An archaeology team led by Hamza Benattia Melgarejo, a researcher from the University of Barcelona, proposes that their discovery of the remains of a settlement at Kach Kouch, along the Lau River, about 10 kilometers inland from the coast and 30 kilometers southeast of Tétouan, dating as far back as 2200 BCE, rewrites the current perspective of the environmental scenario of ancient Maghreb. This discovery challenges the long-held ᴀssumption that the region was virtually uninhabited until the arrival of the Phoenicians around 800 BCE.

Kach Kouch is located 10 kilometers from the present-day coast. Credit: Kach Kouch archaeological project / University of Barcelona

Kach Kouch is located 10 kilometers from the present-day coast. Credit: Kach Kouch archaeological project / University of Barcelona

In the study published in the journal Antiquity, Kach Kouch is presented as the oldest settlement of its kind in Mediterranean Africa outside of Egypt. The one-hectare site highlights three distinct phases of occupation, each representing a significant stage of establishment and adaptation.

The earliest phase of human activity at Kach Kouch, dated between 2200 and 2000 BCE, left behind limited but crucial evidence: three pottery sherds, a cow bone, and a chipped stone tool. Whether this phase saw a permanent settlement remains difficult to determine, but it confirms human presence in the region much earlier than previously thought.

A more established phase emerged from 1300 to 900 BCE when the site became home to a thriving agricultural community. Excavations revealed wood-and-mud-brick buildings, rock-cut silos, and stone-grinding tools indicative of a sedentary farming lifestyle. They cultivated barley, wheat, beans, and peas while rearing cattle, sheep, and goats. More than 8,000 animal bones were recovered from the site, reinforcing the picture of a self-sufficient community.

View of Kach Kouch and the Oued Laou estuary, looking east. Credit: H. Benattia et al., Antiquity (2025)

View of Kach Kouch and the Oued Laou estuary, looking east. Credit: H. Benattia et al., Antiquity (2025)

During the final occupation phase, spanning from 800 to 600 BCE, Phoenicians did not replace existing populations but instead influenced local culture and construction methods. Traditional wattle-and-daub houses, previously common, were now built on stone foundations, a characteristic of Phoenician architecture. This period also saw the introduction of wheel-thrown pottery and iron tools from the Mediterranean—a clear indication of increased cultural exchange.

“The excavations at this site reveal that the Maghreb was an active participant in the social, cultural, and economic networks of the Mediterranean,” said Benattia Melgarejo.

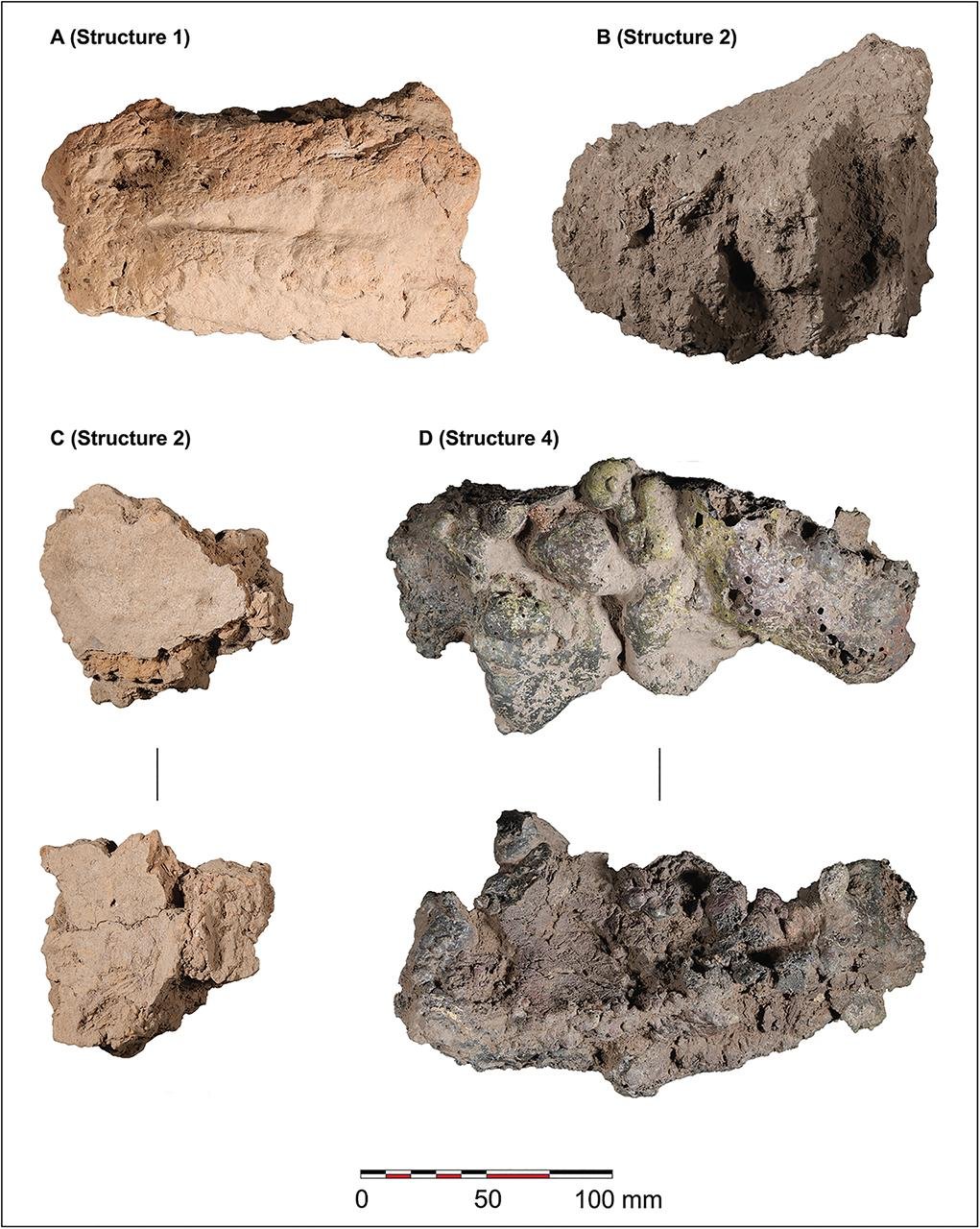

Daub fragments with imprints of wattle. Credit: P. Menéndez-Molist / H. Benattia et al., Antiquity (2025)

Daub fragments with imprints of wattle. Credit: P. Menéndez-Molist / H. Benattia et al., Antiquity (2025)

Despite the lack of extensive research projects focused on the region’s Bronze Age past, the findings from Kach Kouch provide convincing evidence that local communities engaged in agriculture, architecture, and trade before any external influence arrived.

Kach Kouch was abandoned around 600 BCE, with no signs of violence or destruction. The reasons remain uncertain, but researchers suggest that its inhabitants may have moved to newly established settlement sites along North Africa’s coastline, including Carthage, one of the Phoenicians’ most influential cities, which later clashed with Rome before its destruction in 146 BCE.

More information: University of Barcelona / Kach Kouch archaeological project

More information: Benattia, H., Bokbot, Y., Onrubia-Pintado, J., Benerradi, M., Bougariane, B., Bouhamidi, B., … Broodbank, C. (2025). Rethinking late prehistoric Mediterranean Africa: architecture, farming and materiality at Kach Kouch, Morocco. Antiquity, 1–21. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.10