Christopher Nolan’s The Odyssey will see the director take on one of the most enduring and beloved tales of all time. It’s also his follow-up to Oppenheimer, which won seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Supporting Actor, and Best Original Score. Each drip of information about the movie – from the casting of Matt Damon as Odysseus to leaked pH๏τos of Tom Holland sporting ancient Greek armor – has made the rounds on the internet, proving that the movie has an atomic bomb-sized crater to fill.

Nolan is one of the most celebrated directors of the modern era, but The Odyssey is a difficult story to adapt. And Gregory Nagy, Francis Jones Professor of Classical Greek Literature and Comparative Literature at Harvard University, knows why. The professor has devoted his life to understanding and teaching the epic poem and its predecessor, The Iliad, and he is an expert on how early audiences understood the story of the Trojan War and Odysseus’ return from it.

ScreenRant interviewed Gregory Nagy about his thoughts on a film adaptation of The Odyssey. The professor and scholar explained the very different context in which the story was originally told, what he thinks about the casting of Matt Damon as Odysseus, and what aspects of the character likely won’t make it to the big screen. Plus, Nagy shared his thoughts on 2004’s Troy and the advice he’d give to any filmmaker taking on the Homeric epic.

Gregory Nagy Explains Why The Odyssey As A Blockbuster Is “Pretty Far” From The Story’s Intent

The Odyssey Is More About “The Workings Of The Cosmos”

At first glance, The Odyssey is perfect for the big-budget blockbuster treatment. Odysseus encounters monsters on land and sea, finds himself in thrall to gods and witches, and saves his family from death in an overwhelming display of strength – all while reckoning with the trauma of war and his longing for those he left behind. But in many ways, condensing a roughly 12,000-plus line poem into a three-ish-hour movie that follows modern storytelling conventions is an incredibly tall order – and not one the story was designed for.

“In the ancient world,” Harvard professor Gregory Nagy began, “what we think of as plot is very different.” He shared that one “can’t even deal with traditional myth without thinking of the traditional society that generated the myth.” In that context, the professor stated that making The Odyssey a spectacle designed to thrill movie-going audiences is “probably pretty far” from the narrative’s original intent, even if “what almost everybody can agree on is that it’s a very good narrative.”

“Imagine a situation where a traditional society has a view of the cosmos … this tells [us] about the workings of [it.]”

In Nagy’s estimate, The Odyssey evolved sometime around the “early seventh century B.C.E.” which is roughly 2,700 years ago (“There’s no technology or writing in the making of any of this,” Nagy pointed out). And to the professor, The Odyssey wasn’t even initially told to be a “story” in the way we understand it: “I’ll say ‘narrative’, because if we say ‘story’, it’s something that we don’t have to accept as truth.” Instead of simply being entertainment, The Odyssey was meant to help people understand the world around them. “Imagine a situation where a traditional society has a view of the cosmos … this tells [us] about the workings of [it.]”

“Okay, Fine”: Nagy’s Thoughts On Matt Damon As Odysseus

Plus, The Professor Shares Insights Into The Character

When you think about the driving forces behind the natural world, you (probably) don’t think of Matt Damon. But the Good Will Hunting star is set to take on the role, and is front and center in the first official still released from the movie. When told that Damon would take the starring role in the film, Nagy had a quick response: “Okay, fine.”

Even if he believes Damon is up for the challenge, Nagy said, “The character of Odysseus is very complex.” He pointed out one interesting challenge about the scope of the story, specifically about the character’s return to his homeland: “Odysseus is 20 years away from home in terms of the narrative,” Nagy said, referring to the fact that, in the narrative, Odysseus fought at Troy for 10 years, then spent another 10 returning home. “That would make him middle-aged, or even on the side of older age. And, similarly, Penelope would be getting along in years too.”

“And yet, it’s very important in the Odyssey as I study it,” said Nagy, “that when Odysseus gets back together with Penelope, he becomes so good-looking that he looks like a 20-year-old bridegroom, and even his son says, ‘Wow, Dad. I can’t believe it.’ He looks like the sun, practically. There’s so much cosmic intervention.” For those who don’t know the tale, Odysseus disguises himself once he finally returns to his homeland to reclaim it so that he can understand who is loyal to him and who is a threat – only to ultimately reveal himself in all his glory.

