Archaeologists on Crete have revealed telling evidence that Bronze Age populations did not just give up on their ancient burial grounds—rather, they entombed them in complex rituals that reflected profound societal changes. In a paper recently published in the journal Antiquity, the researchers studied the Sissi cemetery, where around 3,800 years ago, the local community gathered in a symbolic and carefully orchestrated ceremony to “kill” their collective tombs.

The archaeological site of Sissi, seen from the north. The white dotted line indicates the limits of the cemetery (Zones 1 & 9) (© Belgian School at Athens, N. Kress). Credit: S. Déderix et al., Antiquity (2025)

The archaeological site of Sissi, seen from the north. The white dotted line indicates the limits of the cemetery (Zones 1 & 9) (© Belgian School at Athens, N. Kress). Credit: S. Déderix et al., Antiquity (2025)

This act was not an act of vandalism or abandonment but instead a public ritual that symbolized the end of an epoch—one that was shaped by centuries of communal burial traditions that had defined Cretan life. The cemetery of Sissi, located near the island’s north coast, offers a vivid impression of this process.

The Belgian School at Athens has led excavations at the site since 2007. Their findings show that around 1700 BCE, in an area known as Zone 9, the inhabitants dismantled their common tombs in a highly ritualized way. The tombs, which generations of one family had used for burials and communal rites, were deliberately cleared. Final burials were held in small pits or ceramic vessels, and subsequently, the walls of the tombs were dismantled, some of the remains partially crushed, and the earth leveled.

A communal feast followed. There were thousands of pottery fragments—cups, cooking pots, plates—all of the same date—scattered throughout the ground, a layer which unambiguously records a large event. The study’s authors believe this was not refuse but the remnants of a ritual gathering—an act of closure.

