A revolutionary study in genetics has upended the long-standing belief that modern humans originated from a single continuous lineage. Instead, research conducted by a team at the University of Cambridge has now produced robust evidence suggesting that Homo sapiens is the result of a mixture between two ancient ancestral populations that diverged approximately 1.5 million years ago and reconnected approximately 300,000 years ago.

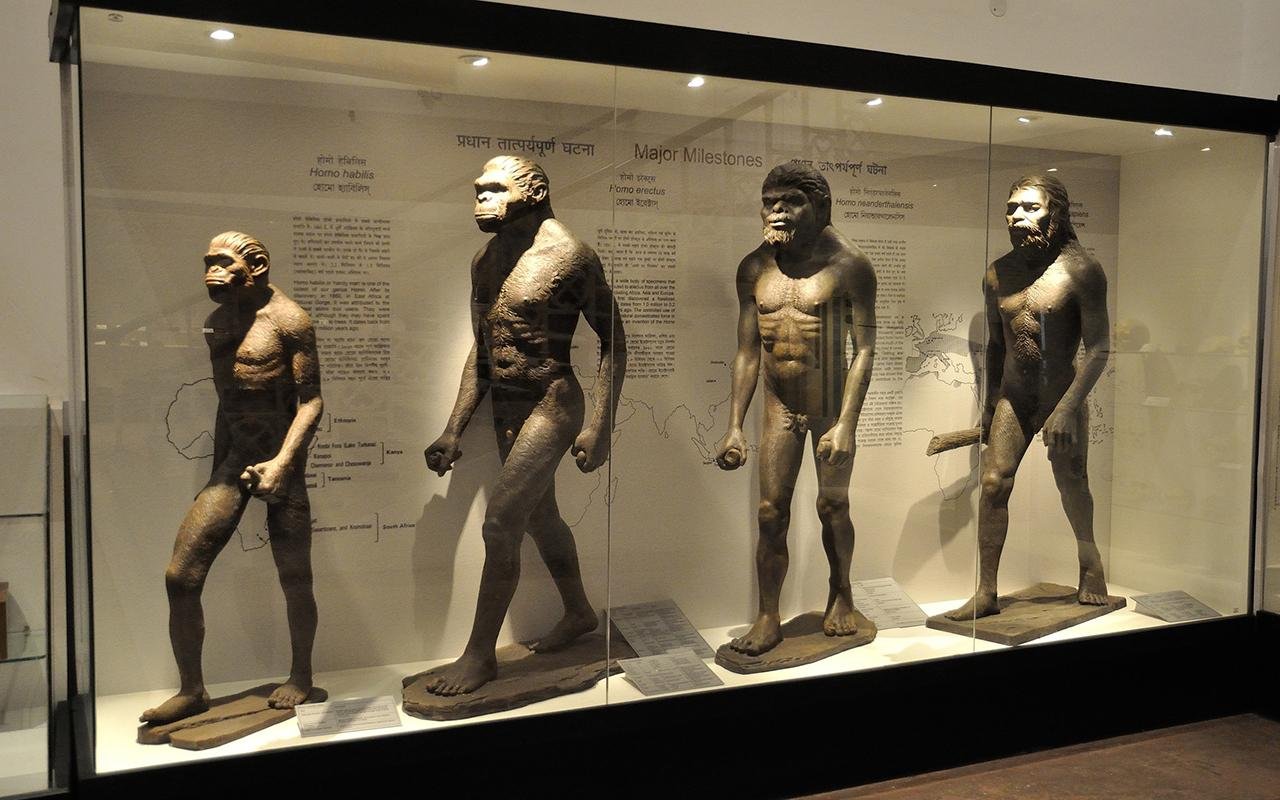

Human Evolution Gallery at Indian Museum Kolkata. Credit: Biswarup Ganguly

Human Evolution Gallery at Indian Museum Kolkata. Credit: Biswarup Ganguly

The research, which was published in the journal Nature Genetics, contradicts the view that modern humans evolved from a single ancestral population of humanity in Africa between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago, instead putting forward a considerably more complicated evolutionary history.

Dr. Trevor Cousins, the study’s first author from Cambridge’s Department of Genetics, said: “For a long time, it’s been ᴀssumed that we evolved from a single continuous ancestral lineage, but the exact details of our origins are uncertain.”

Using advanced genomic analytical methods, the scientists identified two primary ancestral groups—Population A and Population B—that split approximately 1.5 million years ago. Population A underwent a severe bottleneck, shrinking to a very small population size, then gradually growing over the next million years. This group would later contribute roughly 80% of the genetic material to modern humans and was also the ancestral lineage of Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Early Humans’ Burial. Credit: Laura Blankenship, via Flickr

Early Humans’ Burial. Credit: Laura Blankenship, via Flickr

In contrast, Population B was distinct until about 300,000 years ago, when the two populations interbred. It was through this event that approximately 20% of the DNA of modern humans originated from Population B.

According to co-author Professor Richard Durbin, also from Cambridge’s Department of Genetics, “Our research shows clear signs that our evolutionary origins are more complex, involving different groups that developed separately for more than a million years, then came back together to form the modern human species.”

Although Neanderthal DNA represents about 2% of the genome of non-African modern humans, the ancient interbreeding provided a more substantial contribution to the modern gene pool. Notably, Population B genes were highly concentrated in regions of the genome ᴀssociated with brain function and neural processing, providing further evidence that this genetic exchange may have played a crucial role in the development of human cognition.

According to the researchers, some of the genes from Population B may have been less compatible with the predominant genetic background. This hints at a process known as purifying selection, where natural selection removes harmful mutations over time.”

The researchers used a computational algorithm known as cobraa, which models how ancient human populations split apart and later merged back together. In contrast to prior studies, which relied on extracting DNA from ancient fossils, this method analyzed modern human DNA, utilizing the 1,000 Genomes Project and Human Genome Diversity Project data in this analysis.

A reconstruction of an elderly Neanderthal man. Credit: Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann

A reconstruction of an elderly Neanderthal man. Credit: Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann

Overall, the findings from this research illustrate new aspects of the evolutionary history of Homo sapiens, raising interesting questions regarding our ancestry. Fossil record evidence from Africa and elsewhere shows that species such as Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis were present during the period in question, and either could be candidates for those ancestral populations. However, the analysis of modern genetic information alone cannot definitively determine which fossil groups belong to Population A or B.

“What’s becoming clear is that the idea of species evolving in clean, distinct lineages is too simplistic,” Cousins said. “Interbreeding and genetic exchange have likely played a major role in the emergence of new species repeatedly across the animal kingdom.”

Beyond illuminating human ancestry, the study’s methods could transform how scientists study evolution in other species. The team used their model on genetic data from other species, including bats, dolphins, chimpanzees, and gorillas, and found support for evidence of ancestral population structure in some groups but not others.

In the future, the researchers plan to improve their model to account for more gradual genetic exchanges (not just sharp splits and reunions). They will also explore how the findings align with fossils that imply early human populations were more diverse than previously considered.

“The fact that we can reconstruct events from hundreds of thousands or millions of years ago just by looking at DNA today is astonishing,” said co-author Dr. Aylwyn Scally. “And it tells us that our history is far richer and more complex than we imagined.”

More information: Cousins, T., Scally, A. & Durbin, R. (2025). A structured coalescent model reveals deep ancestral structure shared by all modern humans. Nature Genetics. doi:10.1038/s41588-025-02117-1