Criss-crossed by a network of canals and dotted with harbours, wharves, temples and tower-houses – all joined together by a network of ferries, bridges, and pontoons – the city controlled most of the maritime traffic coming into Egypt from the Mediterranean. Goods would be inspected and taxed at the customs administration centre, and then carried on for distribution further inland, either at Naukratis – another trading port that lay almost 50 miles further up the Nile – or via the Western Lake, which was connected by a water channel to the nearby town of Canopus and offered access to many other parts of the country.

Although Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus are mentioned by many of the great chroniclers of antiquity, from Herodotus to Strabo and Diodorus, most detailed knowledge of their existence was feared to have been permanently lost.

<ʙuттon class="open-lightbox dcr-4tmywn" type="ʙuттon" data-element-id="34f8ef29-9e44-4573-bb2e-1fec61961689" aria-haspopup="dialog">

View image in fullscreen A recreation of what the city may have looked like. PH๏τograph: Yann Bernard © Franck Goddio / Hilti Foundation.

Before 1933, when an RAF commander flying over Abu Qir glimpsed ruins in the water, most historians believed Thonis and Heracleion to have been two separate conurbations, both of which were situated on the current Egyptian mainland. The pilot’s sighting, however, kicked off a whole new era of offshore research. By the turn of the century a team from the European Insтιтute for Underwater Archaeology – originally attracted to the bay by the presence of French warships that sunk in the late 18th century – had created a series of maps sketching out the ancient topography of the region.

These charts – and the painstaking work of underwater excavation that has followed – relied upon hi-tech survey techniques and tireless human effort. The waters here are murky and visibility is low; in the aftermath of storms, “the sea is all stirred up, and charged with floating sand and mud that makes it difficult for us divers to see what is going on,” explained one researcher.

Archaeologists had to begin with side-scan sonar, directing pulses of sound energy at the seabed and then analysing the echo to establish the changing depth of the ocean floor. A nuclear magnetic resonance magnetometer, which can detect localised anomalies in the earth’s magnetic fields, was then used to identify geological faultlines caused by the weight of long-submerged buildings pressing down upon and fracturing layers of sediment, and to pinpoint the presence of large objects.

<ʙuттon class="open-lightbox dcr-1sv232j" type="ʙuттon" data-element-id="0a79a842-4998-4811-a830-528558af3f4b" aria-haspopup="dialog">

View image in fullscreen The 5.4 metres tall statue of the god Hapy. PH๏τograph: Christoph Gerigk/Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation

With the most promising excavation spots now fixed, scuba divers were sent in. They carried water-dredges: huge underwater vacuum-cleaners that hoover away overlying blankets of sand and expose the archaeological layers beneath. The biggest items, such as building fragments and colossal statues – a Ptolemaic king and queen, each five metres high, among them – were the easiest to find and resurrect from the seabed, but smaller and more eclectic gems soon followed, including goblets, figurines, ritual pails, and 13 limestone animal sarcophagi.

One by one, each artefact was catalogued, pH๏τographed, and then – if safe to do so – winched up to the deck of the Princess Duda research boat before being subjected to further analysis back on land. Together, they have transformed our understanding not just of Thonis-Heracleion, but of the nature of Egypt and its interactions with the Hellenic world at the time. “Some of these objects are completely unique, of great historical or artistic importance,” Mᴀsson-Berghoff told the Guardian. “They push us to think anew.”

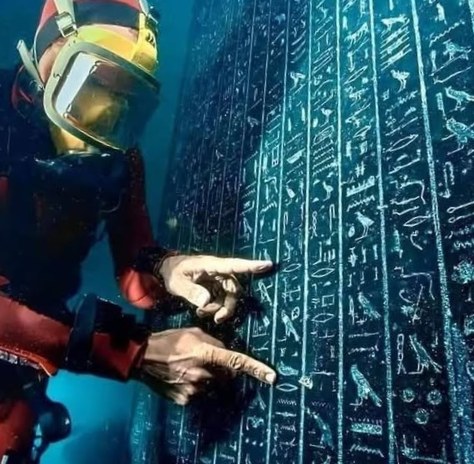

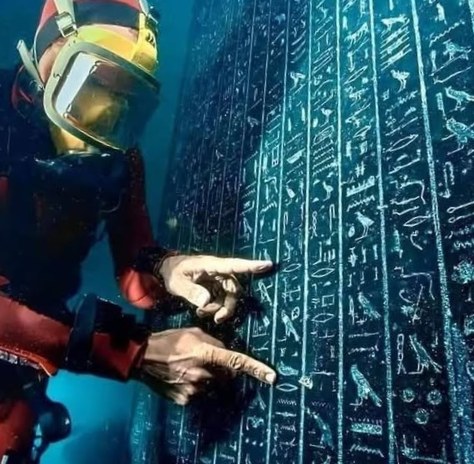

The Decree of Sais, for example – a magnificent black stele that stands two metres high and is carved with perfectly preserved hieroglyphics from the early fourth century BC – was unearthed on the site of a temple to supreme god of the Egyptians, Amun-Gereb, at Thonis-Heracleion. The stele reveals some of the intricacies of contemporary taxation in Egypt: “His Majesty [Pharaoh Nectanebo I] decreed: Let there be given one-tenth of the gold, of the silver, of the timber, of the processed wood and of all things coming from the sea of the Hau-Nebut [the Mediterranean] … to become divine offerings to my mother Neith,” reads its edict.

