Archaeologists have uncovered more than 100 prehistoric speleofacts—stalagmites that had been intentionally broken, moved, or reᴀssembled by humans—inside Cova Dones, a cave in Millares, Valencia. The discovery places the site among the most significant in Europe for prehistoric use of underground areas, second only to the Saint-Marcel cave in France.

Researcher Aitor Ruiz-Redondo (Unizar) illuminating one of the speleofact sets. Credit: University of Alicante

Researcher Aitor Ruiz-Redondo (Unizar) illuminating one of the speleofact sets. Credit: University of Alicante

The research is being led by archaeologists from the University of Alicante (UA) and the University of Zaragoza (Unizar), under the DONARQ project. The team is made up of a multidisciplinary group of specialists from insтιтutions across Spain and France, among them is postdoctoral researcher Iñaki Intxaurbe Alberdi from the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) and the University of Bordeaux, whose expertise in cave formation and human uses of karst landscapes has been vital.

Alberdi confirmed at least 100 of these formations in different sections of the cave. That many of the fractures also show calcite regrowth is strong evidence that the modifications occurred in prehistoric times, even though precise dating is still ongoing.

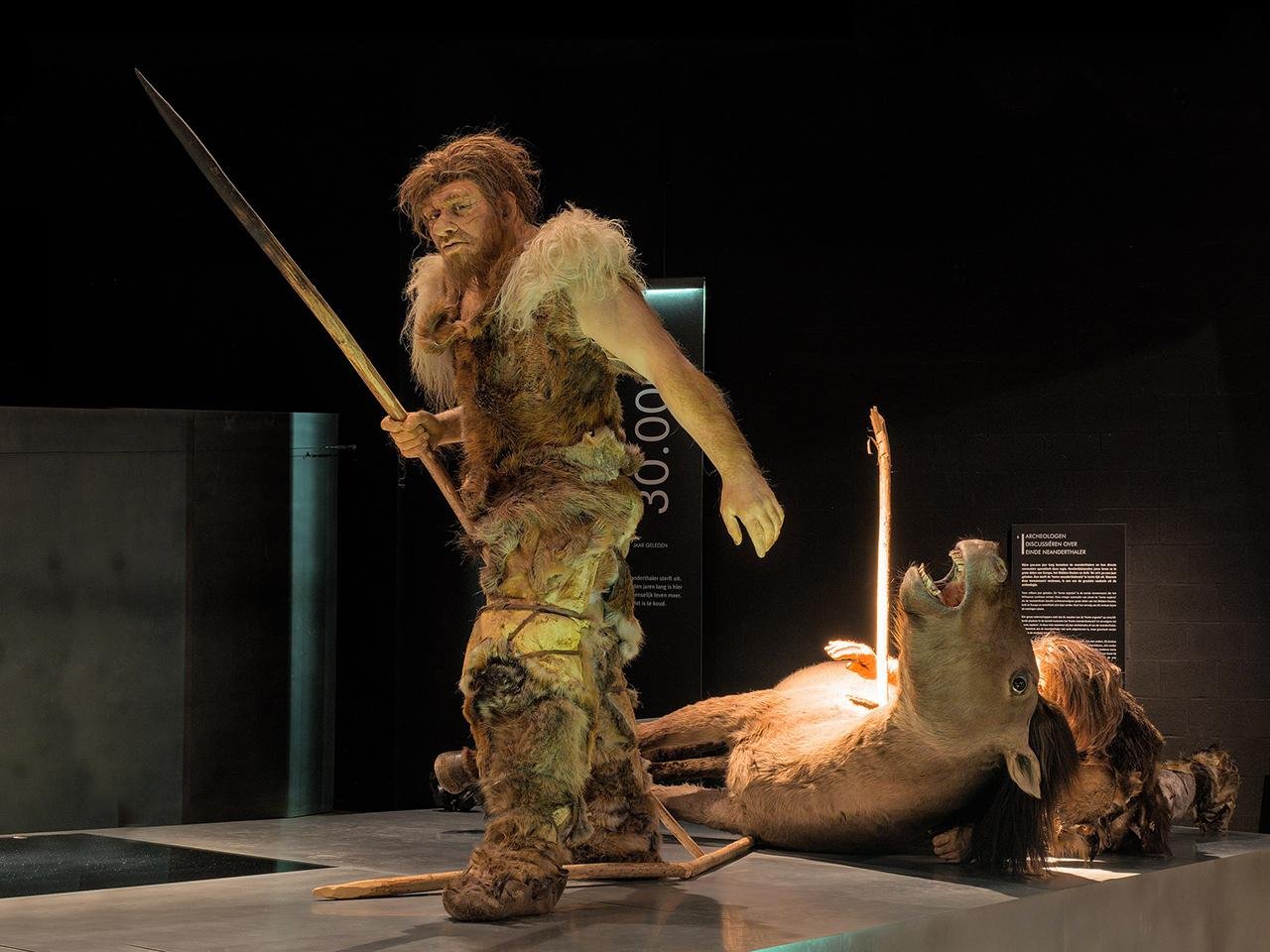

The speleofacts, which were created by the breakage and repositioning of stalagmites into deliberate patterns, have raised intriguing questions about their function. Some have suggested that they might have had ritual or symbolic use, perhaps being connected to early spirituality or social practice, while others have suggested more practical functions, such as barriers or markers to facilitate movement through the cave. A similar discovery in France’s Bruniquel Cave, dating back some 175,000 years and attributed to Neanderthals, has demonstrated the cognitive ability required for such activities.

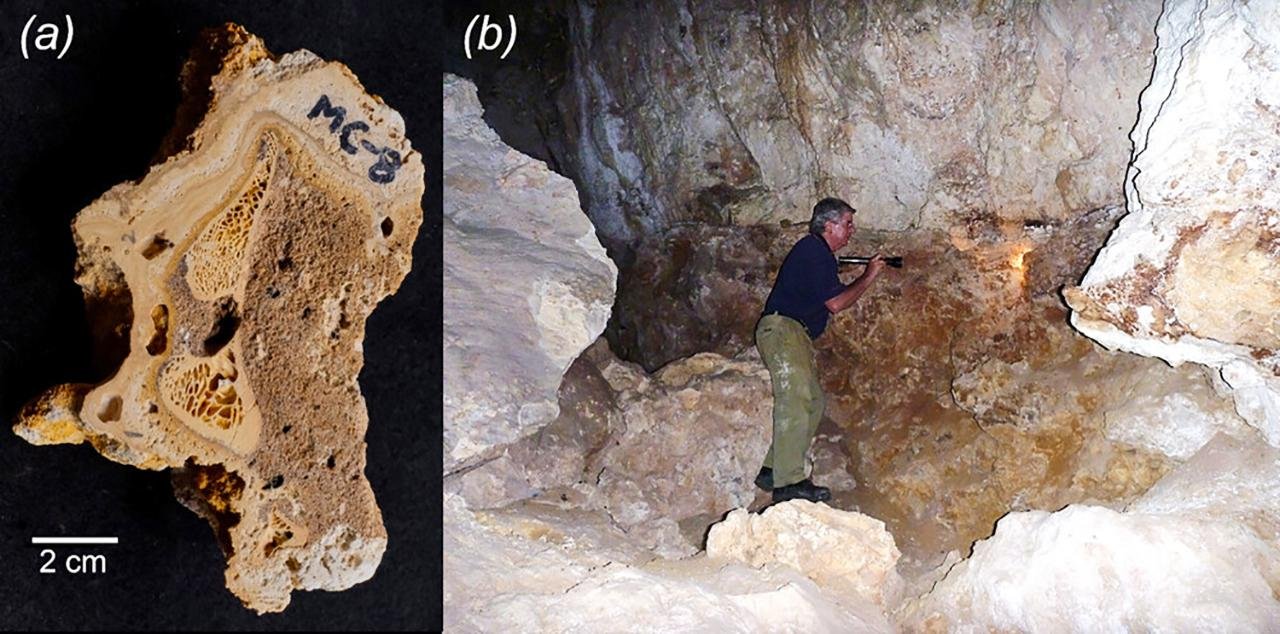

A large stalagmite sectioned and redeposited to facilitate transit through the cave interior. Credit: University of Alicante

A large stalagmite sectioned and redeposited to facilitate transit through the cave interior. Credit: University of Alicante

