A team of researchers from the Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW) and the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) found dozens of hidden medieval inscriptions within the Cenacle in Jerusalem—long believed to be the location of the Last Supper.

The Hall of the Last Supper on Mount Sion. Credit: Heritage Conservation Jerusalem Pikiwiki Israel

The Hall of the Last Supper on Mount Sion. Credit: Heritage Conservation Jerusalem Pikiwiki Israel

With the help of advanced imaging techniques such as ultraviolet filters, Reflectance Transformation Imaging, and multispectral pH๏τography, the researchers captured nearly 30 inscriptions and nine drawings on the walls of the room. These marks were plastered over for centuries and rediscovered only in the 1990s when the room was being restored.

The findings, which were recently published in Liber Annuus, the yearbook of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, offer a glimpse into the lives of Christian pilgrims who visited the site between the 14th and 16th centuries.

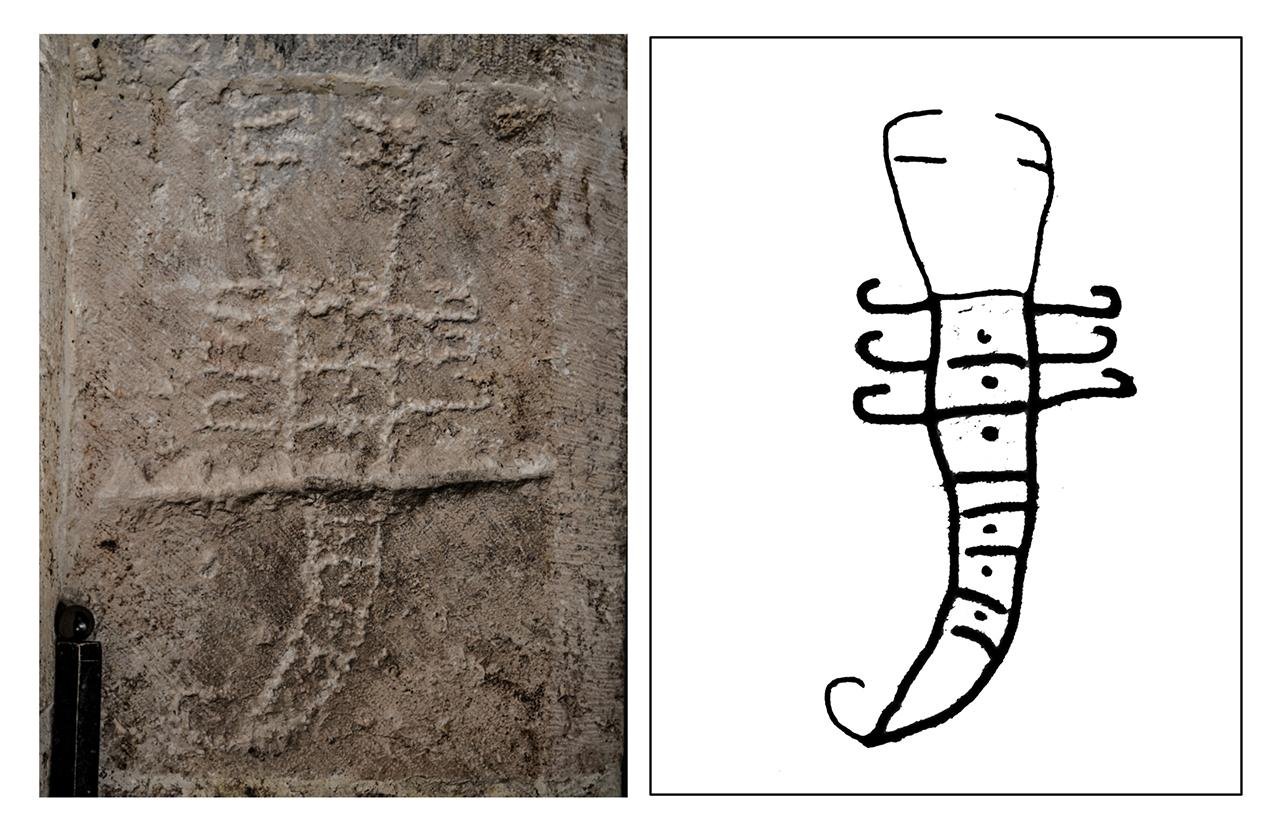

Carved Coat of Arms with the inscription “Altbach”. This image is almost identical to the coat of arms of the modern city of the same name in southern Germany. It appears to have been left by an unknown pilgrim from the local knightly family. Credit: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority

