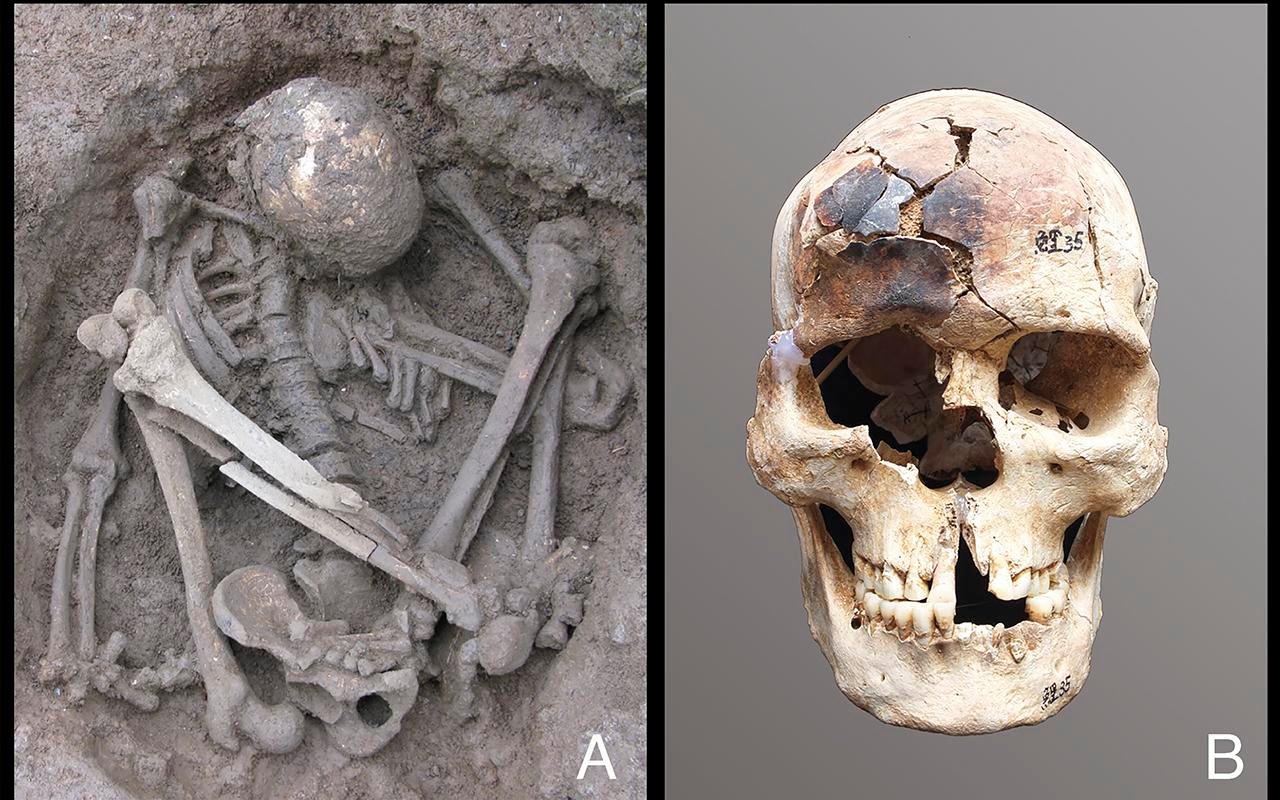

Close-up of the Copper Age infant’s remains in situ. Credit: Ministry of Culture – Superintendence of Archaeology, Fine Arts, and Landscape for the provinces of Ravenna, Forlì-Cesena, and Rimini

Close-up of the Copper Age infant’s remains in situ. Credit: Ministry of Culture – Superintendence of Archaeology, Fine Arts, and Landscape for the provinces of Ravenna, Forlì-Cesena, and Rimini

The excavation was carried out during a routine archaeological survey before a construction project. Traditional osteological analysis yielded little data due to the severely degraded state of the remains. Scientists therefore resorted to an interdisciplinary approach and employed dental histology, radiocarbon dating, biogeochemistry, paleoproteomics, and ancient DNA (aDNA) techniques to determine as much as they could.

Lead author Owen Alexander Higgins, a research fellow at the Department of Cultural Heritage at the University of Bologna, highlighted the significance of even the most degraded remains. He said “Our research shows that even highly degraded osteological materials hold important information if examined using advanced methods.”

Using microscopic analysis of two teeth—a baby molar and a developing permanent molar—scientists were able to estimate that the child had pᴀssed away at around 17 months of age. Histological analysis revealed no sign of malnutrition or stress in early development, indicating that the child had enjoyed a relatively good start to life.

Overview of the excavation unit with ᴀssociated artifacts visible. Credit: Ministry of Culture – Superintendence of Archaeology, Fine Arts, and Landscape for the provinces of Ravenna, Forlì-Cesena, and Rimini

Overview of the excavation unit with ᴀssociated artifacts visible. Credit: Ministry of Culture – Superintendence of Archaeology, Fine Arts, and Landscape for the provinces of Ravenna, Forlì-Cesena, and Rimini

It was hard to determine the Sєx of the child due to the fragmentary nature of the remains. However, both proteomic analysis of the dental enamel and genomic examination of the bone fragments confirmed that the infant was male. According to the researchers, the analysis of ancient DNA identified a rare mitochondrial haplogroup, V+@72, which has been discovered in only one other ancient sample from the Eneolithic necropolis of Serra Cabriles in northwestern Sardinia.

This maternally derived haplogroup is extremely rare in modern European populations and is predominantly ᴀssociated with the Saami of northern Europe and populations along the Cantabrian coast in Spain. Its presence in Copper Age Italy signals possible long-distance maternal connections and suggests undocumented prehistoric migrations or cultural interactions in prehistoric Europe.

Views of the deciduous upper right first molar (URdm1) and the permanent lower right first molar (LRM1) selected for histological analysis. Credit: O. A. Higgins et al., Journal of Archaeological Science (2025)

Views of the deciduous upper right first molar (URdm1) and the permanent lower right first molar (LRM1) selected for histological analysis. Credit: O. A. Higgins et al., Journal of Archaeological Science (2025)

The research, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, was conducted by researchers from nine insтιтutions, including the Max Planck Insтιтute for Evolutionary Anthropology and Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. The researchers unveiled how poorly preserved remains could uncover information about ancient life and the movement and connections of prehistoric Europeans.

Far from being merely another forgotten burial, the baby from Faenza is now a strong testament to the ways in which science can breathe life into tales from the distant past.

More information: Higgins, O. A., Fontani, F., Lugli, F., Silvestrini, S., Vazzana, A., Latorre, A., … Benazzi, S. (2025). Reconstructing life history and ancestry from poorly preserved skeletal remains: A bioanthropological study of a Copper Age infant from Faenza (RA, Italy). Journal of Archaeological Science, 180(106291), 106291. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2025.106291