If you could whisper across the ages, your voice would pᴀss through a thousand jaws before it reached the modern world. Along the way, it would change shape—not just in accent, tone, or language, but in the very way it is formed. The evolution of human speech is a tapestry woven with threads of culture, anatomy, and time. And curiously, one of the most pivotal threads is food.

On a quiet morning in a European excavation site, archaeologists gently brushed dirt from the face of a skull over 6,000 years old. Its teeth met neatly—edge to edge. A far cry from the modern bite we see in ourselves and those around us, where the upper teeth tend to rest slightly forward of the lower. That small distinction, once considered trivial, would soon become a key to understanding not just dental development, but the very evolution of sound itself.

A Chewier Past

Before agriculture, before cooking softened what nature provided, our ancestors chewed hard. Roots, nuts, raw meat, fibrous vegetables. Their jaws worked like hinges under pressure. It was demanding, repeтιтive, and sculpted the face—especially during childhood, when bones are still forming. A lifetime of gnawing built square jaws and broad arches, resulting in the now-unfamiliar “edge-to-edge” bite.

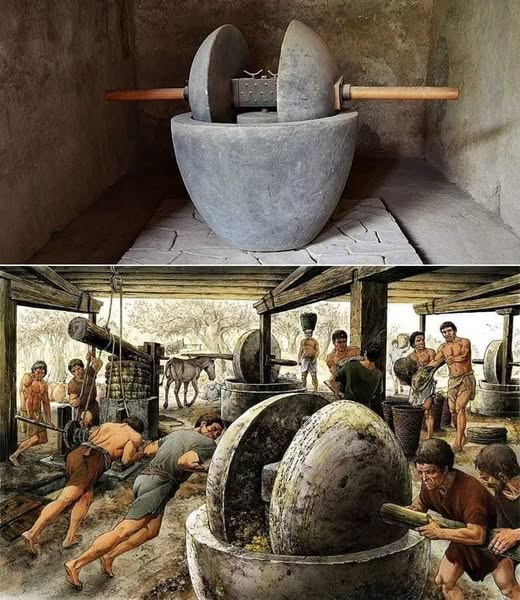

This bite was universal among hunter-gatherers and early humans. But it began to change around 10,000 years ago with the birth of agriculture and food preparation. In farming settlements scattered from the Fertile Crescent to Neolithic China, people began to process their food more thoroughly—grinding wheat into flour, boiling grains, cooking roots. By the Bronze Age, cheese had entered the diet, followed by stews and porridges. Food required less chewing.

What began as a dietary convenience had unexpected biological consequences.

The Rise of the Overbite

In 1985, linguist Charles Hockett proposed a radical idea: that changes in denтιтion might affect speech. At the time, the idea wasn’t widely accepted. But in 2019, a study led by Damián Blasi and colleagues offered striking evidence: modern overbites were a relatively recent development in human evolution, appearing mostly in agricultural societies. More importantly, these anatomical changes made certain sounds easier to produce—specifically, labiodental consonants like “f” and “v.”

Try it now: say “f.” Notice how your bottom lip touches your upper teeth? That motion is far easier when your teeth are slightly offset. In an edge-to-edge bite, such motion requires awkward effort. The data revealed that languages from societies with processed-food diets were far more likely to include these labiodental sounds. Where food softened, speech diversified.

This may explain why ancient Semitic languages, early Indo-European tongues, and even proto-Chinese dialects changed not only their vocabulary but their very phonetic architecture across millennia.

Bones That Speak

To hold an ancient skull in your hands is to listen to a language long silent. Not in words, but in structure. Jaws that never said “favor,” “victory,” or “love”—not because those feelings didn’t exist, but because the mechanics of making those sounds didn’t yet align.

The skulls in the image above tell that story without uttering a word. The one on the right—older, worn by time—bears the signature of hard labor: flat teeth, edge-to-edge alignment, a jaw sculpted by effort. The one on the left, likely from a later agricultural society, shows the modern overbite, a result of gentler eating, smoother chewing, and perhaps even the invention of cutlery.

These differences aren’t genetic. They’re environmental. Cultural. They reveal how our bodies, like our languages, are shaped by the world we create around us.

Softness That Changed Sound

There’s something wonderfully ironic about it: the move to softer food—something that might suggest weakness or laziness—actually gave rise to more nuanced, articulate speech. In a sense, civilization began to whisper where once it had to shout.

As cities grew and recipes multiplied, so did the range of human phonemes. Sound became a tool not just for survival but for poetry, persuasion, storytelling. From soft food came softer speech. From softer speech came more expressive language. And from that, the societies we know today.

We often think of evolution as something grand and sweeping—saber-toothed tigers, upright walking, the discovery of fire. But sometimes, evolution hides in the smallest gestures. A bite of bread. A sip of milk. A spoon fed to a child.

The Lingering Bite

Today, orthodontists work to “correct” our overbites, unaware they’re treating an echo of history. We chew gum. We eat pasta. We blend smoothies. Each of these modern acts removes one more layer of resistance from the jaw’s ancient workload.

But with that ease comes beauty—a fluidity in speech, an ability to say words that our ancestors could not form without effort. The sounds of “favor,” “vow,” and “forever” are born not just of thought and language, but of bone and bite.

And so we return to the present, holding a pH๏τograph like the one above—a split frame of then and now, fossil and future. Two faces. Two diets. Two ways of speaking.

What Remains

History doesn’t always leave scrolls and scripts. Sometimes it leaves enamel. A tooth is a time capsule. A jaw, a forgotten manuscript. In the silence of the grave, there are still voices—if you know how to listen.

So the next time you say something soft, something fleeting—like “love” or “life” or “forever”—remember the countless mouths that came before yours. The bones that couldn’t say it. The diets that reshaped the tongue. The choices that led to vowels and verbs and verses.

In the end, even the smallest things—like a shift to softer food—can change everything.

Even the sound of your voice.