Carved Coat of Arms with the inscription “Altbach”. This image is almost identical to the coat of arms of the modern city of the same name in southern Germany. It appears to have been left by an unknown pilgrim from the local knightly family. Credit: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority

Among the discoveries is an Armenian inscription that reads “Christmas 1300.” It supports the controversial theory that Armenian King Het’um II could have reached Jerusalem after his army’s victory in the Battle of Wādī al-Khaznadār in Syria in 1299. The inscription, carved high on the wall in a style common among Armenian nobles, supports the king’s pilgrimage argument in history.

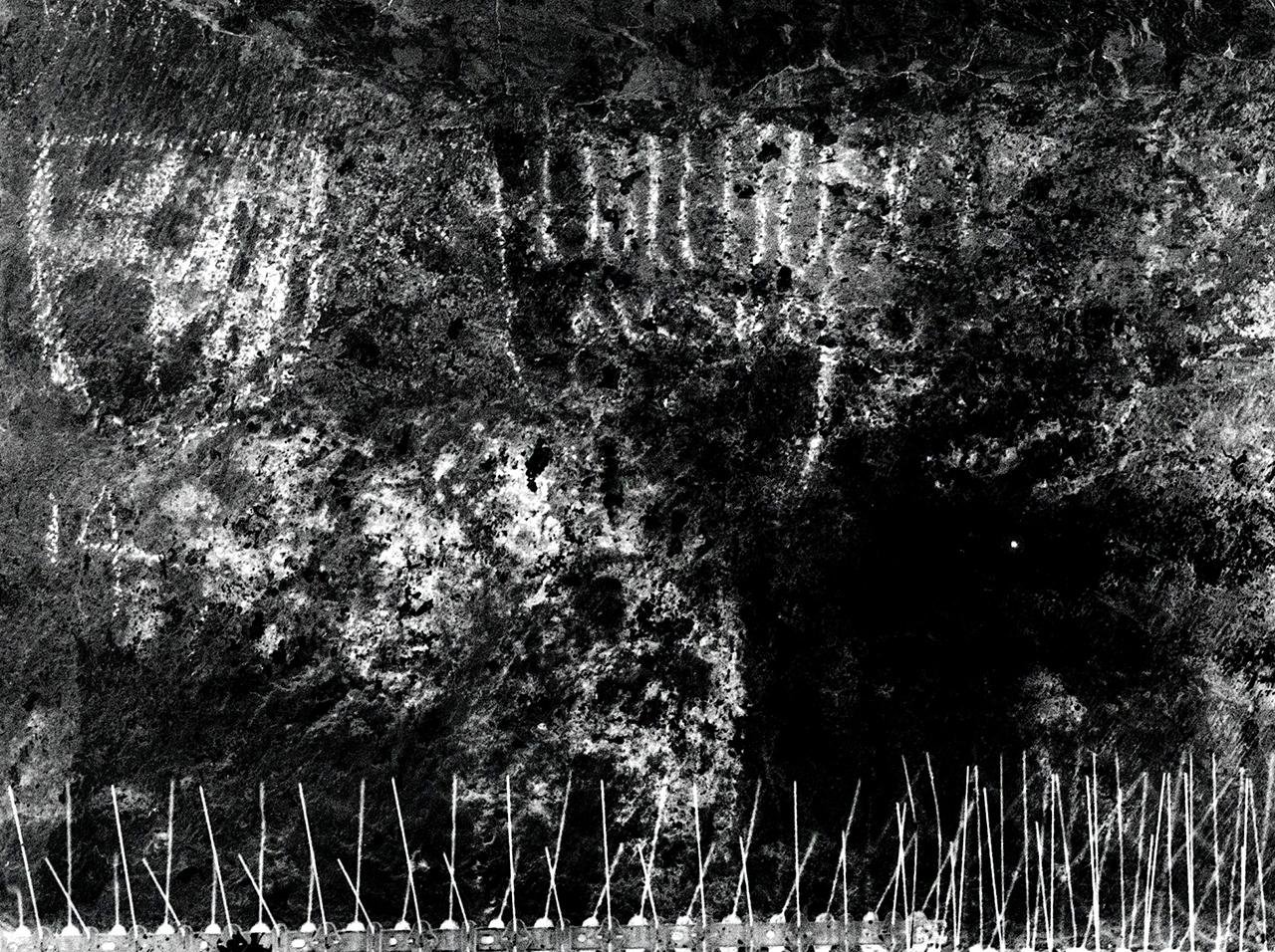

Digitally remastered black-and-white multispectral image of the “Teuffenbach” coat of arms from Styria. Directly below, the half-erased date 14.. can be seen. To the right are two further inscriptions: the monumental Armenian Christmas inscription and a Serbian inscription “Akakius”. Credit: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority

Digitally remastered black-and-white multispectral image of the “Teuffenbach” coat of arms from Styria. Directly below, the half-erased date 14.. can be seen. To the right are two further inscriptions: the monumental Armenian Christmas inscription and a Serbian inscription “Akakius”. Credit: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority

