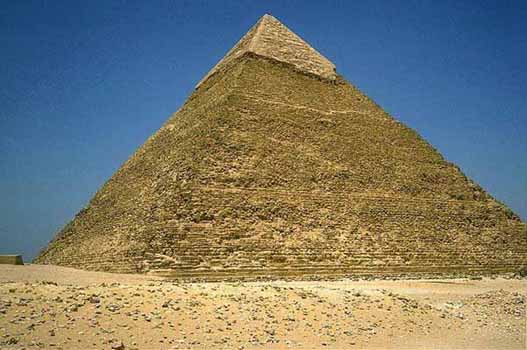

Pyramid of Khafre – Chepren

Giza Plateau – Pyramid of Khafre is in the Middle with a Limestone Capstone

Original name: Khafre is greatest

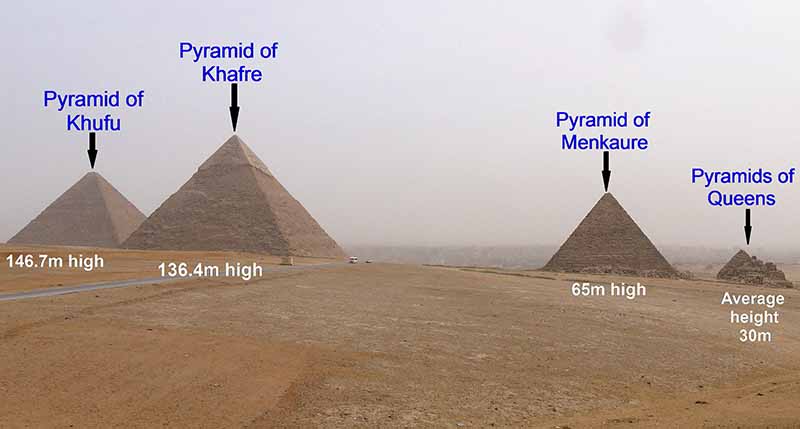

Original height: 143.5 m / 478.3 ft

Present day height: 136.4 m / 454.7 ft

Base length: 215.25 m / 717.5 ft – 11 acres

Angle of inclination: 53° 10′

Estimated volume: 1,659,200 m3 / 2,168,900 cu. yd

Date of construction: 4th dynasty, c. 2570 BC

Average Weight of Individual Blocks of Stone:

2.5tons, some of the outer casing blocks of stone weigh in at 7 tons

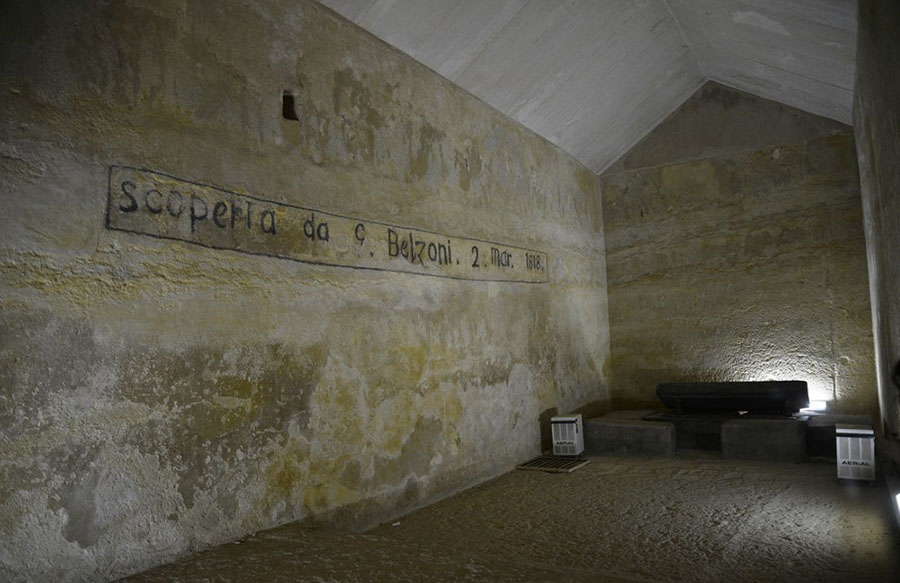

There is no evidence that anyone was ever buried in the main chamber.

