In a recent discovery revealing one of humanity’s earliest known episodes of conflict, researchers have uncovered evidence that a young man buried nearly 17,000 years ago in what is now northern Italy was killed in a violent ambush. The find, which was published in the journal Scientific Reports, indicates that the man, who has been named Tagliente 1, was killed by fatal wounds from flint-tipped projectiles, one of the first known victims of intergroup violence among prehistoric hunter-gatherers.

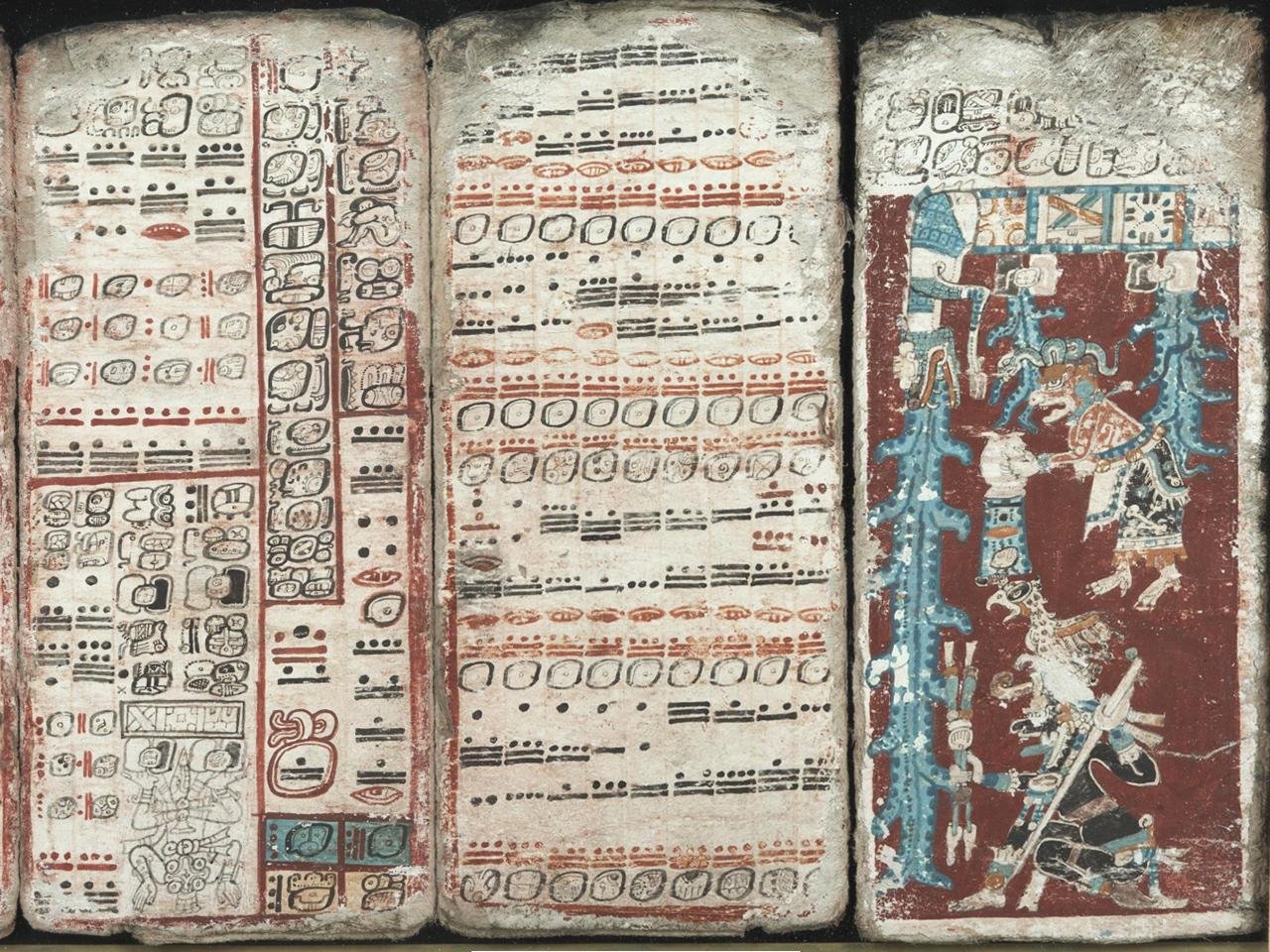

Illustration depicting intergroup violence and conflict during the Stone Age. Shanxi Provincial Museum, Taiyuan. Credit: Gary Todd/Public domain