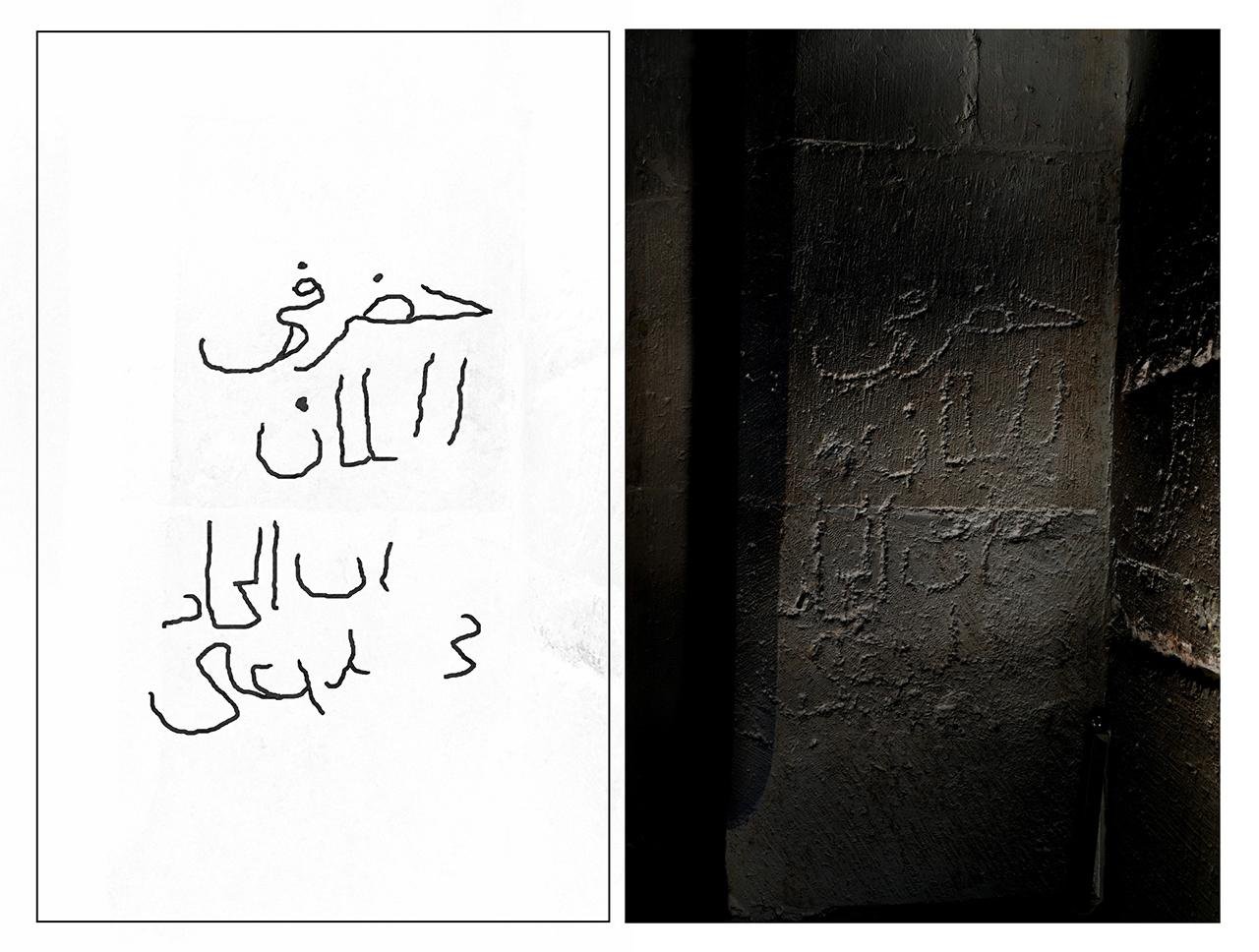

Another inscription, written in Arabic, ends with the words “…ya al-Ḥalabīya.” Scholars believe that it was written by a Christian woman from Aleppo—based on the feminine grammatical form.

The Cenacle, located on Mount Sion, is sacred to Christians, Jews, and Muslims. Christians believe it to be the site of the Last Supper. Jews and Muslims consider it to be the tomb of King David. The current building was built during the Crusader period and once formed part of a Franciscan monastery before the Ottomans expelled the friars in 1517.

Chiselled Inscription and scorpion drawing in honour of Sheikh Aḥmad al-ʿAǧamī. The Sheikh played an important role in the history of the Cenacle. On his insistence, in 1523 Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent expelled the Franciscans and turned the hall into a mosque. Credit: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority

Chiselled Inscription and scorpion drawing in honour of Sheikh Aḥmad al-ʿAǧamī. The Sheikh played an important role in the history of the Cenacle. On his insistence, in 1523 Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent expelled the Franciscans and turned the hall into a mosque. Credit: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority

Many inscriptions show the wide geographic spread of pilgrims. One of the names found is Johannes Poloner from Regensburg. He traveled to Jerusalem in 1421–22 and later wrote a book detailing his journey. There is also the coat of arms of Tristram von Teuffenbach, a Styrian nobleman, who traveled with Archduke Frederick of Habsburg in 1436.