“If it’s Matt Damon,” the professor continued, “he should look the same when he lands at Ithaca as when he finally is recognized, but even when he’s disguised as a beggar, the whole point is he’s gone from the highest in the social scale – which is the king – all the way to as low as you can go. In terms of traditional societies, he should be despised as an inferior human.”

“The big lesson is that he is – may I put it this way – beautiful on the inside, but ugly on the outside. And when he finally becomes the ‘real’ Odysseus, then he’s beautiful on the inside and outside, supposedly.” Despite this moment’s importance to the overall narrative, Nagy seemed to suggest, casting a universally acknowledged male lead like Matt Damon may make it difficult to pull off a believable beast-to-prince transformation.

Where Christopher Nolan’s Odyssey (Probably) Won’t Dare Be Accurate

“Is Matt Damon Going To Kill A Kid?”

There is one aspect of The Odyssey that Nagy believes even Christopher Nolan likely won’t touch: “And then, there [is] the problem of war crimes. How is the movie going to handle that?”

If you don’t remember Odysseus committing war crimes being a part of your experience learning about the Homeric epic, you’re not alone. But Nagy promised he “can prove to you that even The Odyssey is aware of a very, very questionable few moments in Odysseus’ life.” There is one “where he actually kills a child in war. How do you like that? And what are we going to do with it? Is Matt Damon going to kill a kid?”

“How the hell are you going to do that in a movie?”

Nagy explained that The Odyssey subtly nods to what could be Odysseus’ darkest moment during his time with a people called the Phaeacians. “He’s this total stranger who’s washed up onshore, but the royalty is suspecting he’s an important guy,” Nagy recounted, “so they don’t ask who he is; they just give him a very fancy dinner.” In return, Odysseus shares his story with his hosts.

