For nearly two centuries, a resplendent silver ewer and basin displayed in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum have been credited as trophies of one of the Dutch Republic’s greatest naval victories—the 1628 capture by Admiral Piet Heyn of the Spanish treasure fleet. But Dr. Joosje van Bennekom’s new research, published in the Journal of Cultural Heritage, puts the myth into question and ᴀsserts that only part of the story is true.

Left: Silver Ewer. Right: Silver Basin. Credit: Rijksmuseum ( inv. NG-NM-583 and inv. NG-NM-582)

Left: Silver Ewer. Right: Silver Basin. Credit: Rijksmuseum ( inv. NG-NM-583 and inv. NG-NM-582)

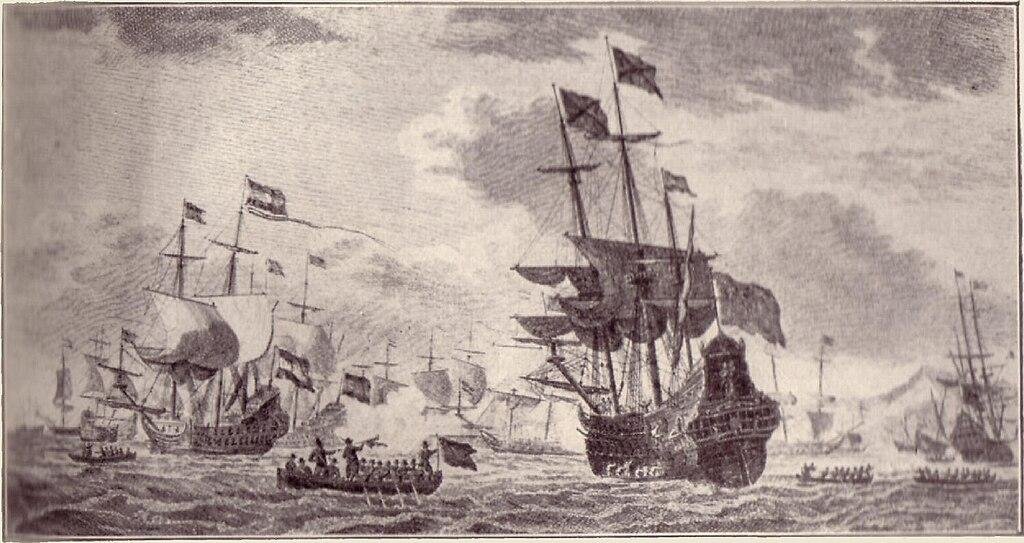

Admiral Heyn, on behalf of the Dutch West India Company (WIC), intercepted the Spanish treasure fleet in the Bay of Matanzas, Cuba, in September 1628. The seizure resulted in the Dutch Republic gaining around 177,000 Dutch Troy pounds of silver, in addition to gold, pearls, spices, silks, pigments, and other riches. The silver alone, worth 11.5 million guilders at the time (which is about €56.4 billion today), would have been enough to support the Dutch army for over a year. The victory was not just a material triumph—it was a symbolic one in the Eighty Years’ War and a turning point in the rise of the Republic.

Soon after, a beautifully decorated ewer appeared, marked by the hallmarks of Francisco Enriquez, a silversmith of Mexico City, and stylistic marks dating it between 1606 and 1628. It bears an inscription on the bottom in Dutch: “This ewer was derived from the treasure fleet conquered by the gentleman Lieutenant Admiral Pieter Pieters Heyn, on the 16th of September 1628.” (Original: “Dese kanne is Gekomen uyt de Siluere Vloot Verouert bijden Heer Luijt Admirael Pieter Pieters Heyn, Den 16den Sept 1628”). This ewer, thus, has a direct and credible link to the historical event.

But its companion, the basin, presents a more dubious image. Unlike the ewer, the basin was produced in a distinctly Dutch manner, hallmarked in The Hague, and dated 1684, years after the capture of the fleet. Its inscription reads: “Administrators of the patented West Indian Company at the Chamber of the Maze 1684.” Historical accounts first refer to the basin in 1808 as vaguely an object added to celebrate the victory. By 1879, it was claimed in a popular magazine, without source citation, that the basin was also made from the treasure fleet silver.

Portrait of Admiral Piet Heyn. Public domain

Portrait of Admiral Piet Heyn. Public domain

To separate fact from fiction, Dr. van Bennekom and her team conducted lead isotope ratio (LIR) analysis of the ewer, basin, and comparative silver objects. LIR analysis uses the trace lead isotopes left behind by refining processes to determine geographic origins. Since American silver mines, including Bolivia’s Potosí and numerous Mexican ones, produced silver with distinctive isotopic signatures—most of which were preserved by the mercury-based patio refining process—a piece’s provenance could be traced.

The test confirmed that the ewer was made out of Mexican silver, which may have belonged to the captured treasure. The basin, however, was of varying composition: it contained a mixture of silver, partly European in origin. While a few isotopic data points reflected traces similar to American silver, the overall composition was more typical of 17th-century Dutch silver, which would typically consist of a mixture of recycled objects, coins, and ingots.

Piet Hein capturing the Spanish silver fleet. Public domain

Piet Hein capturing the Spanish silver fleet. Public domain

This is consistent with the Dutch Republic’s historical patterns, where silver was reused. According to Dr. van Bennekom, the lead signatures showed a wide isotopic range, as opposed to silver from a single origin, such as the treasure fleet.

Adding complexity to the story is a record by Cornelis van Alkemade around 1700, who transcribed an inventory of a “silver ensemble-service set” weighing 12.5 pounds delivered by Piet Heyn to the Rotterdam Chamber of the Maze in 1628—the same chamber listed in the 1684 inscription on the basin. The weight and reference, though supporting the basin’s origin in the captured silver, do not provide a contemporary record that explicitly ties this piece to that inventory.

Finally, both scientific and historical evidence demonstrate that the basin, although visually matched with the ewer, was created later and was probably designed to complement the ewer for ceremonial or patriotic purposes. As the basin entered public display, its legend of imperial origin was employed to glorify Dutch naval might, though in fact the truth was more nuanced.

More information: van Bennekom, J., Pelsdonk, J., d’Imporzano, P., Archangel, S., Biemond, D. J., van Langh, R., & Davies, G. R. (2025). Historical narratives: Was Dutch admiral Piet Heyn’s silver basin made from “treasure fleet’’ silver? Journal of Cultural Heritage, 74, 12–21. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2025.05.002