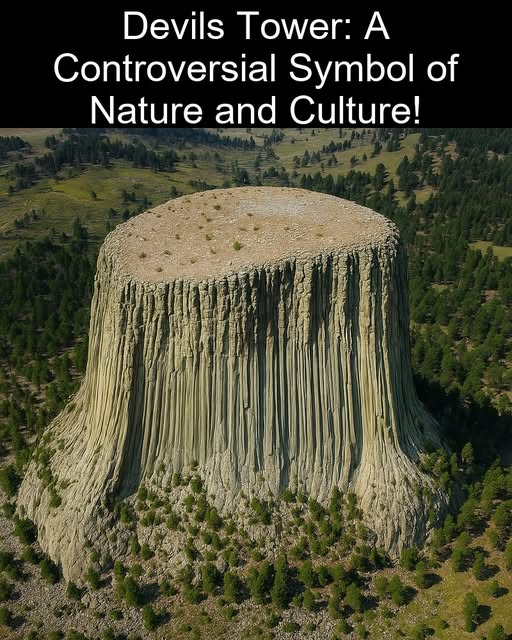

At dawn, the first light of day creeps across the high plains of Wyoming, washing the land in shades of amber and pearl. Out of this gentle glow, a shape begins to rise—a silhouette so improbable it seems conjured from a dream rather than carved by the patient hand of time. Devils Tower, immense and solitary, emerges from the rolling green like a colossal sentinel watching over the ages. Even from miles away, the monolith dominates the horizon, as though the earth itself has thrust a single, defiant finger into the sky.

Long before maps or monuments, before the names and borders that now divide the land, Devils Tower was already old. Fifty million years ago, deep beneath layers of ancient sediment, magma intruded into the crust, pressing upward through fractures and slowly cooling into hexagonal columns of phonolite porphyry. For countless millennia, softer rock around this core yielded to rain, wind, and frost, eroding grain by grain until only the hardened pillar remained. What stands today is a monument to both creation and destruction—a geological paradox that embodies the power of unseen forces shaping the visible world.

When the first peoples arrived here, they recognized the tower not only as a landmark but as a sacred place, alive with meaning and spirit. The Lakota called it Bear Lodge, a place where visions were sought and stories given form. Among the Kiowa, the tale of the seven sisters spoke of a giant bear pursuing children across the plains. In desperation, the girls prayed to the Great Spirit, who raised the ground beneath them. As the bear tried to climb, its mᴀssive claws scarred the rising walls, leaving behind the deep grooves that still mark the stone. The children were lifted to the stars, becoming the Pleiades—a reminder that even in the face of danger, the Earth itself can offer protection.

These legends were more than stories; they were ways of knowing, of binding people to land and to each other. For generations, ceremonies and prayers were held beneath the tower’s shadow. Cloth bundles carrying peтιтions and graтιтude fluttered from the branches of trees around the base. In these quiet acts, the tower became a relative, a living presence to be honored and respected.

In 1875, Colonel Richard Dodge led an expedition into the Black Hills and described the formation in a report. Misinterpretations of his translator rendered Bear Lodge as “Bad God’s Tower,” later simplified to Devils Tower—a name that, despite its origins in error, would become official. Within decades, explorers, geologists, and tourists were drawn by curiosity and wonder, eager to measure, climb, and pH๏τograph the monolith. Where once only quiet reverence had reigned, a new era of fascination began.

In 1893, ranchers William Rogers and Willard Ripley constructed a ladder bolted into a vertical fissure of the tower and climbed to the summit. Their feat, celebrated in newspapers, marked the beginning of recreational climbing here. Though their ascent was daring, it was also symbolic—a reflection of the era’s belief that any landscape could be tamed, any obstacle overcome by ingenuity. Yet to many Native people, this climb was a disruption, an intrusion on a place meant for prayer, not conquest.

When President Theodore Roosevelt declared Devils Tower the first national monument in 1906, he did so to preserve a wonder whose significance transcended any single culture. In the following decades, the site became a touchstone in debates over land use, cultural respect, and the meaning of public spaces. Modern climbers flocked to scale the tower’s dramatic cracks and columns, describing the ascent as both a physical challenge and a spiritual experience. Many pause each June during voluntary climbing closures, respecting Native ceremonies that still bring families to the base to pray and honor the ancestors.

Standing at the foot of the tower, you are struck by the improbable harmony of science and story. Geologists explain the fluted walls as the result of slow, predictable cooling. Yet when you run your hand along the stone, it feels alive, as if each groove remembers the claws of the giant bear or the hands that tied prayer cloths to nearby trees. The rational mind catalogues measurements—867 feet from base to summit, 1,267 acres in the monument—but the heart senses something beyond calculation: a deep, wordless knowing that this place is both ancient and immediate, both indifferent to and inseparable from human longing.

As the hours pᴀss, the tower transforms in the shifting light. In the noon sun, it gleams a pale gold; by twilight, its silhouette turns almost black against the darkening sky. Shadows gather between the columns like whispered secrets. Swallows dart in and out of hidden nests high on the cliffs, and the wind carries the scent of juniper and sage. On the summit, grᴀsses grow in cracks and small mammals make their burrows, proof that life always finds a foothold, even in stone.

The tower has become more than a landmark; it is a symbol in art, literature, and film. In Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Devils Tower was imagined as a cosmic meeting place, where humanity would come face to face with the unknown. That vision is not so different from the one held by the people who first told stories of the Pleiades—both perspectives understand the tower as a bridge between worlds.

For those who come here seeking adventure, Devils Tower offers a climb unlike any other. The vertical columns form natural routes that challenge even the most skilled climbers. Each ascent is an intimate negotiation with gravity and fear, requiring trust in the ancient rock and in one’s own determination. For others, simply to sit beneath the cliffs is enough—a chance to feel small in the best possible way, to be reminded that our lives are brief chapters in a much longer story.

As night falls, stars emerge above the tower, and the land settles into a deep, resonant quiet. In that hush, it is possible to sense the many layers of meaning that have gathered here: the geological forces that shaped the tower, the human hands that measured and climbed it, the voices that have prayed and sung to it across centuries. All these threads weave together into something enduring, something that defies any single interpretation.

Devils Tower endures because it holds space for contradiction. It is both sacred and scientific, familiar and alien, fixed in place and yet always changing in the shifting light. To stand before it is to feel that rare combination of awe and peace—to know that while we measure time in years and decades, this tower measures in eons.

Perhaps that is the gift it offers: the chance to see our own stories in the context of deep time, to glimpse the world as it was before us and as it will be long after. In its silent presence, we are reminded that we, too, are part of something ancient and unfinished—a story still unfolding beneath the endless sky.