A new archaeological report by Bournemouth University (BU) is redrafting one of the most important pages of British history. Long believed to be the location of a bloody mᴀssacre during the Roman conquest of Britain, the “war cemetery” at Maiden Castle in Dorset now appears to have a more complex—and less Roman-centered—story to tell.

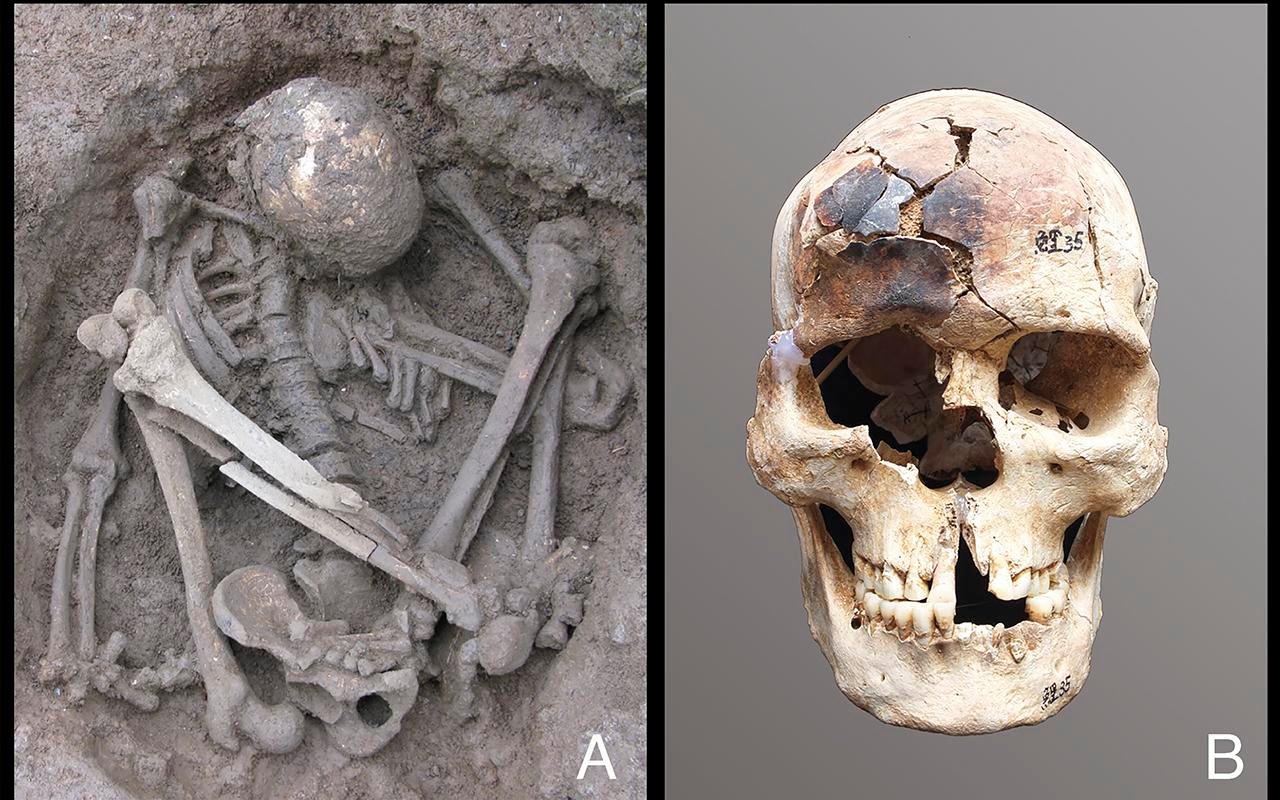

Two of the skeletons excavated by Mortimer Wheeler in the 1930s, dating from the 1st century AD. Both these individuals exhibit bladed weapon injuries, whilst one has a spear head lodged in his spine, previously interpreted (wrongly) as a Roman ballista bolt. Credit: Martin Smith

Two of the skeletons excavated by Mortimer Wheeler in the 1930s, dating from the 1st century AD. Both these individuals exhibit bladed weapon injuries, whilst one has a spear head lodged in his spine, previously interpreted (wrongly) as a Roman ballista bolt. Credit: Martin Smith

In a study published in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology, BU researchers conducted a new re-analysis of the Maiden Castle burials, complete with new radiocarbon dates. In contrast to the long-held presumption that the dozens of bodies discovered at the site were victims of a single, catastrophic Roman attack, current evidence suggests that these individuals died over a period of decades, between the late first century BCE and the early first century CE. The research suggests episodic outbreaks of violence, possibly due to internal conflict, dynastic power struggles, or regional executions, as opposed to a single battle against Roman forces.

Dr. Martin Smith, a BU ᴀssociate Professor of Forensic and Biological Anthropology, emphasized the significance of this find. “The discovery of dozens of human skeletons displaying lethal weapon injuries was never in doubt,” explained Smith. “However, by undertaking a systematic programme of radiocarbon dating, we have been able to establish that these individuals died over a period of decades, rather than in a single terrible event.”

Maiden Castle, an Iron Age hillfort, gained attention in 1936 when archaeologist Sir Mortimer Wheeler excavated it. Wheeler declared at the time that the hillfort had fallen to a Roman legion, displaying the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ as the last defenders of native Britain. His sensational story, set against the background of an approaching World War, took hold in popular culture and was widely accepted in academic and popular imagination.

Aerial view of Maiden Castle, Dorset, the largest Iron Age hillfort in Britain. Credit: Jo and Sue Crane

Aerial view of Maiden Castle, Dorset, the largest Iron Age hillfort in Britain. Credit: Jo and Sue Crane

But BU’s Principal Academic in Prehistoric and Roman Archaeology and excavation director, Dr. Miles Russell, now believes that this account is more myth than fact. “Since the 1930s, the story of Britons fighting Romans at one of the largest hillforts in the country has become a fixture in historical literature,” Russell said. “The tale of innocent men and women of the local Durotriges tribe being slaughtered by Rome is powerful and poignant… but the archaeological evidence now points to it being untrue. This was a case of Britons killing Britons, the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ being buried in a long-abandoned fortification. The Roman army committed many atrocities, but this does not appear to be one of them.”

The new evidence also raises broader questions about how ancient burial grounds across Britain can be interpreted. The variety of burial practices uncovered at Maiden Castle suggests either the presence of multiple distinct cultural groups or intricate social hierarchies that dictated burial customs, according to BU Visiting Fellow Paul Cheetham. “While Wheeler’s excavation was excellent, he was only able to investigate a fraction of the site,” said Cheetham. “It is likely that a larger number of burials remain undiscovered around the immense ramparts.”

Cheetham also added that the study defies simplistic explanations of archaeological cemeteries. “The intermingling of differing cultural burial practices contemporaneously shows that simplistic approaches to interpreting archaeological cemeteries must now be questioned,” he stated.

More information: Bournemouth University

More information: Smith, M., Russell, M., & Cheetham, P. (2025). Fraught with high tragedy: A contextual and chronological reconsideration of the Maiden Castle iron age ‘war cemetery’ (England). Oxford Journal of Archaeology. doi:10.1111/ojoa.12324