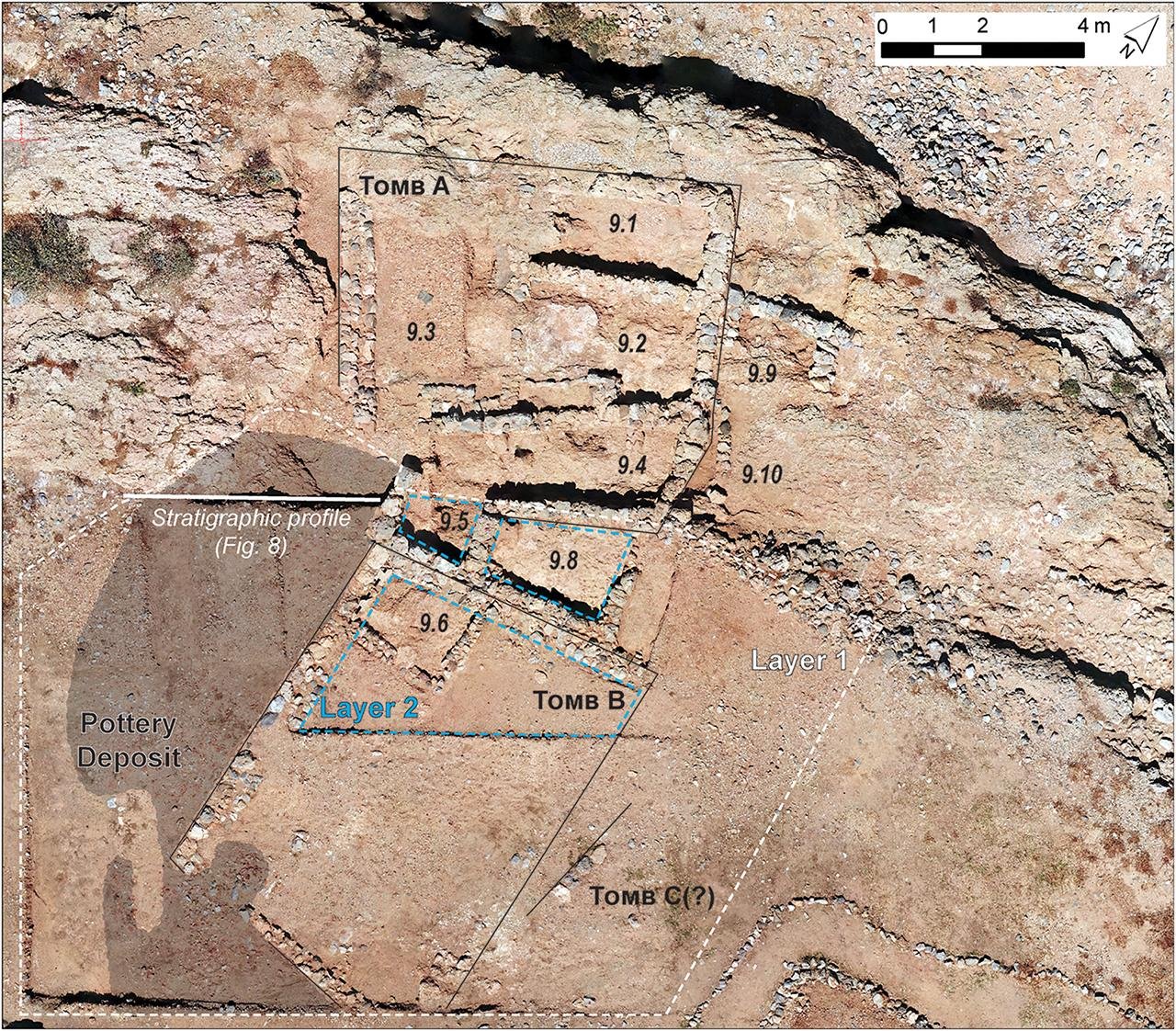

Zone 9 at Sissi (© Belgian School at Athens, N. Kress, modified). Credit: S. Déderix et al., Antiquity (2025)

Zone 9 at Sissi (© Belgian School at Athens, N. Kress, modified). Credit: S. Déderix et al., Antiquity (2025)

This ritual closure was then followed by the thorough burial of the site with soil and stones. Interestingly, later communities continued to refuse to disturb the ground, implying that a collective memory of its sacred nature persisted long after the site was abandoned.

This process, however, was not confined to Sissi. Comparable termination rites have been found elsewhere in Crete, for instance at Moni Odigitria and Kephala Petras, where tombs were emptied out, filled with stones, or sealed off, sometimes accompanied by feasting rituals of their own. Not all Minoan cemeteries, however, ended in such a dramatic act. In most areas, burial grounds simply fell out of use, though they were sometimes still visited for non-funerary rites.

