There is a street in Rome where time does not pᴀss—it lingers.

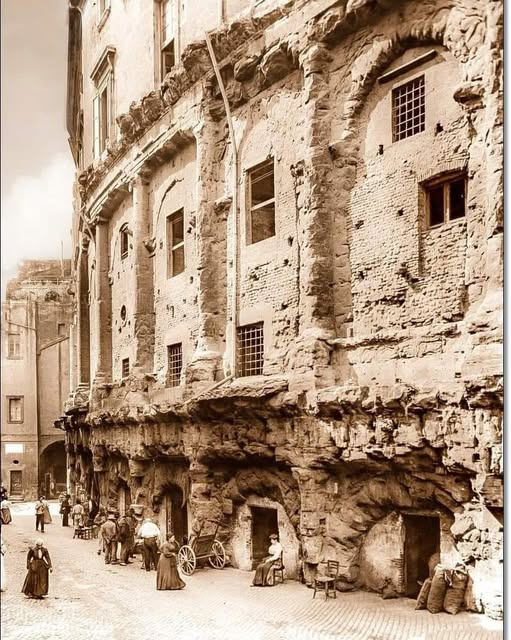

At first glance, the sepia image might seem like a corner of any old European town: people in heavy dresses, children barefoot on cobblestones, elderly men leaning on carts under morning sun. But behind them rises a wall unlike any other. Arched and ancient, it seems too grand for its current setting—like a lion quietly watching a marketplace. This is the Theatre of Marcellus, and this is its second life.

Commissioned by Julius Caesar but completed by Augustus in 13 BCE, the theatre was designed to awe. It was Rome’s largest at the time, capable of seating tens of thousands who gathered for plays, poetry, and public discourse. Built of tuff, concrete, and travertine, it represented the pinnacle of imperial engineering and artistic ambition.

But empires fall. And the applause fades.

By the 4th century CE, the Theatre of Marcellus fell into decline. Unlike many ruins that were swallowed by vines or buried in ash, this one remained visible—present, mᴀssive, and undeniably useful. As the Roman Empire crumbled and cities contracted, the people did what people always do with empty space: they moved in.

The theatre became a fortress in the Middle Ages. It pᴀssed through noble families—Frangipani, Savelli, Orsini—each of whom built palaces atop its stage and fitted rooms into its skeleton. In the Renaissance, the Orsini family transformed the upper tiers into a full residence, adding windows, staircases, and frescoed halls above the ghost of Caesar’s vision.

By the time this pH๏τograph was taken—likely in the late 19th century—the ground floor of the theatre had become a kind of urban cave. Lower-class families lived in its arches. The mᴀssive stones, once supporting triumphal scenes of tragedy and comedy, now bore the weight of beds, ovens, and daily Roman life. Horses drank water beside columns where senators once gathered. Children chased each other where actors had once died in pantomime.

What’s most powerful about this image is its quiet honesty. History is not clean. It does not always preserve itself in sterile perfection. More often, it is messy, repurposed, and lived-in. The theatre did not become a museum—it became a neighborhood. People built their lives in the bones of the empire.

This is not degradation. It is continuity.

As archaeologists began to restore parts of Rome in the 20th century, many such hybrids were removed in an effort to return structures to their “original” forms. But is there such a thing? The Theatre of Marcellus had lived several lifetimes—first as spectacle, then as fortress, then as home. It held stories that spanned millennia. Peeling away its outer skin would be like erasing chapters of a book to highlight only the first page.

And yet, Rome walks this tension constantly. Between ruin and rebirth. Between tourist spectacle and lived memory.

Today, the theatre’s lower levels are once again open to public admiration. The upper floors, still converted into apartments, are inhabited by modern Romans—those fortunate enough to call an ancient theatre home. From their windows, they overlook the Tiber and the echoes of empire. Their footsteps fall on stages where Virgil may have once been quoted, or where an emperor once smiled.

This image, then, is not merely a curiosity. It’s a reminder. Civilization does not always rise in perfect lines. Sometimes it folds back on itself. Sometimes it camps inside its own shadow. And sometimes, what we call “ruins” are just another form of shelter.

We often revere antiquity for its distance, for its mythic scale and grandeur. But what makes the Theatre of Marcellus remarkable is not its scale—it is its closeness. It let itself be used. It was not a relic, but a roof. And in doing so, it became immortal.

Perhaps all buildings dream of such a fate—not to be remembered in marble stillness, but to keep breathing through the laughter of children, the clatter of pots, the whispered stories told under their arches.

So next time you walk the ruins of an empire, pause. Listen not only for ancient footsteps, but for the distant sound of a cradle rocking. History, after all, is not only what we preserve. It’s what we live through.

<ʙuттon class="text-token-text-secondary hover:bg-token-bg-secondary rounded-lg" aria-label="Chia sẻ" aria-selected="false" data-state="closed">