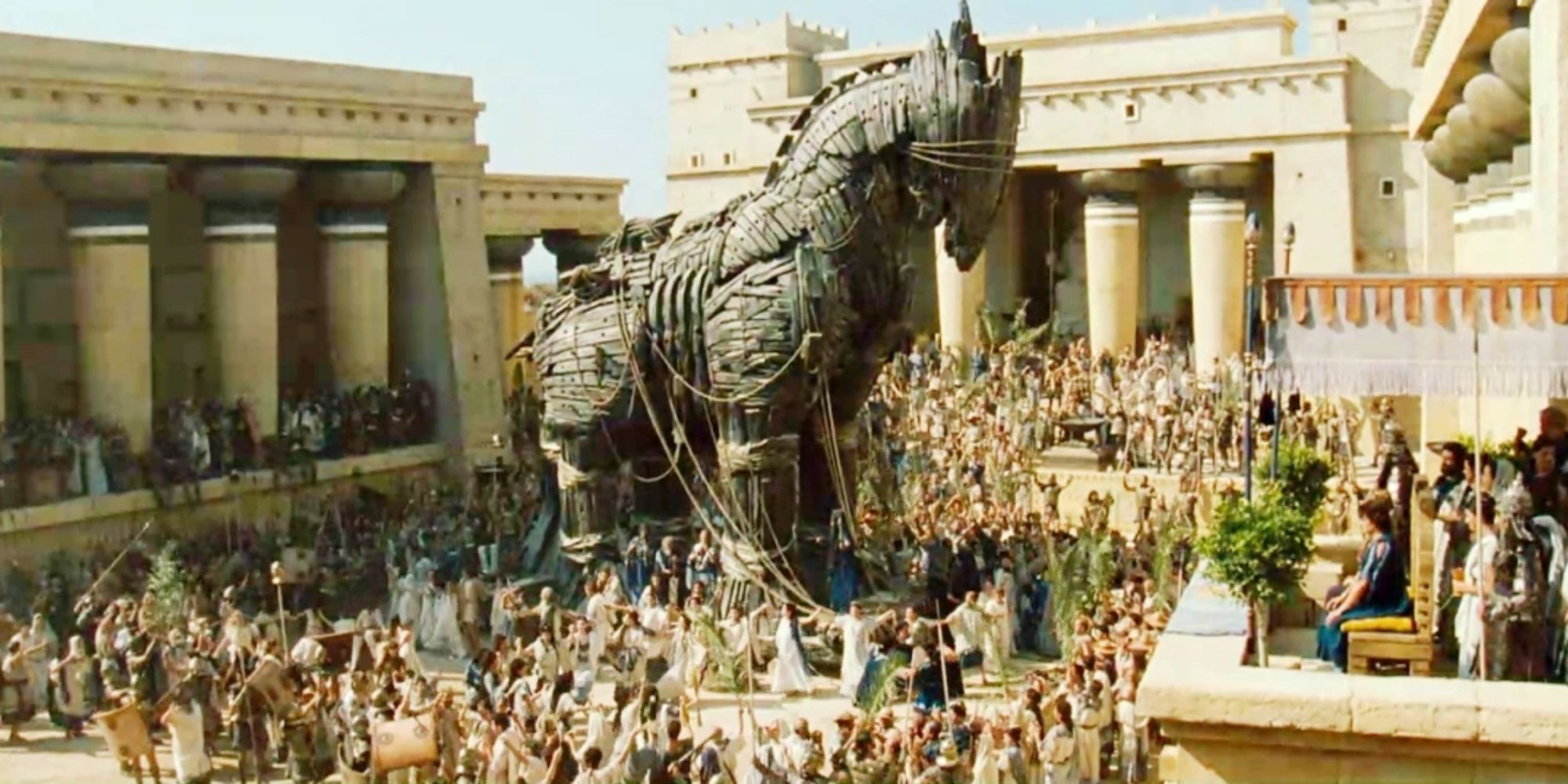

“He tells his story,” Nagy shared, “but he doesn’t really identify himself until a blind singer performs three songs … and [for] the last of the three songs, the disguised Odysseus says, ‘Could you sing the song of the tale of Troy?’ And, of course, he’s definitely a character in that, because he invented the Trojan Horse.”

“So, the story is told,” continued the professor, “[and] we have plot outlines of how that happened–that when Troy finally is captured, Odysseus himself takes the child of Hector and Andromache, who are the nicest people in The Iliad … to the highest point in Troy, and throws the baby to his death.”

Back with the Phaeacians, “when the blind singer gets to the part where the boy is captured … and Odysseus is going to go up and commit a war crime, the narrative stops and says, ‘While Odysseus was listening to this, he started crying. He was weeping and weeping and weeping, just like a captive woman when her child was killed.”

This speaks to one major distinction Nagy wants people to make when thinking about Odysseus: “I spent all my life telling young people, ‘Don’t use the word “hero” the way we use it when you think about ancient heroes.’ Ancient heroes, unlike the way we use the word, are not admirable in morality all the time. They’re just larger than life. So when they’re moral [say] 90% of the time, fine, then we really admire them. But there’s always at least a 10%–I’m making up the percentages–[where] they do morally questionable [or] horrific things.”

The Big Steps Troy (2004) Took Away From The Source Material

“Hardly A Reconstruction Of What Really Happened”

Christopher Nolan’s The Odyssey may not necessarily stick exactly to what would be historically – or Homerically – accurate, but it wouldn’t be the first adaptation of Homer’s epic poetry to take liberties. Nagy mentioned Wolfgang Petersen’s 2004 film Troy, which adapted The Iliad, as an example of a movie that didn’t quite accomplish its apparent ambition of accurately realizing the narrative. “[Petersen] followed the teachings of a very important archaeologist,” Nagy said, “but that guy had all sorts of theories that today’s archaeologists won’t accept anymore.”

“To me, that film was hardly a reconstruction of what really happened.”

That began with the actual design of Troy itself. The archaeologist in question “imagined that what he was excavating wasn’t just the citadel, but essentially the outlying area, and that the whole thing was almost like a modern city dominated by a citadel.” While that looked good on screen, Nagy said, “archaeologists today wouldn’t accept that.”

