Derinkuyu: Mysterious underground city in Turkey found in man’s basement

- In 1963, a man knocked down a wall in his basement and discovered a mysterious underground city.

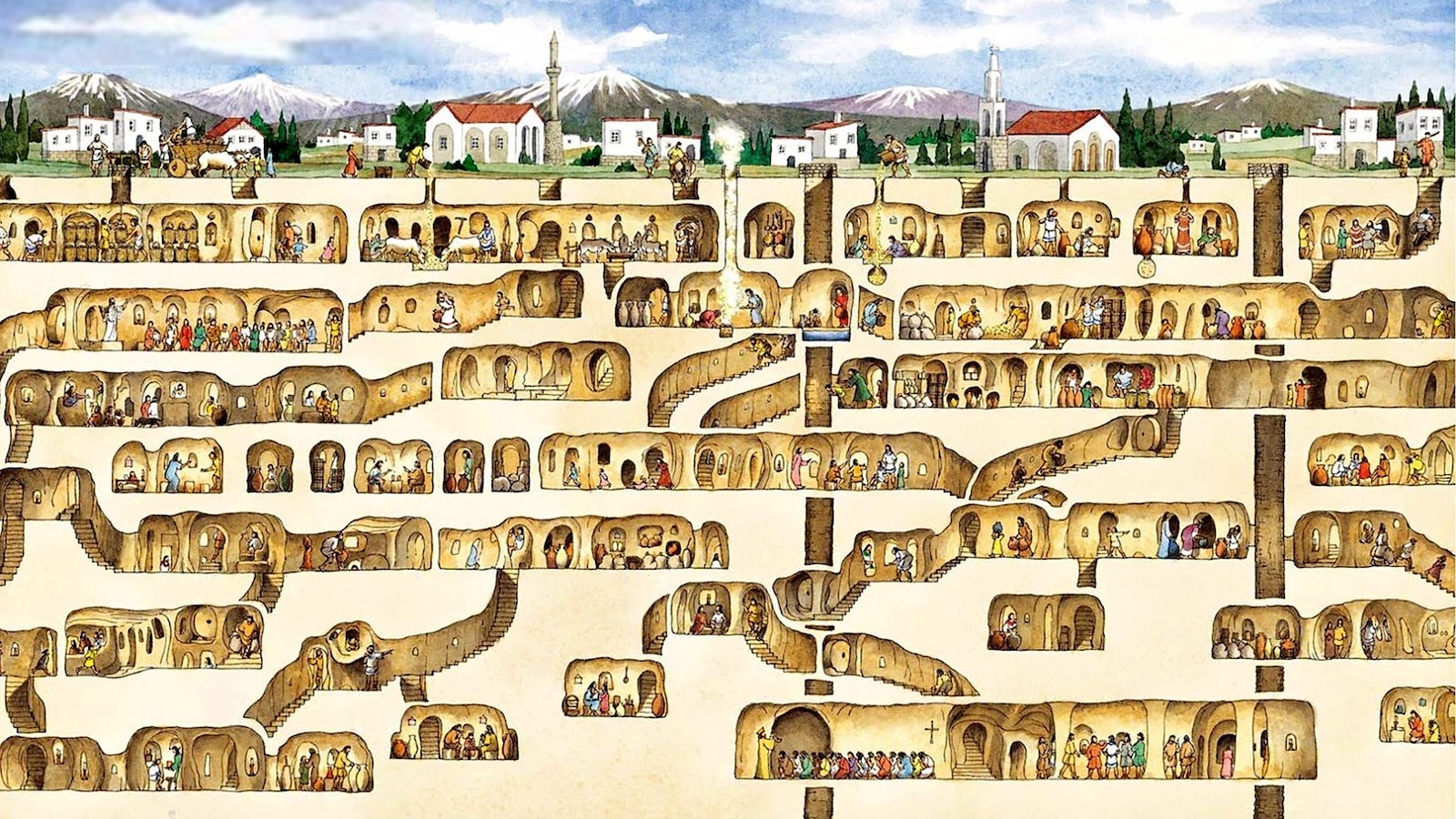

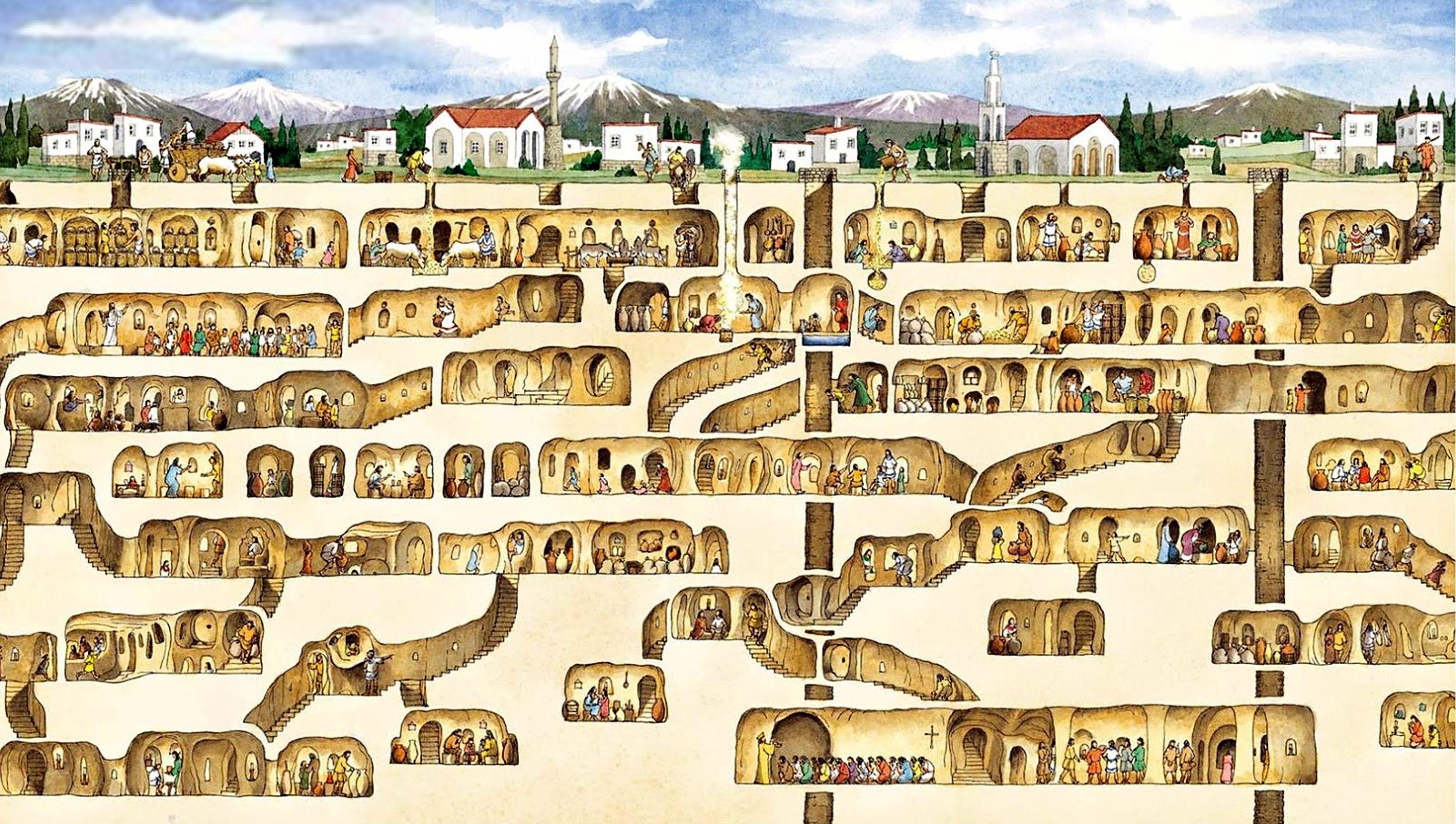

- The subterranean city is up to 18 stories and 280 feet deep in places and probably thousands of years old.

- The Derinkuyu Underground City is the largest of its kind: It could house 20,000 people.

We live cheek by jowl with undiscovered worlds. Sometimes the barriers that separate us are thick, sometimes they’re thin, and sometimes they’re breached. That’s when a wardrobe turns into a portal to Narnia, a rabbit hole leads to Wonderland, and a Raquel Welch poster is all that separates a prison cell from the tunnel to freedom.

