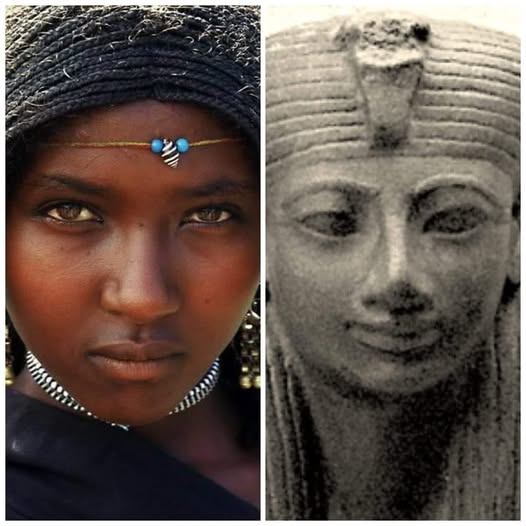

Hatshepsut was the Great Royal Wife of Pharaoh Thutmose II and the fifth Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, ruling first as regent, then as queen regnant from c. 1479 BC until c. 1458 BC. She was Kemet’s second confirmed queen regnant, the first being Sobekneferu/Nefrusobek in the Twelfth Dynasty.

Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut, daughter of King Thutmose I, became queen of Egypt when she married her half-brother, Thutmose II, around the age of 12. Upon his death, she began acting as regent for her stepson, the infant Thutmose III, but later took on the full powers of a pharaoh, becoming co-ruler of Egypt around 1473 B.C. As pharaoh—the sixth of the 18th dynasty— Hatshepsut extended Egyptian trade and oversaw ambitious building projects, most notably the Temple of Deir el-Bahri, located in western Thebes, where she would be buried. Depicted (at her own orders) as a male in many contemporary images and sculptures, Hatshepsut remained largely unknown to scholars until the 19th century. She is one of the few and most famous female pharaohs of Egypt.

Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power

Hatshepsut was the elder of two daughters born to Thutmose I and his queen, Ahmes. After her father’s death, 12-year-old Hatshepsut became queen of Egypt when she married her half-brother Thutmose II, the son of her father and one of his secondary wives, who inherited his father’s throne around 1492 B.C. They had one daughter, Neferure. Thutmose II died young, around 1479 B.C., and the throne went to his infant son, also born to a secondary wife. According to custom, Hatshepsut began acting as Thutmose III’s regent, handling affairs of state until her stepson came of age.

Did you know?

Hatshepsut was only the third woman to become pharaoh in 3,000 years of ancient Egyptian history, and the first to attain the full power of the position. Cleopatra, who also exercised such power, would rule some 14 centuries later.

After less than seven years, however, Hatshepsut took the unprecedented step of ᴀssuming the тιтle and full powers of a pharaoh herself, becoming co-ruler of Egypt with Thutmose III. Though past Egyptologists held that it was merely the queen’s ambition that drove her, more recent scholars have suggested that the move might have been due to a political crisis, such as a threat from another branch of the royal family, and that Hatshepsut may have been acting to save the throne for her stepson.

Hatshepsut as Pharaoh

Knowing that her power grab was highly controversial, Hatshepsut fought to defend its legitimacy, pointing to her royal lineage and claiming that her father had appointed her his successor. She sought to reinvent her image, and in statues and paintings of that time, she ordered that she be portrayed as a male pharaoh, with a beard and large muscles. In other images, however, she appeared in traditional female regalia. Hatshepsut surrounded herself with supporters in key positions in government, including Senenmut, her chief minister. Some have suggested Senenmut might also have been Hatshepsut’s lover, but little evidence exists to support this claim.

As pharaoh, Hatshepsut undertook ambitious building projects, particularly in the area around Thebes. Her greatest achievement was the enormous memorial temple at Deir el-Bahri, considered one of the architectural wonders of ancient Egypt. Another great achievement of her reign was a trading expedition she authorized that brought back vast riches–including ivory, ebony, gold, leopard skins and incense–to Egypt from a distant land known as Punt (possibly modern-day Eritrea).

Hatshepsut’s Death and Legacy

Hatshepsut probably died around 1458 B.C., when she would have been in her mid-40s. She was buried in the Valley of the Kings (also home to Tutankhhamum), located in the hills behind Deir el-Bahri. In another effort to legitimize her reign, she had her father’s sarcophagus reburied in her tomb so they could lie together in death. Thutmose III went on to rule for 30 more years, proving to be both an ambitious builder like his stepmother and a great warrior. Late in his reign, Thutmose III had almost all of the evidence of Hatshepsut’s rule—including the images of her as king on the temples and monuments she had built—eradicated, possibly to erase her example as a powerful female ruler, or to close the gap in the dynasty’s line of male succession. As a consequence, scholars of ancient Egypt knew little of Hatshepsut’s existence until 1822, when they were able to decode and read the hieroglyphics on the walls of Deir el-Bahri.