The frozen landscapes of Svalbard, a remote archipelago of Norway in the Arctic, have hidden a special archaeological find for years—graves from the 17th and 18th centuries that belong to European whalers. However, rising temperatures are fast becoming a menace to those very burial sites, accelerating their decay or even washing some into the sea.

Ancient whalers’ graves in Svalbard are vanishing as permafrost melts. Credit: Lise Loktu ©Sysselmesteren på Svalbard / NIKU

Ancient whalers’ graves in Svalbard are vanishing as permafrost melts. Credit: Lise Loktu ©Sysselmesteren på Svalbard / NIKU

The graves in Smeerenburgfjorden, Northwest Spitsbergen National Park, are among the oldest and most vulnerable cultural heritage sites in Svalbard. The graves, containing the remains of around 600 whalers, have been well preserved in permafrost for centuries. But climate change has begun to change the environment at an alarming rate, causing permafrost to thaw, destabilizing the graves, and exposing skeletal and textile materials to erosion and microbial decay.

Under the direction of Lise Loktu, an archaeologist and researcher at the Norwegian Insтιтute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU), the research project “Skeletons in the Closet” aims to document the damage and analyze the remains before they disappear. “The graves represent a unique archaeological resource that is rarely preserved elsewhere, neither in Europe nor the rest of the world,” Loktu explained.

In the last 30 to 40 years, there has been extensive climate change on Svalbard, with temperature increases leading to extreme weather, more precipitation, and intensified coastal erosion. As permafrost thaws, the active layer of soil also deepens with each pᴀssing year, making burial sites more vulnerable. Stronger wave action on the coast, coupled with reduced sea ice, accelerates the graves’ destruction.

Documentation of preserved skeletons and textiles from a grave that was examined at Likneset in 2019. Credit: Lise Loktu ©Sysselmesteren på Svalbard / NIKU

Documentation of preserved skeletons and textiles from a grave that was examined at Likneset in 2019. Credit: Lise Loktu ©Sysselmesteren på Svalbard / NIKU

“At Likneset, we have documented that many graves are being destroyed due to these climate-related changes,” Loktu said. “The coffins are collapsing, exposing skeletal and textile materials to sediment intrusion, water, and oxygen. Collectively, these processes accelerate the microbial decomposition of archaeological materials.”

The degradation is so rapid that researchers can observe noticeable changes from one year to the next. “We are in a race against time to document these graves before they disappear completely. There is still a lot of information to be gathered,” she added.

The remains of whalers buried in Svalbard are of immense value when it comes to learning about the lives of 17th- and 18th-century Europeans. From 1985 to 1990, excavations yielded a wealth of osteological data, which was analyzed by Elin T. Brødholt, an osteologist from the University of Oslo. These studies have shed light on the whalers’ health, living conditions, and social structures.

The analysis suggests that most of these people came from various European countries, including western Norway, where diets were very rich in marine food. Whalers, commonly ᴀssumed to be poor, actually exhibited evidence of social distinctions among them. For example, the average height of the individuals buried at Likneset was much greater than that of the people in other nearby cemeteries, an indication of better nutrition and economic conditions during childhood.