Other notable mentions include Swiss knight Adrian I von Bubenberg, who is remembered for defending Bern, and Jacomo Querini of Venetian nobility. Even Franconian count Lamprecht von Seckendorff left his mark on the Cenacle’s stone.

While some may be surprised that pilgrims were allowed to leave their marks on such a holy site, the study suggests that the Franciscans may have permitted it. Some of the drawings are highly detailed and would have required hours to make. “The atтιтude of the Franciscans to this subject was ambivalent,” the researchers wrote in their article.

Chiselled Inscription and scorpion drawing in honour of Sheikh Aḥmad al-ʿAǧamī. The Sheikh played an important role in the history of the Cenacle. Credit: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority

Chiselled Inscription and scorpion drawing in honour of Sheikh Aḥmad al-ʿAǧamī. The Sheikh played an important role in the history of the Cenacle. Credit: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority

Even after the Franciscans were expelled, other people continued to add to the walls. One of the carvings, likely made during the Ottoman conquest, bears a dedication to Sheikh Aḥmad al-ʿAǧamī and a symbolic scorpion, symbolizing the shift in control.

The study offers a reminder of Jerusalem’s reputation as a spiritual crossroads. Far from being visited only by Western pilgrims, the Cenacle attracted visitors from Armenia, Syria, Austria, Switzerland, Germany, Serbia, and the Czech lands.

More information: Austrian Academy of SciencesPublication: Shai Halevi, Ilya Berkovich, Michael Chernin, Samvel Grigoryan, Arsen Harutyunyan, (2024)‚ The Holy Compound on Mount Sion – An Epigraphic Heraldic Corpus (Part 1): The Walls of the Cenacle‘, Liber Annuus 74, S. 331–74.