It was the summer of 1920, in a quiet clearing near the edge of a pine forest in rural Wisconsin, that something fell from the sky. No thunder, no explosion—just a strange vibration in the earth that awoke farmers before dawn. Cattle bolted from pastures. Dogs howled. And in the early hours, as the mist began to lift, locals came upon a sight that would never appear in any official newspaper or archive.

A metallic object—round, smooth, and partially buried—lay smoldering in a crater of scorched earth. It was unlike any flying machine known at the time. No propellers. No wings. Just a disc, pockmarked with heat blisters and strange seams, roughly 25 feet in diameter. The surface bore circular markings that glinted faintly even under the dust.

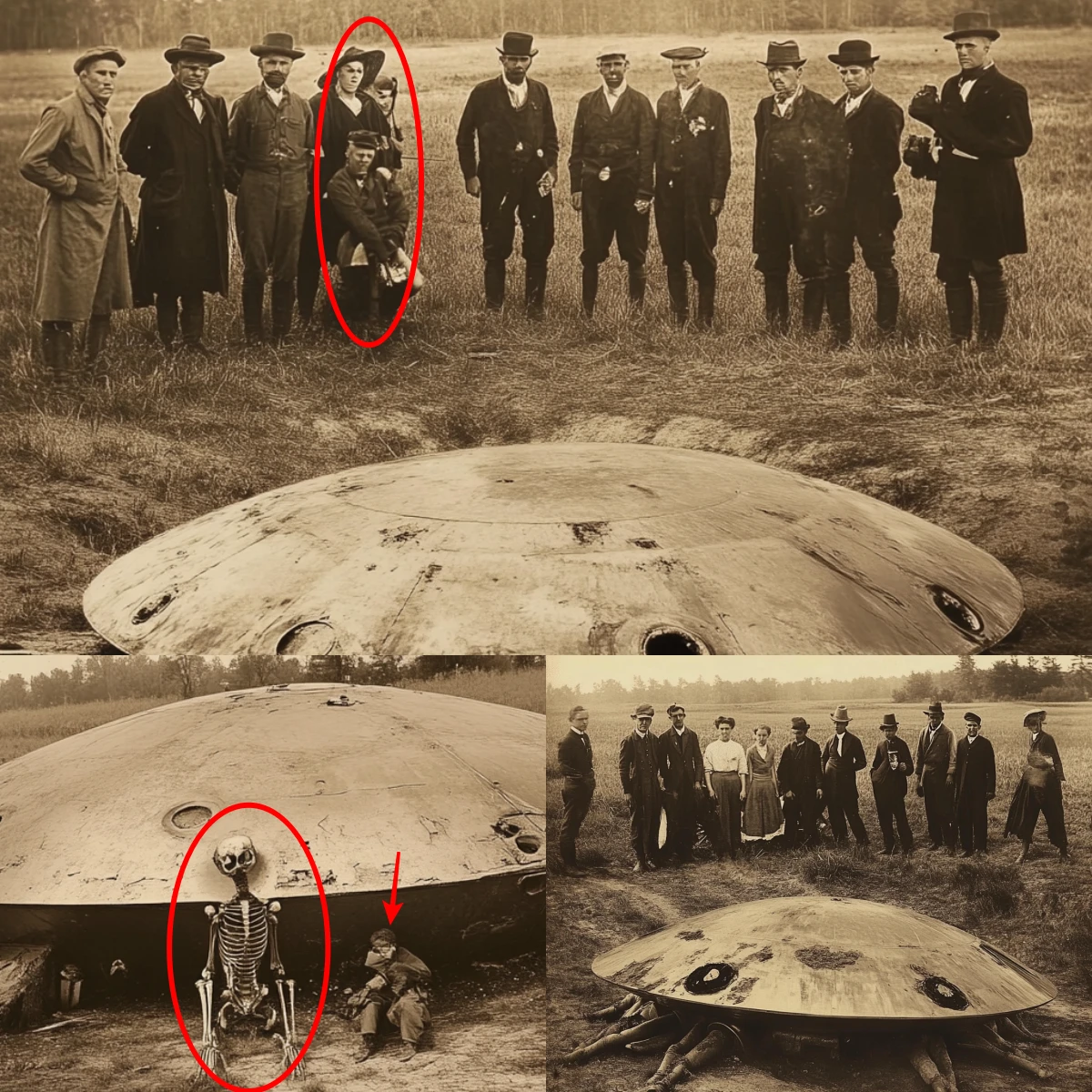

A group of locals gathered, their attire a mix of overalls and bowler hats, flannel and corsets. Some were farmers, others government men who had arrived mysteriously fast—too fast. A few of them carried notepads, one held a Geiger counter-like device far ahead of its time. And among them stood a woman in a wide-brimmed hat and military boots—her presence, calm and unreadable, would later disappear from all census records.

