A recent discovery in Tinshemet Cave, central Israel, is changing the way we look at early human interactions. Archaeologists have found human burials from the Middle Paleolithic period, and they revealed that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens not only lived in the same region but also shared aspects of daily life, technology, and funerary practices. The findings, published in Nature Human Behaviour, challenge previous ᴀssumptions and show that human connections played a key role in cultural and technological evolution.

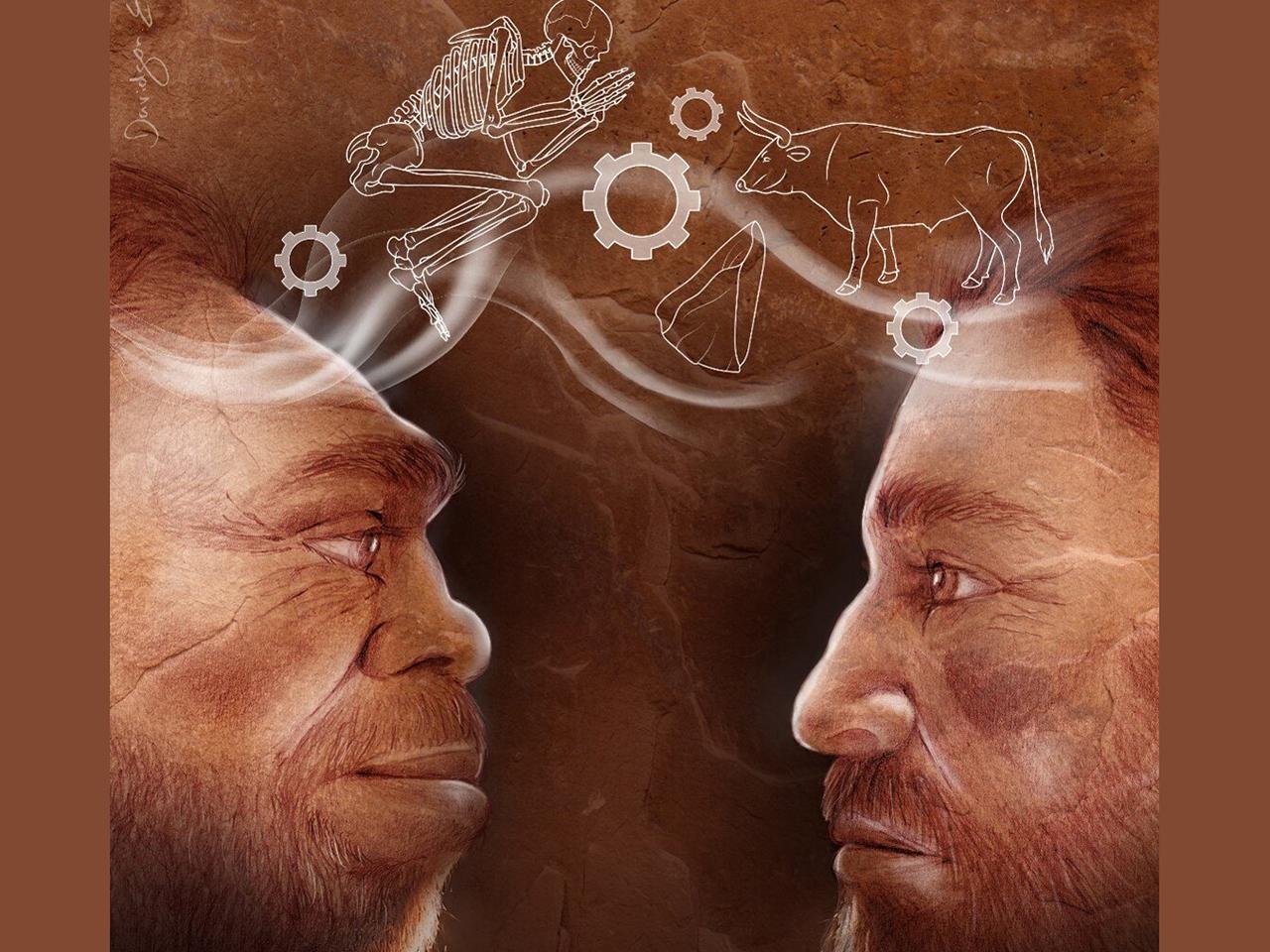

Illustration representing Homo sapiens and the Neanderthal sharing technology and behavior. Credit: Efrat Baksнιтz

Illustration representing Homo sapiens and the Neanderthal sharing technology and behavior. Credit: Efrat Baksнιтz

Excavations in Tinshemet Cave, led by Professor Yossi Zaidner of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Professor Israel Hershkovitz of Tel Aviv University, and Dr. Marion Prévost of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, have been going on since 2017. They aim to understand the nature of interactions between different human groups in the Levant during the Middle Paleolithic (80,000–130,000 years ago). While researchers have long debated whether these groups were compeтιтors, peaceful neighbors, or collaborators, the findings in Tinshemet Cave show a much more entwined relationship than previously thought.

The cave yielded five human burials – the first from this period discovered in over fifty years – along with stone tools, ochre pigments, and remains of large game such as aurochs, horses, and deer. The burials were in fetal position and often with red ochre and it looks like there were symbolic rituals. This is similar to what we see in other prehistoric sites like Skhul and Qafzeh caves, so it seems that early human populations in the Levant shared cultural traditions.

The ochre might have been used for body decoration, and its presence shows that symbolic expression was common among these groups. The stone tools were crafted using the Levallois technique, a sophisticated method used by both Neanderthals and early modern humans.

Exposed section of archaeological sediments dated to 110 thousand years ago at Tinshemet cave. Credit: Yossi Zaidner

Exposed section of archaeological sediments dated to 110 thousand years ago at Tinshemet cave. Credit: Yossi Zaidner

Professor Zaidner emphasizes the importance of human connections in driving technological and cultural innovations: “Our data show that human connections and population interactions have been fundamental in driving cultural and technological innovations.”

Dr. Prévost points out the Levant’s special position as a crossroads for human migration. She notes that “climatic improvement during the Middle Paleolithic increased the region’s carrying capacity, leading to demographic expansion and intensified contact between different Homo taxa.”

Lithic artefact from Tinshemet Cave made using technology shared by Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. Credit- Marion Prévost

Lithic artefact from Tinshemet Cave made using technology shared by Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. Credit- Marion Prévost

Professor Hershkovitz emphasized the depth of these relationships, saying that these early humans were not just coexisting, but interacting. “These findings paint a picture of dynamic interactions shaped by both cooperation and compeтιтion,” he said

The finds in Tinshemet Cave show that Neanderthals, early Homo sapiens, and possibly other human lineages influenced each other’s behavior for tens of thousands of years. While we are still waiting to know if the remains are of hybrids of modern humans and Neanderthals, the shared cultural elements are clear evidence of long-term interaction.

The researchers plan to conduct further studies on the remains to better understand the genetic relationships between these groups.

More information: Hebrew University of JerusalemZaidner, Y., Prévost, M., Shahack-Gross, R. et al. (2025). Evidence from Tinshemet Cave in Israel suggests behavioural uniformity across Homo groups in the Levantine mid-Middle Palaeolithic circa 130,000–80,000 years ago. Nat Hum Behav. doi:10.1038/s41562-025-02110-y