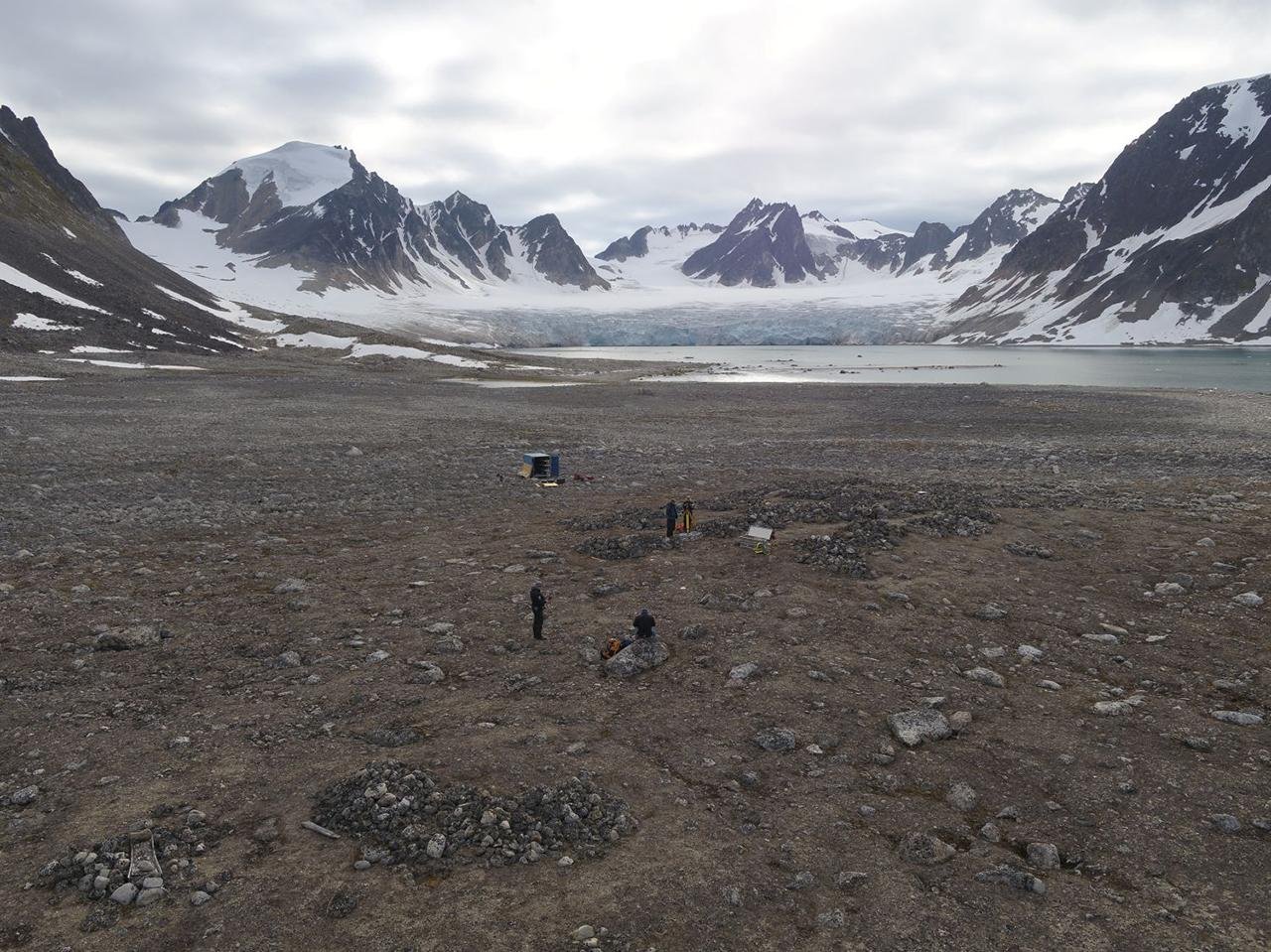

Researchers in the Skeletons in the Closet project are looking at the connection between climate change and increased degradation of these archaeological cultural environments. Credit: Espen Olsen ©Sysselmesteren på Svalbard

Researchers in the Skeletons in the Closet project are looking at the connection between climate change and increased degradation of these archaeological cultural environments. Credit: Espen Olsen ©Sysselmesteren på Svalbard

The skeletal remains point to the physically demanding life of whaling. Signs of malnutrition and disease were present in many whalers, and the leading cause of death was most likely scurvy, brought about by a deficiency of vitamin C.

Bone analysis also indicates that the majority of whalers engaged in strenuous labor from a very young age; the wear marks suggest extensive use of the upper body. Some of these changes resemble those seen in Inuit populations that used kayaks for hunting; hence, certain whalers likely had specialized roles such as paddling, rowing, or harpooning.

With graves breaking down more rapidly and some already being lost to the sea, researchers fear that critical historical knowledge could be washed away forever. Loktu noted: “The graves on Svalbard are now breaking down more rapidly and are gradually being washed into the sea due to erosion. This is about preserving knowledge that would otherwise disappear forever, knowledge that we cannot retrieve from anywhere else.”

The archaeologists are doing everything they can to preserve what remains before it is lost forever.