A recent study has used advanced radiocarbon dating to present a more precise age for the Lapedo Child, a significant archaeological find that reshaped our perception of the interaction between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. The remains show both Neanderthal and modern human traits, and they have been dated to about 28,000 years ago, upending the earlier date range.

The Lapedo Child was first discovered in 1998 inside the Lagar Velho rock shelter in Lapedo Valley, Portugal. Credit: João Zilhão and Cidália Duarte / Bethan Linscott et al., Science Advances (2025)

The Lapedo Child was first discovered in 1998 inside the Lagar Velho rock shelter in Lapedo Valley, Portugal. Credit: João Zilhão and Cidália Duarte / Bethan Linscott et al., Science Advances (2025)

The Lapedo Child was first discovered in 1998 inside the Lagar Velho rock shelter in Lapedo Valley, Portugal. The remains belong to a four- to five-year-old child and were found in a burial site that initially hinted at a ritualistic context. The anatomical features of the skeleton, a blend of Neanderthal stockiness and modern human traits such as a prominent chin, quickly ignited discussions about interbreeding between these two human lineages. Hybridization, however, was a controversial proposition at the time, as the first Neanderthal genome had yet to be sequenced. However, later genetic studies confirmed that humans and Neanderthals interbred multiple times throughout history, leaving traces of Neanderthal DNA in modern non-African populations.

One of the persistent challenges in studying the Lapedo Child has been accurately dating the remains. Previously used methods of radiocarbon dating yielded broad and inconsistent results, ranging from 20,000 to 26,000 years BP. But a new study published in Science Advances has used a technique called compound-specific radiocarbon analysis (CSRA) to provide a more precise date range of 27,780 to 28,850 years ago. The method works chiefly by isolating specific amino acids from collagen in bones, rendering it very effective at removing modern contamination, which is problematic when dating poorly preserved remains.