But what truly defied explanation was what lay beneath the craft.

One of the pH๏τographs—grainy, surreal—reveals a skeletal figure crouched under the disc’s rim. Humanoid in shape, but grotesquely out of proportion. The skull was elongated, the eye sockets mᴀssive and hollow. It had ribs, but too many; fingers, but not five. Some witnesses would later describe it as “like a child’s drawing of an angel, but stripped of all beauty.” The being was ᴅᴇᴀᴅ, though some accounts whispered it wasn’t when they found it.

Why no newspaper covered the event remains a mystery. One man, a local schoolteacher, wrote about it in his diary: “They came in black trucks by noon. Took our film. Took the thing. Took the hole it came in.” He was found a week later in a barn, alive but unable to speak. His journal vanished from the local library archive in 1954.

The operation was quick, surgical. The UFO was lifted by makeshift cranes before dusk, shrouded in canvas and hauled away. The field was leveled, topsoil trucked in. Trees were replanted to make the area look untouched. And all who saw it—farmers, housewives, even children—were sworn to silence, though whether by persuasion or threat remains uncertain. Some were paid. Others simply vanished. One of the men in the pH๏τo, a war veteran named Thomas Eberly, reportedly tried to publish a letter about the event in 1936. He was committed to a sanitarium two months later.

But not all records were destroyed. These pH๏τographs—four, fuzzy but unmistakable—surfaced in 1987 in a locked box at an estate auction in Connecticut. The seller claimed to be the granddaughter of a military pH๏τographer who had “seen too much.” Most dismissed them as hoaxes. But experts were puzzled: the images used a rare film type no longer produced by the mid-1930s. The degradation matched authentic materials of the time. No one could explain the level of detail or the consistent lighting and shadow. The craft, in every image, reflects its surroundings naturally.

Then there’s the question of the people.

Facial recognition software, applied decades later, identified two of the men in the pH๏τographs as low-level civil engineers working for the Army Air Service—neither of whom were known to have ever visited the Midwest. A third person, circled in one image and wearing a military-style hat, does not appear in any government record before 1920 or after. Some believe she was part of a shadowy predecessor to the later Majestic 12 group. Others suggest she wasn’t human at all.

But perhaps the most disturbing detail is found in the final pH๏τo: a wide sH๏τ of the craft resting in a shallow crater. Its underside appears slightly open—revealing spindly metal legs like those of an insect, retracted and blackened by heat. Around them lie marks in the earth, clawed impressions not consistent with landing gear. As if something had tried to escape—or crawl out.

What crashed in that field wasn’t just a machine. It was a threshold.

To some, it was an early test of reverse-engineered German technology, decades before the world would learn the name “Roswell.” But the simplicity of that explanation falters in the face of those bones. That elongated skull. That hollow stare frozen in the black-and-white stillness of a century past.

So why has this story remained buried?

The truth may be more psychological than political. In 1920, the world had just emerged from the First World War, bruised and bleeding. The influenza pandemic had ended. Humanity was looking forward—to industry, radio, flight, cinema. A story like this, had it broken public, would have fractured that fragile optimism. We weren’t ready for beings that came without warning, fell from the sky, and died silently in our fields.

But the silence itself shaped the world.

Because if this event truly happened—and more than a few researchers believe it did—then everything that came after was merely a continuation of the cover-up. Roswell wasn’t the beginning, but the second act. The true first contact had already happened in a Wisconsin field, 27 years earlier. And it wasn’t a greeting. It was a crash.

No lights in the sky. No greeting from the stars. Just a fall. A fracture. A mystery too heavy to be carried by history.

And now, more than a century later, these pH๏τos resurface in digital threads, grainy and quiet, speaking in visual whispers. We stare at them the way we stare at ghost stories—half skeptical, half afraid they might be true.

Because if they are… what else has been buried?

And what if, one day, something else falls—and this time, it’s not alone?

<ʙuттon class="text-token-text-secondary hover:bg-token-bg-secondary rounded-lg" aria-label="Chia sẻ" aria-selected="false" data-state="closed">