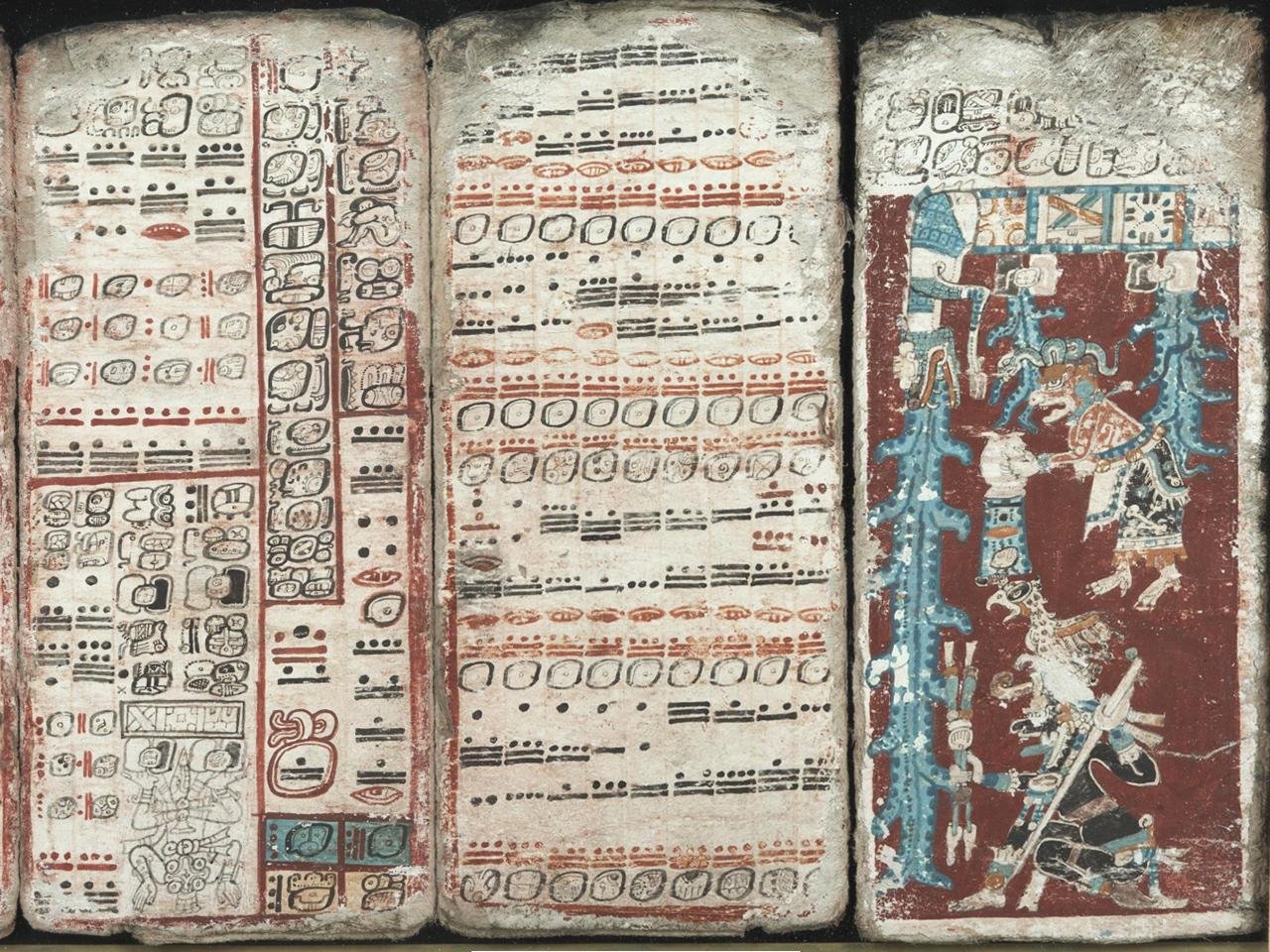

Cova Dones is no stranger to archaeological significance. In 2023, the academic journal Antiquity reported that the cave holds the largest known collection of Paleolithic rock art on the eastern Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula, comprising over 100 engravings and paintings that have been dated to approximately 24,000 years ago. The drawings are of a number of animals, including horses, aurochs, hinds, and stags.

After the rock art was discovered, archaeologists unearthed a Roman sanctuary deep within the cave. It contained Latin inscriptions and a coin from the time of Emperor Claudius, adding another layer of historic depth to the site.

Researcher Virginia Barciela (UA) next to a structure found in Cova Dones cave. Credit: University of Alicante

Researcher Virginia Barciela (UA) next to a structure found in Cova Dones cave. Credit: University of Alicante

Researchers now believe that Cova Dones had a complex and multifaceted role in prehistory. Rather than simply a shelter or a pᴀssageway, the cave was symbolically or ceremonially important to those who visited and modified it over thousands of years.

More information: University of Alicante