People used to think for a long time that family life in ancient Egypt was just very similar to a modern Western family: parents, children, and grandchildren living independently and forming new households. But recent research paints a more complex picture.

A group of men standing next to each other on a wall. Pixabay

A group of men standing next to each other on a wall. Pixabay

Steffie van Gompel, a Ph.D. candidate in Egyptology, has been researching ancient Egyptian marriage contracts for years. They reveal to us far more than the financial agreements between the two partners, shedding light on how Egyptian families were structured and presenting a different picture of the status of women in that society.

It is true that ancient Egyptian women did enjoy rights that differentiated them from women in nations like ancient Greece. They could own property, and their marriages came with contracts outlining financial arrangements. Popular culture has tended to use these observations to portray ancient Egyptian women as early feminists, independent and progressive.

But van Gompel insists this is a misleading simplification. Ownership of property is just part of the story about a woman’s place. You need to look at the family system, and more specifically, inheritance patterns and household organization.

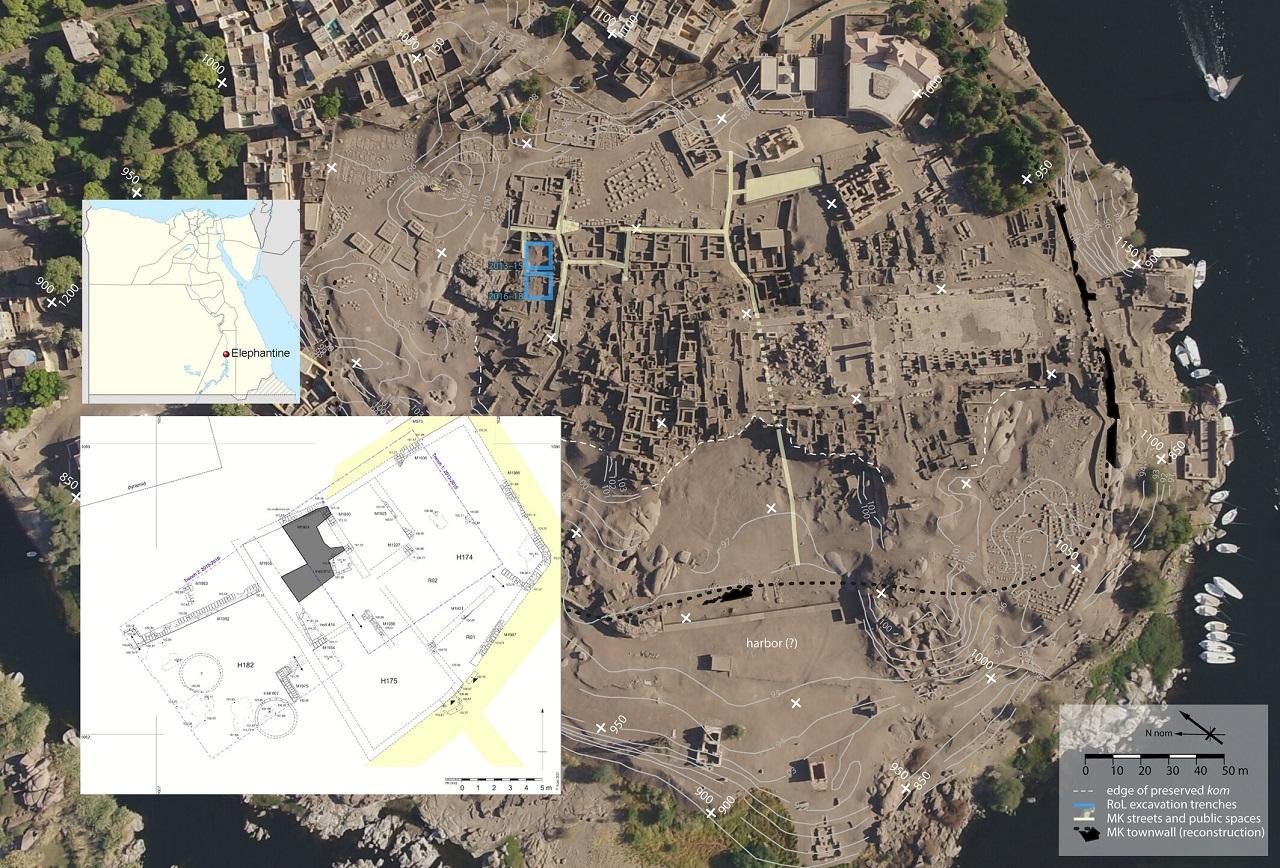

Women at a Banquet, by Nina de Garis Davies (1881–1965); original New Kingdom (ca. 1400–1390 BCE). Metropolitan Museum of Art

Women at a Banquet, by Nina de Garis Davies (1881–1965); original New Kingdom (ca. 1400–1390 BCE). Metropolitan Museum of Art

Her research combined classic Egyptology—the translation of ancient texts—with the tools of historical demography. By comparing Egyptian family models with non-Egyptian types from other cultures and historical periods, she uncovered something surprising: the Egyptians likely had a clan-based family structure, rather than the nuclear model we usually imagine.

In this system, the majority of children eventually moved out, but one usually stayed behind. Ideally, it was the eldest son. He would continue the family household, often with his wife, living with his parents. Therefore, many Egyptian households included at least three generations together, at least on a temporary basis.

This concentrated power in the hands of older male family members. Fathers, and later eldest sons, tended to control not only property but also the decisions about who their children could marry. Family property remained in the hands of these male household heads, even after marriage.

It’s not difficult to see why van Gompel describes ancient Egypt as “quite literally a patriarchy.”

But this system also created internal compeтιтion—not necessarily between women, but among siblings. The firstborn son was often set against the rest of the family. Quirky as it seems, this compeтιтion had the effect of protecting daughters from being sidelined purely because of being female. Where there was no eldest son, daughters could be chosen to carry on the family legacy, sometimes even in preference to nephews.

Thus, while women in ancient Egypt were not entirely without agency, their situation was shaped more by family politics than by any form of early feminism. They could inherit property, sometimes control households, and sometimes play central family roles. But they remained within an extremely patriarchal framework.

The image of ancient Egyptian women as feminist icons doesn’t fully hold up under this new scrutiny. As van Gompel admits, “I’m afraid I’ve overturned that cherished notion.”

More information: Leiden University