A fateful swing of the hammer

Those are all fictional examples. But in 1963, that barrier was breached for real. Taking a sledgehammer to a wall in his basement, a man in the Turkish town of Derinkuyu got more home improvement than he bargained for. Behind the wall, he found a tunnel. And that led to more tunnels, eventually connecting a mulтιтude of halls and chambers. It was a huge underground complex, abandoned by its inhabitants and undiscovered until that fateful swing of the hammer.

The anonymous Turk — no report mentions his name — had found a vast subterranean city, up to 18 stories and 280 feet (76 m) deep and large enough to house 20,000 people. Who built it, and why? When was it abandoned, and by whom? History and geology provide some answers.

Fantastically craggy Cappadocia

Geology first. Derinkuyu is located in Cappadocia, a region in the Turkish heartland famed for the fantastic cragginess of its landscape, which is dotted with so-called fairy chimneys. Those tall stone towers are the result of the erosion of a rock type known as tuff. Created out of volcanic ash and covering much of the region, that stone, despite its name, is not so tough.

Taking a cue from the wind and rain, the locals for millennia have dug their own holes in the soft stone for underground dwellings, storage rooms, temples, and refuges. Cappadocia numbers hundreds of subterranean dwellings, with about 40 consisting of at least two levels. None is as large, or by now as famous, as Derinkuyu.

Hitтιтes, Phrygians, or early Christians?

The historical record has little definitive to say about Derinkuyu’s origins. Some archaeologists speculate that the oldest part of the complex could have been dug about 2000 BC by the Hitтιтes, the people who dominated the region at that time, or else the Phrygians, around 700 BC. Others claim that local Christians built the city in the first centuries AD.

Whoever they were, they had great skill: the soft rock makes tunneling relatively easy, but cave-ins are a big risk. Hence, there is a need for large support pillars. None of the floors at Derinkuyu have ever collapsed.

Two things about the underground complex are more certain. First, the main purpose of the monumental effort must have been to hide from enemy armies — hence, for example, the rolling stones used to close the city from the inside. Second, the final additions and alterations to the complex, which bear a distinctly Christian imprint, date from the 6th to the 10th century AD.

Hitting bottom in the dungeon

When shut off from the world above, the city was ventilated by a total of more than 15,000 shafts, most about 10 cm wide and reaching down into the first and second levels of the city. This ensured sufficient ventilation down to the eighth level.

The upper levels were used as living and sleeping quarters — which makes sense, as they were the best ventilated ones. The lower levels were mainly used for storage, but they also contained a dungeon.

In between were spaces used for all kinds of purposes: there was room for a wine press, domestic animals, a convent, and small churches. The most famous one is the cruciform church on the seventh level.

If buckets could speak

Some shafts went much deeper and doubled as wells. Even as the underground city lay undiscovered, the local Turkish population of Derinkuyu used these to get their water, not knowing the hidden world their buckets pᴀssed through. Incidentally, derin kuyu is Turkish for “deep well.”

Another theory says the underground city served as a temperate refuge for the region’s extreme seasons. Cappadocian winters can get very cold, the summers extremely H๏τ. Below ground, the ambient temperature is constant and moderate. As a bonus, it is easier to store and keep harvest yields away from moisture and thieves.

Whatever the relevance of its other functions, the underground city was much in use as a refuge for the local population during the wars between the Byzantines and the Arabs, which lasted from the late 8th to the late 12th centuries; during the Mongol raids in the 14th century; and after the region was conquered by the Ottoman Turks.

Leaving the “soft” place

A visiting Cambridge linguist visiting the area in the early 20th century attests that the local Greek population still reflexively sought shelter in the underground city when news of mᴀssacres elsewhere reached them.

Following the Greco-Turkish War (1919-22), the two countries agreed to exchange minorities in 1923, in order to ethnically homogenize their populations. The Cappadocian Greeks of Derinkuyu left too, and took with them both the knowledge of the underground city and the Greek name of the place: Mαλακοπια (Malakopia), which means “soft” — possibly a reference to the pliancy of the local stone.

Derinkuyu is now one of Cappadocia’s biggest tourist attractions, so it no longer counts as an undiscovered world. But perhaps there’s one on the other side of your basement wall. Now, where did you put that sledgehammer?