Illustration depicting intergroup violence and conflict during the Stone Age. Shanxi Provincial Museum, Taiyuan. Credit: Gary Todd/Public domain

Tagliente 1’s skeleton was first excavated in 1973 at the Riparo Tagliente rock shelter in the Lessini Mountains of northeastern Italy. His lower limbs and some fragments of his upper body were found then because the burial ground had already been disturbed. The man, who is thought to have been between 22 and 30 years old when he died, lived during the Late Epigravettian period, after the Last Glacial Maximum—the coldest point of the last Ice Age.

For decades, the cause of his death was a mystery. But a new reanalysis employing advanced 3D imaging and scanning electron microscopy has changed that. University of Cagliari bioarchaeologist Vitale Sparacello, a co-author of the study, examined deep incisions on the left femur and tibia of the skeleton. In the past, they had been seen as post-mortem damage or ritual defleshing. But with the application of new imaging techniques, they were instead identified as projectile impact marks (PIMs) caused by high-speed flint-tipped projectiles.

The study revealed five discrete cut marks—four of which were found to be consistent with wounds inflicted by thrown flint-tipped projectiles. One wound on the front of the thigh and another wound on the back of the lower leg are interpreted as Tagliente 1 possibly running away, being attacked, or surrounded by more than one ᴀssailant.