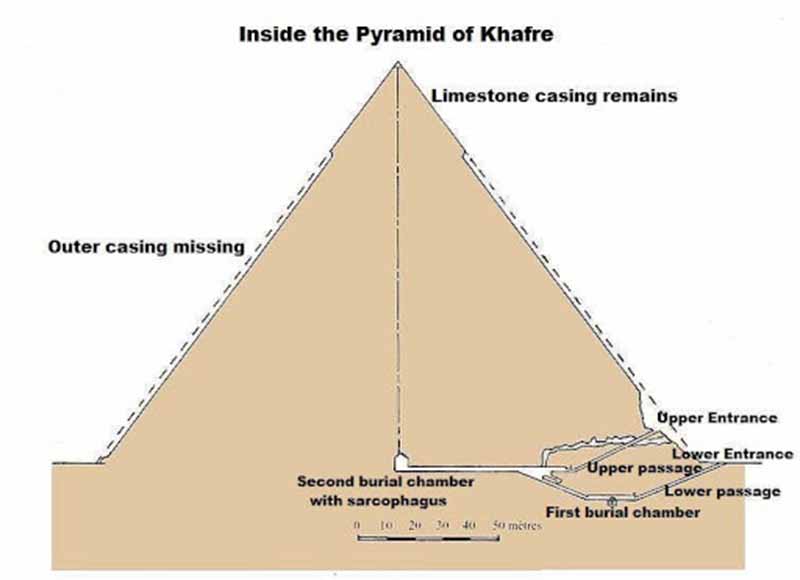

No inscriptions have been found in the pyramid, however there is a sarcophagus in the main chamber. There are two entrances that lead into the pyramid which are placed one directly above the other. The upper entrance is 50 feet (15m) above the ground. This is the one that is used for entrance now. A narrow pᴀssage leads into a large limestone chamber. This pᴀssageway descends at a 25 degree angle to the chamber. The walls are lined with red granite. This inner chamber is quite large, 46.5′ x 16.5′ x 22.5′ (14.2m x 5m x 6.9m). The roof of the chamber is set at the same angles as the pyramid face.

This is designed to take the weight of the pyramid, as is the relieving chambers in Khufu’s pyramid. Apparently the roof designed this way has worked, the pyramid has not collapsed.

The lower corridor is directly under the upper corridor. This lower corridor once contained a portcullis, which could be let down to prevent entry. This corridor declines on the same angle as the upper and eventually joins into the upper. Once joined, the pᴀssageway leads into the inner chamber.

Located in the lower pᴀssage is a burial chamber that is apparently unfinished and unused. It is in the bedrock under the pyramid. The pᴀssageway leads through this chamber and joins the upper corridor.

Khafre’s pyramid is hardly smaller than the one of his father, Khufu. As it has a more elevated position and its sides have a steeper angle of inclination, it even appears to be the larger in size. It is the only pyramid that still has parts of its outermost layers of Tura limestone.

The most distinctive feature of Khafre’s Pyramid is the topmost layer of smooth stones that are the only remaining casing stones on a Giza Pyramid.

Khafre whose older brother Djedefre died after a few years of governance, dreamed of having the biggest pyramid ever, even bigger than the one of Cheops, his ᴅᴇᴀᴅ father. His plans failed.

The pyramid contains 2 known chambers. One chamber is subterranean, carved into the very bedrock. The other has its floor carved into the bedrock while its upper walls and ceiling pierce into the base of the pyramid.

Descending steps

Descending steps

Burial Chamber – 46.5 ft. long and 16.5 ft. wide – pointed ceiling.

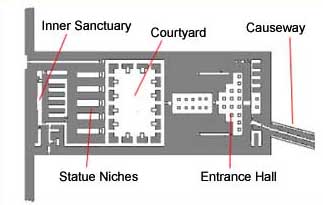

The causeway enters the mortuary temple near the south end of its front facade.

The entrance to the mortuary temple in the east led through to a small antechamber adorned with a pair of monolithic pink granite pillars. About the entrance area were a few small chambers (two granite chambers immediately to the left of the entrance, and at the other end of a short corridor running along the front of the temple, four more chambers lined with alabaster) that are thought to have been storage annexes or serdabs. Ricke, in his investigation of the mortuary temple, found this area strikingly similar to the valley temple, and considered it a kind of repeтιтion. He designated this area as the “ante-temple” (Vortempel) and the remaining area of the mortuary temple as the “worship temple” (Verehrungstempel).

This antechamber in turn led into the entrance hall itself where there were twelve more similar pairs of pillars to those in the antechamber. This entrance hall had an original ground plan of an inverted T. Hence, the first part of the entrance hall was transverse, with recessed bays. It led in turn to a rectangular section. Off of the transverse part of the hall, two long, narrow chambers branched off from either end, and it has been suggested that huge statues of the king once graced these dim pᴀssages.

After the entrance hall there is a large, open courtyard situated in approximately the middle of the temple. Paved in slabs of alabaster and oriented north-south, along its sides runs a covered ambulatory with a flat limestone roof made of slaps supported by broad pillars of pink granite. The lower part of this ambulatory was formed by a dado in red granite and limestone.

It was covered by brilliantly colored reliefs of which only fragments remain. Ricke thought that the ambulatory was fronted by 3.75 meter high statues of Khafre sitting on his throne overlooking the courtyard, but Lehner thinks these were standing statues of the ruler. Lehner bases his belief on the discovery of a small statuette in the workshops west of the pyramid. This artifact shows the ruler, wearing the crown of Upper Egypt, standing in front of a kind of pillar. The remains of a small canal suggest that it was drainage for an altar that stood in the middle of the courtyard.