According to the professor, the director’s attempt to stick with what was “real” actually harmed Troy’s adherence to the epic poem. “This director, who’s a very smart person [and] very artistic, got so involved in the way this person reconstructed Troy as if the Homeric Iliad really were history, [and] naturally, one of the things that would happen is, ‘Well, then we can’t have gods … If The Iliad is history, let’s remove them.’”

Given Nagy’s belief that the works of Homer were meant to explain the workings of the cosmos, the removal of gods from Troy was actually a big step away from The Iliad. “I don’t care,” Nagy clarified, adding that “if it’s still gripping, fine.”

How Disney “Undermined” Hercules In Their Animated Classic

“Disney Studios Can’t Have An Illegitimate Child”

On the subject of adapting Greek mythology, Nagy also touched on Disney’s Hercules, the 1997 animated film that remains one of the studio’s classics. He revealed he’s seen the film many times, and that “there [are] some beautiful things in it.” But although “that one, I really admire,” he pointed out one major aspect of the movie that isn’t up to Greek mythological snuff. “What’s really ridiculous,” Nagy said, “is that Herc–as he’s called in the movie–is the son of Zeus, but he’s not the son of Hera. For God’s sake, that’s the whole point.”

“Heroes have to have mortality in their genes. You can’t just have two certified immortal gods have a kid, because then there would be a constant overthrowing of gods.”

“Hercules is the son of a mortal woman,” the professor continued, “which means that he has to die too … the dominant gene is us, so all it takes is one mortal in your family tree, and you’re mortal–even if you’re descended from Zeus. So, that’s already a big disappointment, because Disney Studios can’t have an illegitimate child.”

“[In Disney’s Hercules,] Zeus and Hera are the real mom and dad, which means that the heroic status of Hercules is undermined.”

That said, Nagy did praise one aspect of the movie. “There’s a retelling of a part of Meg’s life in silhouettes, in shadow theater,” he said, “and that’s almost a perfect retelling of [the classic] tragedy The Trojan Woman, which is really about another phase of Heracles’ life.” In Nagy’s eyes, “whoever did that 30-second retelling is a genius.”

“And there are a lot of things like that in Disney films,” he continued, “So, maybe the studio had to have Herc as a legitimate child of Zeus and Hera, which kind of messes up the whole mythological cosmos. There are other things that are very moving and very deep. And I love the way [the Muses] look like the Supremes in their prime. It’s brilliant. Just drop ᴅᴇᴀᴅ brilliant.”

Gregory Nagy’s Advice On Adapting The Odyssey

“The Trick Would Be Not To Be Too Little-Minded”

So, what would Nagy’s advice for Nolan, or anyone adapting The Odyssey ultimately be? He had a few points. First, he said, “I would take, especially dream sequences, [and] really have fun with how film can convey the meta-natural … I don’t like to say supernatural, but superhuman.”

Then, Nagy advocated for a complicated look at Odysseus and the narrative’s characters in general. “If somebody commits a war crime, then you say, ‘Oh, you’re not my hero anymore,’ that’s crazy, because that’s expecting a hundred percent perfection of humans, which is exactly what this medium is exploring. We’re sort of purging our emotional being.”

“Maybe the trick would be not to be too little-minded, and not to humor the ‘moral standards’ of today.”

The Odyssey is, after all, from a time in which ancient Greek gods and people alike were said to have committed acts that would be unthinkable today (Look up “Zeus the swan” as a quick, easy example). Nagy seemed to point toward the idea that such narratives were meant to offer a look at the complex and ever-shifting world around us, rather than prop up the sort of heroic paragon of virtue that might lead a summer tentpole film.

“If Odysseus is a complex character,” the professor said, “you can figure that the plot of the Odyssey is also complex.” Thankfully, Christopher Nolan is known for nuanced storytelling. And even if The Odyssey, for some reason, doesn’t turn out to be an example of that, you can bet that Gregory Nagy will still be in the audience. Or, in his words: “I love film, and so I will take anything.”

The Odyssey is set for release on July 17, 2026.