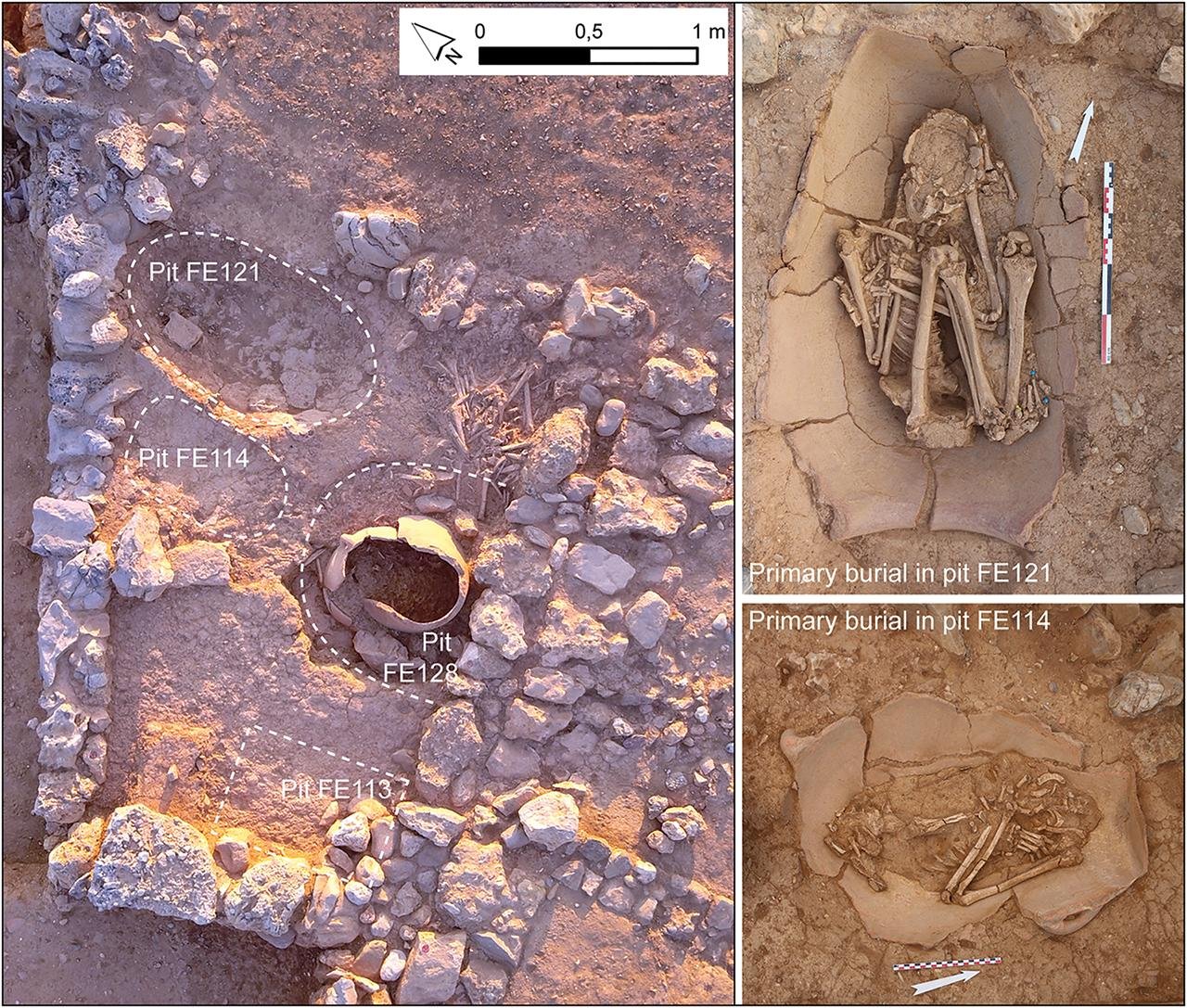

Compartment 9.8, with the location of Pits FE113, FE114, FE121 and FE128 (containing the pithos fragments labelled FE127) (left) and details of the primary burials in pits FE114 and FE121 (right) (© Belgian School at Athens, N. Kress, A. Schmitt). Credit: S. Déderix et al., Antiquity (2025)

Compartment 9.8, with the location of Pits FE113, FE114, FE121 and FE128 (containing the pithos fragments labelled FE127) (left) and details of the primary burials in pits FE114 and FE121 (right) (© Belgian School at Athens, N. Kress, A. Schmitt). Credit: S. Déderix et al., Antiquity (2025)

During the Middle Bronze Age (around 2050–1600 BCE), Crete was undergoing a fundamental transformation. With the rise of palatial centers like Knossos, there was a tendency toward centralization and individual status. As people were integrated into wider networks of political and religious activity, local practices like family tombs lost social significance. New ritual sites—mountain sanctuaries, caves, and palace-centered courtyards—started to replace cemeteries as the focal points for community gatherings.

The research team noted that collective tomb abandonment was neither sudden nor uniform. In some areas, usage was slowly declining, while in others, like Sissi, dramatic and deliberate closings took place.

Above all, recent excavation techniques, such as stratigraphic analysis and osteological study, have allowed archaeologists to uncover these complex stories. Earlier digs lacked such detailed methodologies, so it is not surprising that similar evidence may have been overlooked elsewhere. As more sites are excavated using new procedures, researchers expect to put together a more complete picture of how ancient Cretans responded to the social upheavals of their day.

More information: Déderix S, Schmitt A, Caloi I. The death of collective tombs in Middle Bronze Age Crete: new evidence from Sissi. Antiquity. Published online 2025:1-19. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.38