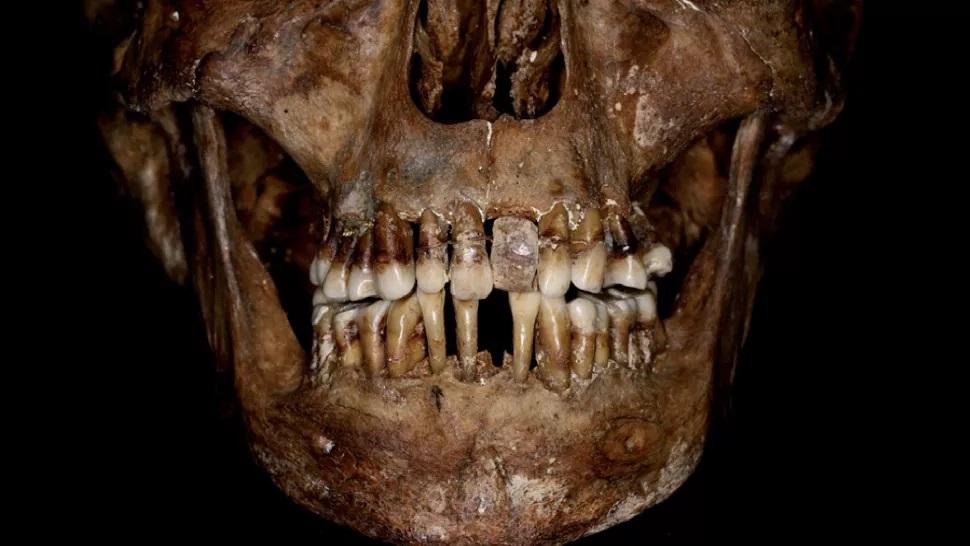

A recent study has revealed that an aristocratic French woman from the turn of the 17th century used fine gold wires to secure her teeth, a practice that may have worsened her dental condition. The woman was suffering an inflammation of the gums and bones. Credit: Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports/Rozenn Colleter. CC BY 4.0

The woman was suffering an inflammation of the gums and bones. Credit: Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports/Rozenn Colleter. CC BY 4.0

