Archaeologists working in the Caucasus Mountains in southern Russia discovered a revolutionary artifact that challenges ᴀssumptions held for centuries about Neanderthal technological skill.

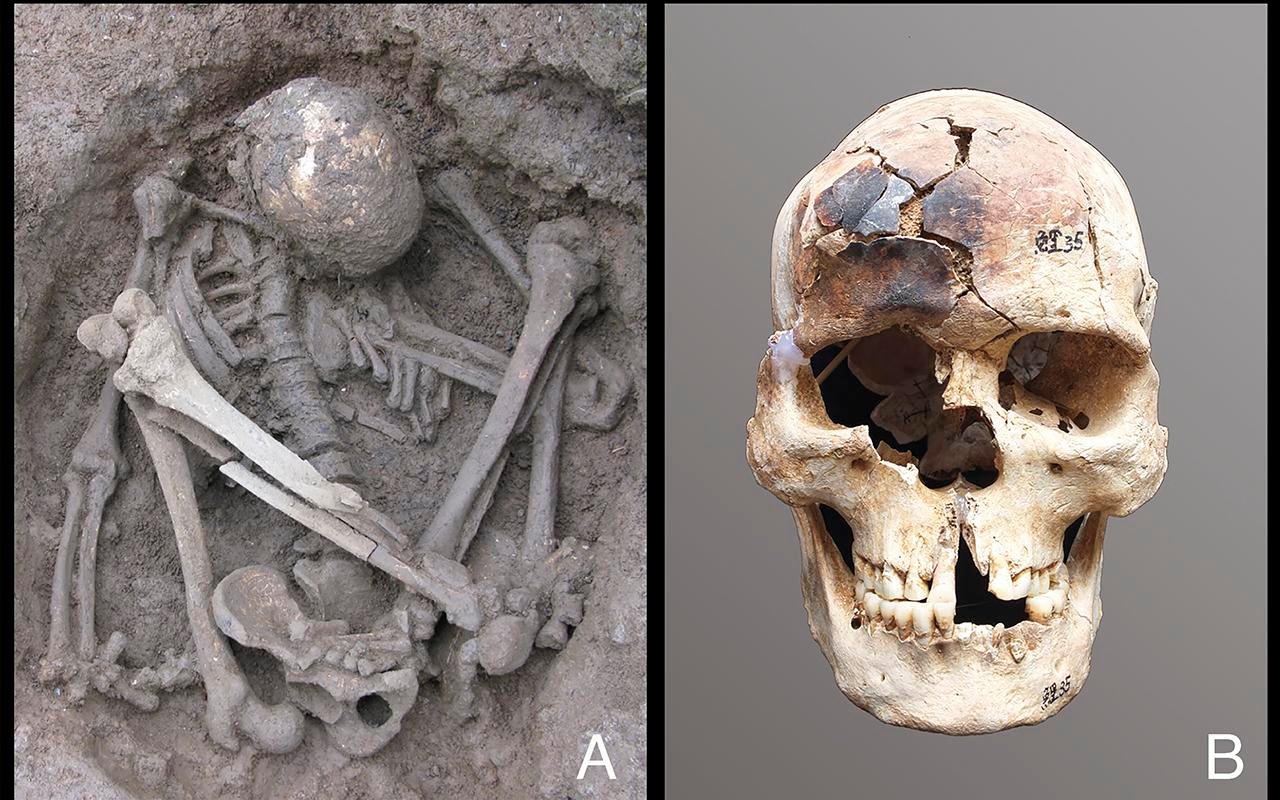

Scientists discover oldest known human viruses in 50,000-year-old Neanderthal remains. Credit: Paul Hudson, Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Scientists discover oldest known human viruses in 50,000-year-old Neanderthal remains. Credit: Paul Hudson, Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

A bone spear point that measures 9 centimeters in length, recovered from Mezmaiskaya Cave in the North Caucasus region, is now confirmed to be the oldest of its kind discovered in Europe. Dating back 70,000 to 80,000 years, the artifact is a robust indicator that Neanderthals independently developed complex hunting tools long before modern humans.

The spear tip was originally discovered in 2003 among animal bones, stone tools, flint debris, and the remnants of a hearth. Despite being overlooked for decades, it has now undergone detailed analysis with computed tomography, high-powered microscopy, and spectroscopy. These techniques revealed that the spear was carefully crafted from the leg bone of a bison. It was sharpened with stone tools, hardened with fire, and attached using tar—an adhesive made by the complex process of controlled heating of organic material—to bond it to a wooden shaft.

Paleoarchaeologist Liubov V. Golovanova, who led the study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, and her team described the spear tip as “a unique pointy bone artifact.” As the archaeologists wrote, “The bone point does not need to have a sharply pointed (needle-like) distal end (in contrast to bone awls), but it needs to have a strong, conical tip, symmetrical outlines, and a straight profile.”