But the stele has done more than flesh out our understanding of ancient Egyptian tariffs. Its discovery has also helped solve a long-running mystery: by comparing it to other inscribed monuments, experts were able to determine that Thonis and Heracleion were not, as previously believed, two different towns, but rather one single city known by both its Egyptian and Greek name respectively.

The interplay between Pharaonic and Greek societies in Thonis-Heracleion is a constant feature of the city’s remnants: Hellenic helmets were nestled in the seabed alongside their Egyptian counterparts, as were Cypriot statuettes and incense burners, Athenian perfume bottles, and ancient anchors from Greek ships.

<ʙuттon class="open-lightbox dcr-4tmywn" type="ʙuттon" data-element-id="3a052272-023e-4438-b132-a15f0e36a593" aria-haspopup="dialog">

View image in fullscreen This stele reveals that Thonis (Egyptian) and Heracleion (Greek) were the same city. PH๏τograph: Christoph Gerigk/Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation

Nowhere was this cross-cultural pollination more evident than in the realm of religion, particularly during the rise of the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt, where a succession of foreign-born rulers sought to justify their power in the eyes of the Egyptian people by demonstrating their affinity with Pharaonic traditions.

One object recovered from the water is a 2,000-year-old stone figurine of Cleopatra III: a Ptolemaic queen, but depicted as the Egyptian goddess Isis and sculpted in a style that combines both local and Hellenic aesthetics.

Drowned worlds: Egypt’s lost cities

Among the most beguiling of Thonis-Heracleion’s remains are the artefacts ᴀssociated with the city at play. The annual celebration of the Mysteries of Osiris, marked all over ancient Egypt, involved the preparation – in the secrecy of the temples – of two figures of Osiris, god of the underworld and resurrection: one made of soil and barley, the other of expensive materials including ground-up semi-precious stones.

In Thonis-Heracleion, the former was placed in a granite tank and nurtured with Nile water until it germinated. It was then placed in a papyrus barge alongside 33 other vessels; the whole flotilla was illuminated by 365 oil lamps – one for each day of the year – and eventually sailed down to the nearby settlement of Canopus. As well as an 11-metre sycamore vessel that would have been used in this procession, archaeologists have unearthed several small lead replicas of the papyrus boats, thrown into the water as votive offerings by onlookers.

These finds offer a rare glimpse into the practice of ancient ritual, rather than just the liturgical representation of it. In Mᴀsson-Berghoff’s words, they provide a connection to the “materiality” of religion in Thonis-Heracleion. That’s important because, while the items dredged up so far from the bottom of Abu Qir bay tell a remarkable story of a city that could have vanished completely from our consciousness, it is, for now at least, very much a selective story. Those working on it today are well aware of its holes.

<ʙuттon class="open-lightbox dcr-4tmywn" type="ʙuттon" data-element-id="631722de-7489-4841-897b-5fac224fd1ba" aria-haspopup="dialog">

View image in fullscreen Archaeologists have so far only discovered a fraction of the city. PH๏τograph: Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio / Hilti Foundation

“My hope is that future discoveries will enable us to shed more light on the lives of ordinary people,” says Mᴀsson-Berghoff, who points out that while we know more than ever about Thonis-Heracleion’s rulers and priests, it is much harder to picture the mudbrick homes and daily lives of those who served them and kept the busy port operating smoothly.

Today, 95% of the area’s urban footprint remains to be explored; perhaps there are objects yet to be found that can enrich our understanding of how cargo unloaders, cleaners and cloth-sewers experienced their city. “What we know now is just a fraction,” observes Franck Goddio, director of the ongoing excavations. “We are still at the very beginning of our search.”

By the second century BC, Thonis-Heracleion’s era of pomp and prestige was already fading. Further along the coast, the new metropolis of Alexandria was rapidly establishing itself as Egypt’s preeminent port, while the hybrid foundation of land and water upon which Thonis-Heracleion was built had begun to feel less secure. It wasn’t a single natural disaster – an earthquake, tsunami, rising sea levels, or subsidence – that doomed the city, but rather a combination of them all.

At the end of the century, probably after a severe flood, the central island – already sagging under the weight of the main temple buildings – succumbed to liquefaction. In what must have been a terrifying experience, the hard clay soil turned to liquid in moments and the buildings atop it collapsed swiftly into the water. The supply of pottery and coins into Thonis-Heracleion appears to have ended at this point; a few hardy residents clung on to their homes throughout the Roman period and even into the beginning of Arab rule, but the last vestiges of the city sunk below the sea at the end of the eighth century.

At a time of looming ecological catastrophe, it is perhaps unsurprising that we should find the tale of Thonis-Heracleion so fascinating. Its rediscovery is a testament to advanced technology and human ingenuity, but the city’s fate – and the eerily inanimate memories of a long-forgotten urban life left behind – are a reminder of how fragile many of our own contemporary cities are.

Venice, arguably Thonis-Heracleion’s closest modern cousin owing to its siting on a lagoon and its famed network of waterways, is sinking; Egypt’s Mediterranean coastline remains one of the places on earth most vulnerable to rising sea levels, and even the most optimistic projections of global temperature increases could still displace millions in the region from their homes.

Hapy’s reawakening from the seabed, a millennium in the making, is a unique window to our urban past. The struggle continues to ensure he and his city are not also a vision of our future.

The Egyptians: A Radical Story, by Jack Shenker, is published by Allen Lane (£15.99); buy it for £11.19 here. Sunken Cities, an exhibition of artefacts found at Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus, is at the British Museum until 27 November 2016

Please share your stories of other ‘lost cities’ throughout history in the comments below. F ollow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join in the discussion