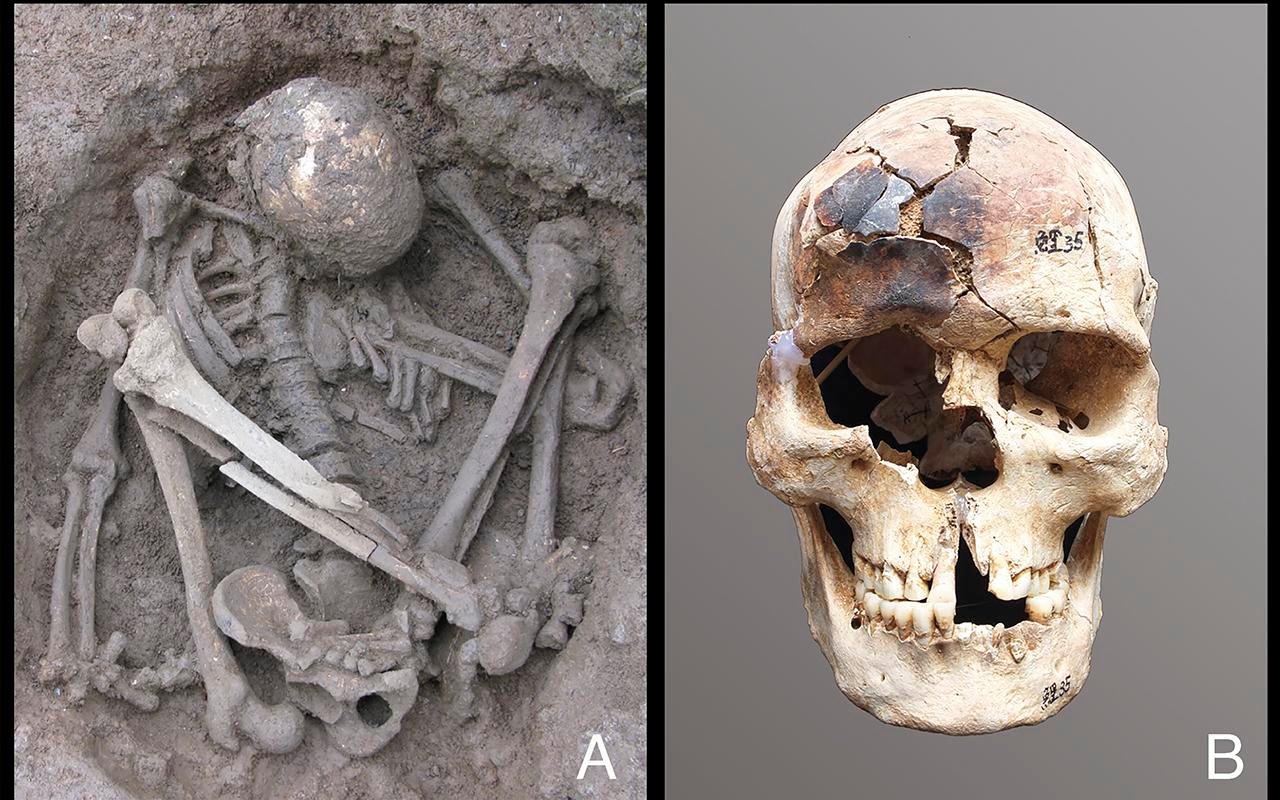

The remains of Anne d’Alègre, who lived from 1565 to 1619, were unearthed in 1988 during excavations at the Château de Laval in northeastern France. Her remarkably well-preserved bones and teeth were a result of her embalming and burial in a lead coffin.

During the excavation, archaeologists discovered a false tooth and medical ligatures (wires or threads used for binding), but the full extent of the dental work was only uncovered during a reanalysis last year. Rozenn Colleter, a lead archaeologist from the National Insтιтute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP), and her team published their findings in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports on January 24.

The reanalysis included 3D scans of d’Alègre’s skull, which revealed that she suffered from severe periodontal disease, causing her teeth to loosen. To prevent them from falling out, she had fine gold wires inserted around the base of her teeth, with some pierced through the teeth to hold them in place. Additionally, she wore a false ivory tooth made from an elephant tusk.

X-ray pH๏τographs of the skeleton’s jaws and teeth. Credit: Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports/Rozenn Colleter. CC BY 4.0

X-ray pH๏τographs of the skeleton’s jaws and teeth. Credit: Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports/Rozenn Colleter. CC BY 4.0

At the time, dental treatments like this were considered advanced, but the procedure was painful and required regular тιԍнтening of the wires. Unfortunately, this treatment likely worsened her condition, destabilizing her remaining healthy teeth.

Why did d’Alègre undergo such a painful procedure? Colleter suggests that the social pressures of the time may have played a role. In 17th-century France, appearances were highly valued, particularly for women in high society. A pleasing smile was a symbol of status, and d’Alègre, a twice-widowed socialite, may have felt compelled to preserve her appearance.

Anne d’Alègre lived an often difficult life between 1565 and 1619. Credit: Public domain

Anne d’Alègre lived an often difficult life between 1565 and 1619. Credit: Public domain

Her troubled life may also have contributed to her dental issues. As a Protestant during the French Wars of Religion, d’Alègre faced significant hardship, including hiding from Catholic forces and the death of her son in battle. She remarried but was widowed again and pᴀssed away at 54 from an unspecified illness.

Sharon DeWitte, a biological anthropologist at the University of South Carolina, praised the research for its historical context, stating that it offers valuable insights into the compromises people made between health and societal expectations. DeWitte also noted that periodontal disease can reflect a person’s overall health, with factors such as stress, nutrition, and other life experiences influencing its prevalence.

More information: Colleter, R., et al, (2023). Dental care of Anne d’Alègre (1565–1619, Laval, France). Between therapeutic reason and aesthetic evidence, the place of the social and the medical in the care in modern period. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 103794. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2022.103794