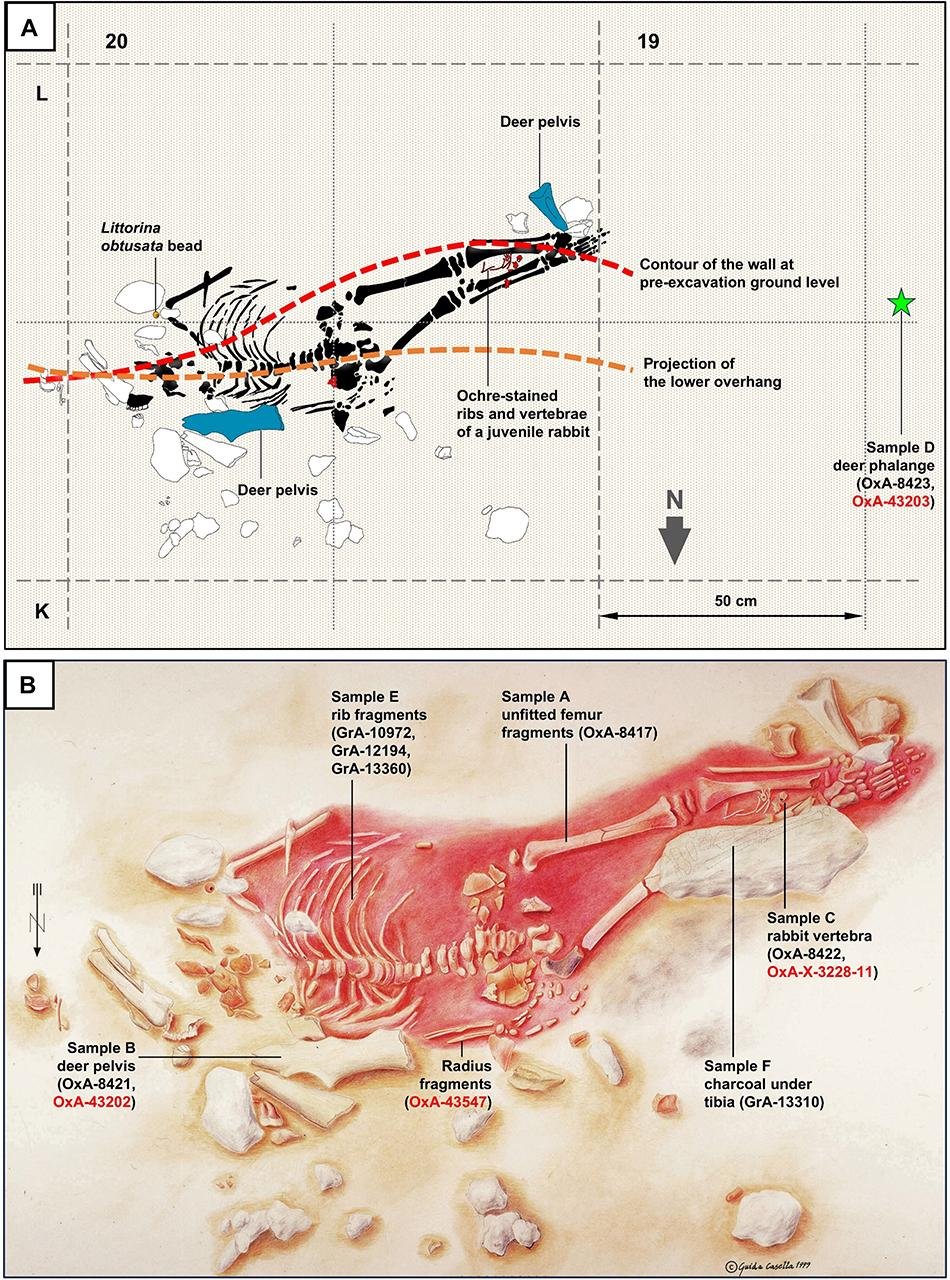

Apart from dating the skeleton itself, the researchers analyzed other materials found in the burial pit to determine whether they were part of a funerary ritual. They studied bones from a young rabbit, found atop the child’s remains, red deer bones located near the child’s shoulder, and charcoal beneath the legs, thought to be remnants of a ritual fire. The results revealed that while the rabbit bones were contemporaneous with the child, the red deer bones and charcoal were significantly older, indicating that they were not placed intentionally as part of a burial offering. Instead, the rabbit skeleton is believed to have been part of a symbolic offering before the grave was sealed, as it bears a red ocher pigment similar to that of the burial shroud.

Fragments of the child’s right radius, shattered in situ. Credit: Cidália Duarte / Bethan Linscott et al., Science Advances (2025)

Fragments of the child’s right radius, shattered in situ. Credit: Cidália Duarte / Bethan Linscott et al., Science Advances (2025)

Another striking conclusion from the study is the idea that the site was abandoned following the child’s burial. The child’s death might have led to the site being marked as taboo.

The abandonment of the site for over 2,000 years adds another layer to understanding burial practices and social behaviors. Prior research indicated cultural traditions surrounding death, both among early humans and Neanderthals, which this study reaffirms: that prehistoric communities, following major life events, may have ᴀssigned spiritual or symbolic value to certain locations.

Plan (A) and drawing (B) after (21). The position of the dated samples is indicated (the lab numbers in red are for their HYP redating). Artist Credit: (A) J.Z. and (B) G. Casella / Bethan Linscott et al., Science Advances (2025)

Plan (A) and drawing (B) after (21). The position of the dated samples is indicated (the lab numbers in red are for their HYP redating). Artist Credit: (A) J.Z. and (B) G. Casella / Bethan Linscott et al., Science Advances (2025)

The dating of the Lapedo Child thus expands the debate on the extent and duration of human-Neanderthal interactions. Genetic evidence suggests interbreeding began at least 49,000 years ago and continued for roughly 7,000 years. However, if the Lapedo Child, a hybrid individual, lived around 28,000 years ago, then questions arise as to whether genetic exchanges lasted longer than previously thought or whether hybrid traits appeared in later generations.

The study also highlights the potential for new dating techniques to improve our understanding of ancient human remains.

More information: Bethan Linscott et al. (2025). Direct hydroxyproline radiocarbon dating of the Lapedo child (Abrigo do Lagar Velho, Leiria, Portugal). Sci. Adv.11, eadp5769. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adp5769