A new study is rewriting the traditional explanation of the damaged statues of Queen Hatshepsut, one of only two female rulers of ancient Egypt. Long believed to have been victims of posthumous vengeance by her successor, Thutmose III, the statues are now thought to have been ritually and deliberately “deactivated,” not destroyed in anger.

Head of an Osiride statue of Hatshepsut, partially restored with plaster. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Head of an Osiride statue of Hatshepsut, partially restored with plaster. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Hatshepsut, often referred to as “The Woman Who Was King,” ruled during Egypt’s prosperous Eighteenth Dynasty. Her reign was one of flourishing trade, monumental constructions, and a relatively peaceful empire. However, when she died, the majority of her statues were found broken or removed, especially at her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, near Luxor. For nearly a century, scholars have ᴀssumed that such devastation was evidence of a damnatio memoriae—a deliberate attempt to erase her legacy.

But a new study by University of Toronto researcher Jun Yi Wong debunks that account. In a study published in the journal Antiquity, Wong examined thousands of pieces of statues uncovered during the 1922–1928 Metropolitan Museum of Art excavations. Drawing on previously unpublished field notes, pH๏τographs, drawings, and correspondence, he provides a more complex account of the damage to Hatshepsut’s statues.

“While the ‘shattered visage’ of Hatshepsut has come to dominate the popular perception, such an image does not reflect the treatment of her statuary in its entirety,” Wong wrote in his study. “Many of her statues survive in relatively good condition, with their faces virtually intact.”

Small kneeling statue of Hatshepsut with an intact face. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Small kneeling statue of Hatshepsut with an intact face. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Wong observed that the majority of statues were broken along structurally weak points—such as the neck, waist, and knees—a pattern also seen in a well-documented ancient Egyptian ritual known as “deactivation.” The purpose of the practice was to neutralize the spiritual power believed to reside within statues and was not specific to Hatshepsut, but also extended to male pharaohs and other elites. These breakages were not malicious acts but part of religious and funerary customs.

Further, the research indicates that most of the damage to Hatshepsut’s statues did not occur during the time of Thutmose III, but in later periods. Numerous fragments were used as building material or tools, some even during the Graeco-Roman era. These results indicate that pragmatic reuse at a later date significantly contributed to the statues’ condition.

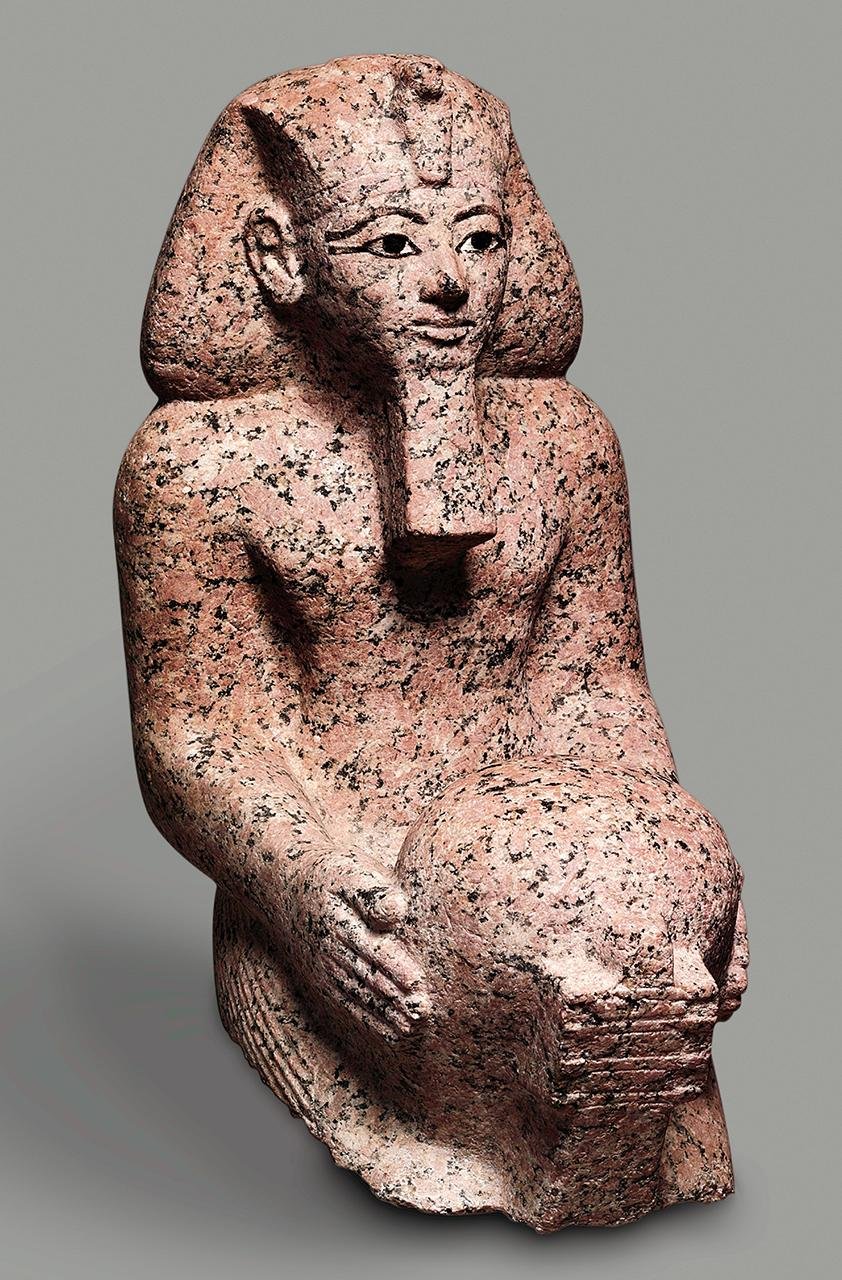

Seated statue of Hatshepsut. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Seated statue of Hatshepsut. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Wong conceded that Hatshepsut did face a campaign to suppress her memory. Her name was obliterated from some temple inscriptions and royal lists, and some of the iconographic symbols were altered. But the evidence from her statues tells a different story.

Far from being an isolated target of political rage, Hatshepsut appears to have been treated much like other deceased pharaohs. Her statues’ ritual deactivation may have served to affirm Thutmose III’s lineage and maintain dynastic legitimacy, rather than to erase her entirely.

More information: Wong, J. Y. (2025). The afterlife of Hatshepsut’s statuary. Antiquity, 99(405), 746–761. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.64