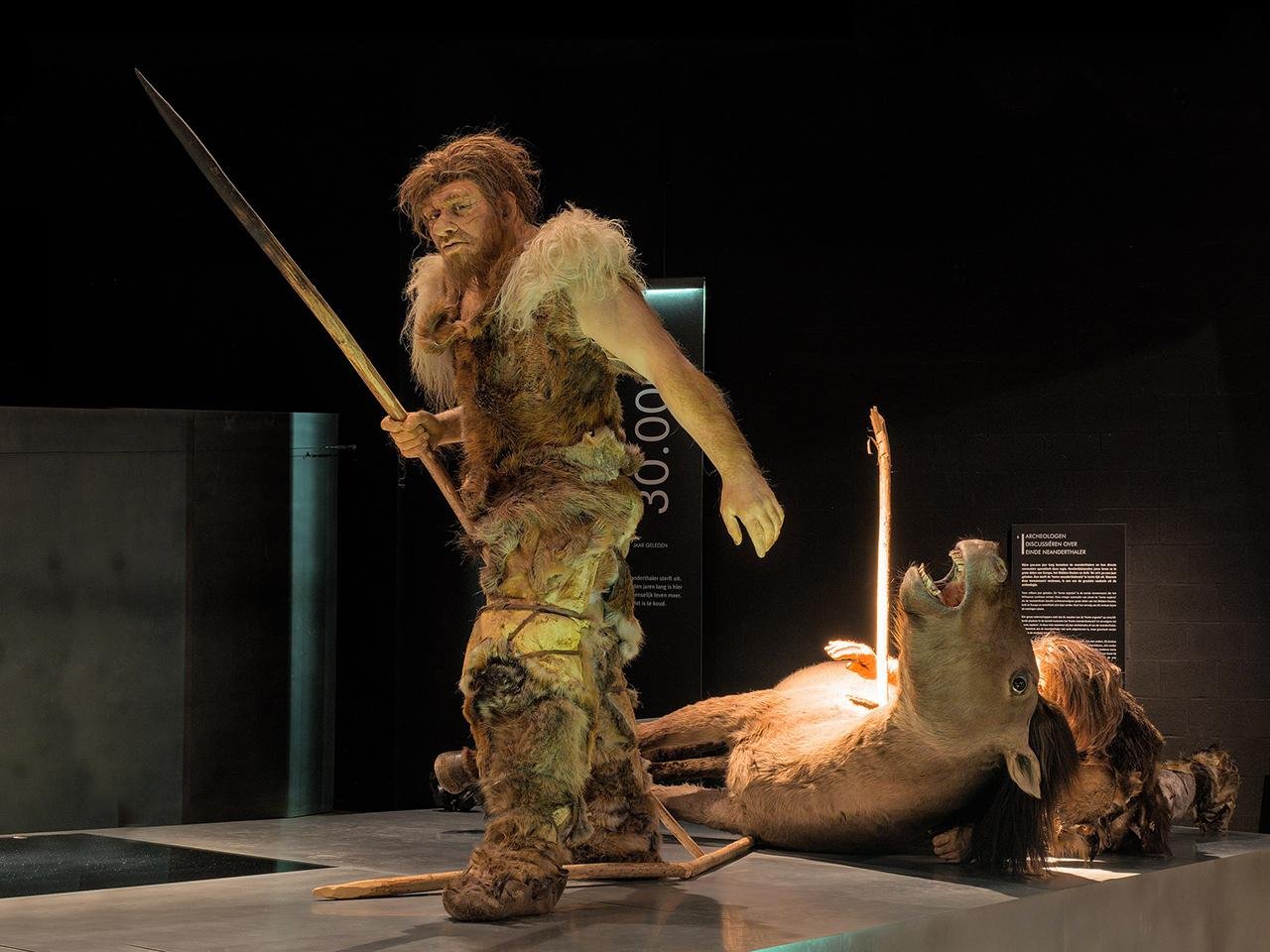

Three projectile impact marks found on Tagliente 1’s left femur. Credit: Sparacello VS et al., Scientific Reports (2025) – This image is used under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND license for non-commercial, educational, and informational purposes. If you are the copyright holder and have any concerns regarding its use, please contact us for prompt removal.

Three projectile impact marks found on Tagliente 1’s left femur. Credit: Sparacello VS et al., Scientific Reports (2025) – This image is used under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND license for non-commercial, educational, and informational purposes. If you are the copyright holder and have any concerns regarding its use, please contact us for prompt removal.

Unlike other exceptional Paleolithic cases where stone arrowheads are lodged in bone, this is the first time such an incident has been identified solely based on skeletal trauma analysis. Microscopic scrapes and the steep, abrupt inclines of the cuts all suggest that the wounds would not have been caused by cutting tools or by animal injury, but by weapons adapted for use in deliberate high-speed attacks.

Archaeologists ᴀssume that this violence most likely stemmed from compeтιтion over resources and territory. When glaciers melted and new lands became accessible in the Alps, human groups would have increasingly come into contact with one another, with occasionally ᴅᴇᴀᴅly consequences. Ethnographic studies show that in small-scale mobile groups, projectile weapons were generally used not for personal disputes but for ambushes or raids—strategic acts of intergroup aggression.

The burial itself is another layer of the story. His death was perhaps violent, but Tagliente 1 was laid to rest with dignity and ceremony. He was laid out on his back in a shallow pit, his arms extended. Large stones covered his legs—one of which had carvings of a lion and the horn of an aurochs—and pebbles stained with ochre and a pierced shell were placed nearby, perhaps as grave offerings or ritual symbols.

This contrast between violence and reverence is intriguing. Was Tagliente 1 honored for being brave? Was he buried as a communal act to cope with the trauma of his death? It is the view of some scholars that such burials could have been a way of ritually addressing the social disruption that violent and untimely deaths would have caused.

Though we’ll likely never know for sure who attacked Tagliente 1 or why, his bones offer us a unique and valuable glimpse into the shadowy side of Paleolithic life.

More information: Sparacello, V.S., Thun Hohenstein, U., Boschin, F. et al. (2025). Projectile weapon injuries in the Riparo Tagliente burial (Veneto, Italy) provide early evidence of Late Upper Paleolithic intergroup conflict. Sci Rep 15, 14857. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-94095-x