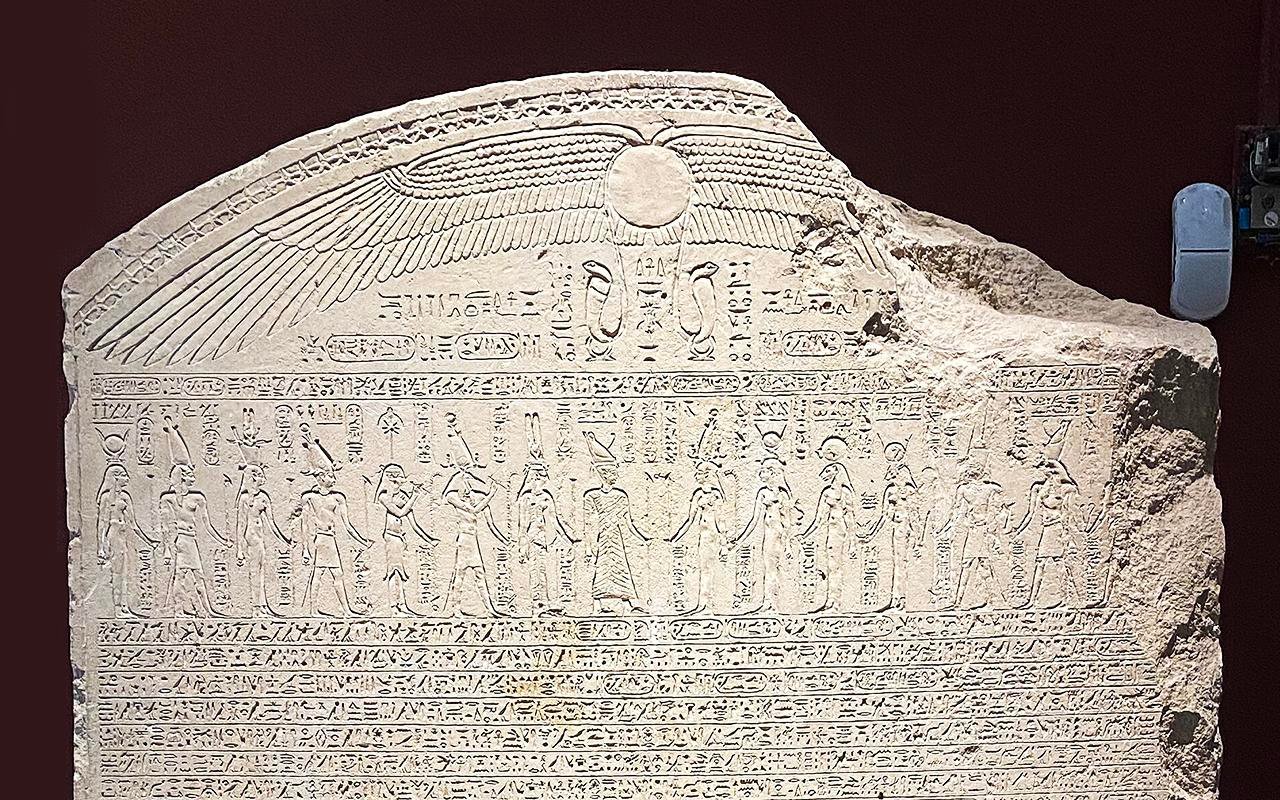

Credit: Pixabay, CC0 1.0

Credit: Pixabay, CC0 1.0

Microscopic damage marks, such as micro-fractures and cracks, attest to the fact that the spear was indeed in use during hunting. The absence of excessive wear, however, implies that it may have broken shortly after it was deployed—perhaps during its first deployment. Scientists even found traces showing that a Neanderthal artisan attempted to repair the spear by grinding down the damaged area.

The location of the find near a hearth in a natural hollow on a limestone slab gives a living picture of Neanderthal life. The cave was a long-term workshop used by generations of Neanderthals. They crafted tools and butchered animal prey such as birds, deer, bison, goats, and other animals there.

The spear tip’s aerodynamics and use of fire-hardened bone demonstrably show an understanding of engineering and hunting strategy. The research further explains how parallel grooves and polished surfaces on the artifact demonstrate intentional shaping for flight, similar to the type of projectiles used by later Homo sapiens. This find, however, predates European modern humans by at least 25,000 years.

One thing that is left unanswered, however, is why more bone tools like this have not survived. Scientists think that bone is far less durable than stone and may have decomposed over time, especially outside of protected environments like caves. Discoveries like this are thus rare but valuable.

More information: To view the original image and learn more about this discovery, you can visit this page on phys.org.

Publication: Golovanova, L. V., Doronichev, V. B., Doronicheva, E. V., Poplevko, G. N., Cleghorn, N. E., Kulkov, A. M., … Staroverov, N. E. (2025). On the Mousterian origin of bone-tipped hunting weapons in Europe: Evidence from Mezmaiskaya Cave, North Caucasus. Journal of Archaeological Science, 179(106223), 106223. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2025.106223