A door in the west side of the ambulatory communicated with five, long chapels (actually niches) that also originally housed statues of the king. Another narrow corridor opens from the southwest corner of the courtyard and led to an offering hall located in the west part of the temple. The hall was a narrow, long room oriented north-south (in contrast to later mortuary temples) with a false door positioned on the west wall, precisely on the pyramid’s long axis. Between the five cult chapels and the offering hall, a group of five storage rooms were provided for cult vessels and offerings used during various ceremonies.

A stairway in the northeast corner of the temple led up to the roof terrace, while in the northwest corner of the courtyard, another corridor led to the paved pyramid enclosure.

Though all of them had been plundered apparently in antiquity, there were five boat bits discovered outside of the mortuary temple. Two of these stood on the north of the temple, while three were to its south.Another pit may have been planned. All of these were carved into the rock in the shape of a boat. Two of the pits still retained their roofing slabs, though all of the pits had been looted, probably during antiquity.

The valley temple of Khafre’s Giza complex, which is one of the best preserved Old Kingdom temples in Egypt. As a masterful work of ancient Egyptian monumental architecture, it was cleared of sand and in 1869 this temple, along with other monuments at Giza, became the backdrop for the ceremonial opening of the Suez Canal.

The temple was fronted on the east by a large terrace paved with limestone slabs, through which two causeways led from the Nile canal. Just about in the middle of the terrace, fragments of what may have been a small, simple, wood and matting structure was unearthed that may have been the location of a statue depicting Khafre. However, others believe that this was a tent used for purification purposes, though known examples of such a structure are only found in a few private tombs.

In 1995, Zahi Hawᴀss re-cleared the area in front of the Valley temple and in doing so, discovered that the causeways pᴀssed over tunnels that were framed with mudbrick walls and paved with limestone. These tunnels have a slightly convex profile resembling that of a boat. They formed a narrow corridor or canal running north-south. In front of the Sphnix Temple, the canal runs into a drain leading northeast, probably to a quay buried below the modern tourist plaza.

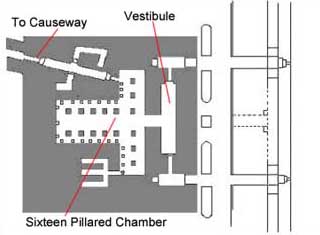

The causeways connected the Nile canal with two separate entrances on the Valley temple facade that were sealed by huge, single-leaf doors probably made of cedar wood and hung on copper hinges. Each of these doorways were protected by a recumbent Sphinx. The northern most of these portals was dedicated to the goddess Bastet, while the southern portal was dedicated to Hathor.

The temple was laid out in almost a square ground plan. It is situated just next to the Great Sphinx and its ᴀssociated temple. Not surprisingly, since the valley temple was a gateway or portal to the whole complex, it is very similar to the fore part of Khafre’s mortuary temple. Its core wall was built of huge blocks that sometimes weighed as much as one hundred and fifty tons. This inner core was then covered by pink granite slabs, a material used extensively throughout the complex that was quarried near Aswan far to the south. This wall was slightly inclined and rounded at the top, making the whole structure appear somewhat like a mastaba tomb.

Between the two entrances to the valley temple was a vestibule with walls of simple pink granite that were originally polished to a luster. Its floors were paved with white alabaster. A door then led to a T-shaped hall that made up a majority of the temple. This area too was sheathed with polished pink granite and paved with white alabaster, though it was also adorned with sixteen single block pink granite pillars, many of which are still in place today, that supported architrave blocks of the same material, bound together with copper bands in the form of a swallow’s tail. These in turn supported the roof.

Here, in the dim light provided by slits at the tops of the walls, stood as many as twenty four statues of the king (though one statue base in the middle that is larger than the others may have been counted twice) made from diorite, slate and alabaster. This line of statues continues along the cross of the T shaped hall ending at a doorway that leads to a corridor from which a stairway ramp winds clockwise up and over the top of the corridor before terminating on the roof of the valley temple.

On the south side of the roof was a small courtyard, situated directly over six storage chambers also built of pink granite and arranged in two stories of three units each. These were embedded in the core masonry of the T shaped hall. Symbolic conduits lined in alabaster, a material specifically identified with purification, run from the temple’s roof courtyard down into the deep, dark chambers below. These symbolic circuits run through the entire temple, taking in both the chthonic and the solar aspects of the afterlife beliefs and of the embalming ritual for which the valley temple was the stage, according to some Egyptologists.

Hence, the Polish scholar Bernhardt Grudseloff proposed that purification rituals were carried out on the roof terrace in a tent especially constructed for that purpose. Afterwards, he theorized that the body was embalmed in the temple antechamber.

A French Egyptologist, Etienne Drioton proposed a similar view, only switching the locations to the antechamber for the purification and the embalming on the roof terrace. However, Ricke correctly pointed out that these types of rituals required considerable water that was only available near the canal, so at best the priests of the valley temple could have only performed the rituals symbolically.

At the other end of the cross in the T shaped hall (north), an opening gave way to a pᴀssage, also paved with alabaster, that led to the northwest corner of the temple and there joined the causeway.